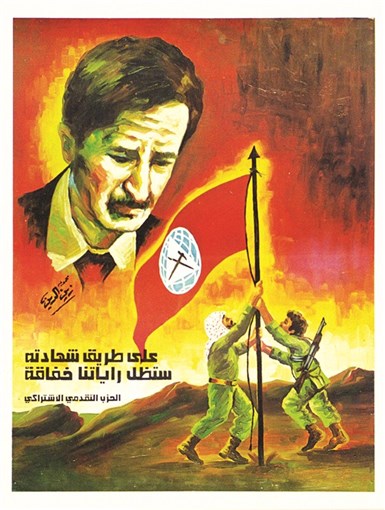

A look back at Kamal Jumblatt and the Progressive Socialist Party

Posted by Chris Solomon on Saturday, March 16th, 2019/Syria Comment Blog

https://www.joshualandis.com/blog/

The status of Syria’s Druze community has drifted in and out of the West’s attention during the long slog of the conflict. Talal el-Atrache’s recent article highlighted the precarious situation the Druze in Sweida Province, resting on the frontier of Da’esh, with the only option safeguarding their independence and security by way of the Syrian government. The brutal raid illustrated the fraught nature of civilians in southern Syria. Retaliation came quickly. Pictures circulated on social media showed a capture Da’esh fighter hanged from ruins of a Byzantine church over an arch known as “the gallows.” However, the Syrian Druze have also participated in the Syrian Civil War in organized fighting forces. Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi has highlighted the scope of the Druze Arab Unity Party and its affiliated militia, Saraya al-Tawheed, operations in Syria. In addition, Tamimi discussed the role Druze women have taken on by upon recruitment to pro-regime militias, such as Labawat al-Jabal.

Still, the position of the Syrian Druze throughout the war has been desperate, with some youth refusing to join the Syrian army. One young man told AFP in November, “The army is your grave.” Commentary and analysis has long pondered what the future holds in store for Syria’s Druze. Will they gain enhanced political influence or potential ostracization and persecution?

The Druze in wartime continues to be overshadowed by the Levant’s larger geopolitical events. For some insights into how the Druze transitioned from a combatant force into a peace time political entity, a look back at the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) and its militia, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), during the course of the Lebanese Civil War, yields some insights.

Founding of the Progressive Socialist Party to the 1958 Lebanon Crisis

Kamal Jumblatt was born in December 1917 to a powerful Druze family with Kurdish origins. His parents had a long history of protecting Druze interests in Lebanon. His father Fouad obtained an administrator post during the period of Ottoman rule. When Fouad was assassinated by a member of the rival Druze Arslan family in 1921, Kamal’s mother Nazira took over as the head of the Jumblatt family. Kamal traveled to France and obtained a degree in psychology and civil education at the Sorbonne University before returning to Lebanon in 1939. He took over as the head of the Jumblatt family in 1943, the year of Lebanon’s independence. He founded the Progressive Socialist Party (al-hizb al-taqadummi al-ishtiraki) in May 1949. The party was officially secular and had a Pan-Arab orientation. After Lebanon’s independence from France, Jumblatt formed a short-lived alliance with Camille Chamoun that brought down the corrupt and unpopular government of President Bechara El-Khoury in the Rosewater Revolution of September 1952.

However, with the Suez Crisis in 1956, regional tensions soon reverberated in Lebanon. Strong differences emerged between Jumblatt and Chamoun and the Druze leader turned towards Egyptian leader Gamal Abdul Nasser who had taken power in Cairo following the Free Officer’s coup in July 1952. Jumblatt strongly supported the Pan-Arabist movements in the region. When Syrian President Adib Shishakli arrived in Lebanon seeking a place of refuge after the anti-Shishakli National Front coalition (which included the Baath Party and Syrian Communists) overthrew him in a coup, Jumblatt’s threats forced the former Syrian strongman to leave for safety overseas in Brazil. This was largely in response to Shishakli’s brutal offensive against the Druze in February 1954.

By the late 1950s, the chasm between Lebanese President Camille Chamoun and Jumblatt reached a boiling point. In April 1957 Chamoun himself had voiced the opinion that reconciliation with Jumblatt was still possible.[i] However, a U.S. Embassy Beirut dispatch from August 1957 showed that the Druze leader had little trust or patience for his government. The dispatch relayed news of a meeting between Jumblatt and embassy staff where he denounced the Chamoun government and accused it of “gangsterism” in the Chouf and warned that his followers would take up arms to kick Chamoun’s “corrupt” local officials out of the area.

Jumblatt added that Lebanon’s internal situation was “deteriorating to the point where only a strong and respected leader like General Chehab could restore law and order to the country.” Furthermore, he believed that Lebanon “must put its own house in order” to meet the external threat posed by the Syrian-Soviet accord.[ii] By the end of that same month, Jumblatt, railed against the government’s arrest of his supporters, and told the Lebanese press that Chamoun was risking pushing the Druze into a “second Hermel,” a reference to the Druze uprising against the French colonial forces some 30 years prior. Defense Minister Majid Arslan, for his part, said, “I believe the law ought to be applied equally to everyone without discrimination as it has already been applied to my own brothers and friends.”[iii]

The Lebanese Civil War

Prior to the Lebanese Civil War, Jumblatt’s party went a period of renewal and strength. Despite the relative security under the Chehabist era, Lebanon was in the midst of social and political turmoil. From 1965 onward, the Druze-dominated movement had seen its membership increase from working class and the economically disenfranchised segments of Lebanese society, largely Druze and Shia, but also contained some Lebanese Sunni Muslims. It was in this climate that Jumblatt’s PSP had essentially positioned itself as an “agent of change.” In addition, the PSP also saw the Baath Party’s successful power grabs in Iraq and Syria and recognized the anti-imperialist sentiments popular in the region as a harbinger for Lebanon.[iv]

However, it was the alliance with the Palestinians that made the PSP the dominant power broker on the Lebanese left. In 1969, Jumblatt, in his role as Lebanon’s Interior Minister, legalized a group of radical leftist and nationalist political parties to allow them back into Lebanese politics. With the military might of the well-armed and politically assertive PLO fully behind it, Jumblatt’s PSP fastened itself in the conflict as the vanguard of the Lebanese National Movement (LNM). This coalition of largely leftist and revolutionary parties faced off against the Christian and conservative elements of the Lebanese political elite. A series of clashes, massacres and retaliations escalated into open warfare in April 1975. Although often described as a sectarian conflict, the Lebanese Civil War, at least in its early phases, had strong ideological undercurrents that transcended sect and ethnicity.

The PSP’s armed wing was known as the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Some sources put the total number of armed fighters in the PLA at 3,000.Although the party was staunchly secular, the PLA is typically described as one of the largest and most powerful sectarian armies in the civil war era. The militia is usually described as mainly composed of Druze and Shia recruits, with the latter effort occasionally put the PLA in conflict with the Amal militia of Imam Musa al-Sadr.[v]

After the LNM’s secured a series of victories against the Christian Lebanese Forces, Syria’s late President Hafez al-Assad grew wary of the rising power of the LNM, and feared it would threaten the integrity of the Lebanese state if the PLO was able to secure outright power on the Lebanese battlefield. He felt this would undermine Syria’s own influence in Lebanon and control over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In December 1975, Assad notified the Lebanese combatants that he would “strike anyone who broke the peace.”

Patrick Seale wrote that Jumblatt was “a genuine man of the left,” adding, “He had early befriended the Palestinians, proclaimed himself a Nasserist, enjoyed cordial relations with Moscow, and from the late 1960s onward had gathered together a vast constituency of Arab nationalists and radicals of all sorts. And by the spring of 1976, as his allies besieged the strongholds of his old Maronite rivals, he scented victory.”[vi] However, for Assad, this could not stand. In his view, the LMN was positioning Lebanon into a state of partition, which played directly into the geopolitical designs of Israel. After the Syrian military intervention in Lebanon in 1976, Jumblatt traveled to Damascus and endured a tense meeting with Assad. No agreement between the two was reached. Assad asserted that Jumblatt allegedly said he wanted to destroy the entire Lebanese confessional system. However, His son Walid later relayed that his father knew about Assad’s designs to divide the warring Lebanese factions and conquer Lebanon.

In early 1977, he traveled to Paris and met with French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. There he received promises of international support for Lebanon. Afterwards, he went to Cairo to hold court with Anwar Sadat, who had fallen out with Assad following the Arab’s defeat in the 1973 October War (Yom Kippur War). The Egyptian leader urged Jumblatt to stay in Cairo and allegedly warned him of an assassination plot.[vii]

Kamal Jumblatt was killed by unknown gunmen on March 16, 1977 while traveling to his home in Mukhtara. Apparently he had sought to establish his own autonomous administrative region in the Chouf. Jumblatt had been targeted for assassination earlier in December 1976 with a car bomb, which he accused the Syrian-backed Saiqa militia of being behind the attempt.[viii] Lebanese Communist Party leader George Hawi claimed in a 2005 interview that it was Assad’s brother, Rifaat al-Assad, who was responsible for the assassination.[ix] Others have suggested it was likely a botched kidnapping attempt. The exact details of Jumblatt’s assassination were never fully investigated by the Lebanese government and to this day, like many other crimes of the civil war era, the murder remains unsolved. However, there was a general consensus that the Syrian Air Force Intelligence was behind the incident.

Following Kamal Jumblatt’s death, Walid took over as the head of the PSP. The party and the civil war’s sectarian dimension became dramatically more distinct during this period. The Washington Post reported the cries of revenge by the Druze women at Jumblatt’s funeral, as well as the celebratory gunfire in the Christian sectors of East Beirut.[x] The impact of his death was felt particularly hard by the Palestinians. The Guardian quoted the late Yasser Arafat in 1977 saying, “It’s a tragedy. For us, Jumblatt was the equivalent of several armies fighting on our side.”[xi] The PSP engaged in brutal fighting with the Lebanese Forces in the so-called Mountain War from 1983-1984. The Lebanese Army joined with the Christian militias in an attempt to gain control over the predominantly Druze Chouf district.[xii] The PSP’s militia remained active in the conflict until the conclusion of the war, participating even in the final battles where the pro-Syrian forces routed General Michel Aoun’s troops holed up in the Baabda Palace during the so-called Liberation War. Aoun then left for his exile in France. Following the Taif Agreement, the PLA largely demobilized and entered the newly formed Lebanese Armed Forces and government security services. However, some elements of the PLA lingered on, participating in armed operations against the Israeli Defense Forces occupying southern Lebanon until the latter pulled out in 2000.

Nizar Hassan of the Lebanese Politics Podcast explained how Kamal Jumblatt’s life lingers on in Lebanese society 42 years after his assassination, “The essence of Kamal Jumblatt’s legacy on the PSP is that he represents the intellectual (and in a way spiritual) icon whose ideas and quality shall not be questioned. He is the figure to which all can pledge allegiance and about which they can express nostalgia. It is the hero that they never had ever since, a hero who is seen as a dreamer and visionary who carried the ideals of secularism, humanism and socialism, and beyond all a good and pure man. This is especially relevant because his son and successor Walid represents the other kind of qualities of the Za’eem; mainly political pragmatism and a focus on protecting the Druze and maximizing their share of social surplus. Another aspect of his legacy is the institutions that he created to ensure the party’s continuity and social dominance, which are arguably as powerful today as they ever were.”

Post-war politics

The fraught nature of commemorating Lebanon’s war martyrs was highlighted by Robert Fisk during the 40th anniversary of Kamal Jumblatt’s death. He noted that Walid has made every effort to warn against the bloody sectarian reprisals that followed his father’s assassination. Walid told Fisk in 2017, “He was trying to get rid of [Lebanon’s sectarian system] because the Muslims and Druze were not equal partners in the system. My father tried to do this peacefully. The elite of the Christians were with him. But the dream of a non-sectarian Lebanon was killed with him on the same day he died.”[xiii]

In 2005, Walid and the Lebanese Baath Party exchanged accusations over the death of PSP military official Anwar Fatayri, who was killed in 1989, after Walid had tasked him with pursuing reconciliation.[xiv]

Ultimately, Jumblatt ended up shunning the Syrians in the post-war period. After the 2005 assassination of Rafik Hariri, the PSP became a part of the anti-Syrian March 14th Alliance.

Nazih Richani, the author of Dilemmas of Democracy and Political Parties in Sectarian Societies: The Case of the Progressive Socialist Party of Lebanon 1949-1996, told Syria Comment Walid’s anti-Syrian positions were rooted in the assassination of his father, along with Rafik Hariri, and added, “Walid’s perception that Pax-Americana was eminent and that a ‘New Middle East’ was about to happen in the wake of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq. However, I think he miscalculated the geopolitical, regional, and global conditions and this drove him to the opposing camp of Syria.”

Walid’s son Taymour has taken over after the official head of the party. However, it is Walid who still retains control behind the scenes. Taymour has indicated to the press that he has a distain for the feudal brand of Lebanese politics.[xv]Nevertheless, the third generation of Jumblatts look set to continue on at the helm of the PSP. At a memorial commemorating Kamal’s 1977 assassination, Walid told Taymour, “Walk forward with your head held high, and carry the legacy of your grandfather.”[xvi]

Hassan touched on how the PSP had to reorganize in Lebanon’s post-war politics, “Unsurprisingly, the civil war gradually destroyed the ‘political party’ aspect of the PSP and empowered the sectarian militia character…[however,] the last few years have seen a conscious effort to resurrect the PSP as a fully functional political party (similar to what Samir Geagea did with the Lebanese Forces), as opposed to a one-man show. This is however is very unlikely to make any significant change as Taymour, Walid’s son who possesses none of the requirements for leadership, was handed the throne without any democratic process and in contrast with Walid’s insistence in the past that he is against ‘political inheritance’ and would encourage internal elections for new leadership.”

Still the PSP continues to be plagued with the lasting stigma of being a relic of the civil war’s sectarian character. One Syrian Social Nationalist named Elijah said, “Kamal Jumblatt was a man of principles and ideology, who did not sell himself to the highest bidder, as a Syrian Social Nationalist I respect that, even if I disagree with him.” He went on to lament the current state of the PSP, “For a party that is so progressive and socialist, they ended up representing Druze as only a sect, like most of the other Lebanese parties, and they are today a shallow image of what they used to be.”

Richani said, “Since 1977, in spite that the PSP’s ideology remains secular, conflict dynamics in a vertically divided society proved to be a formidable challenge. The secto-political system of representation that was engineered in the 19th century by colonial powers (France, the British, and the Ottomans) vying for influence was further reinforced by the French with the 1943 constitution. This in turn was consolidated with the Taif Accord of 1990. Certainly the objective conditions played a significant role in transforming the PSP into a predominatly sectarian-based group. But agency, like everything in history, played an equally important role.”

Hassan said, “The PSP today is a sectarian party that maintains social dominance through a variety of mechanisms, but most important is the clientelist relationship between supporters and the Jumblatt family. This has two dimensions: the resources offered directly in return for allegiance (such as jobs, healthcare support or material assistance) and the influence on the distribution of state’s resources (most importantly jobs, but also access to healthcare and bringing in state investments into the Druze areas). I can say that it is not individuals that support Jumblatt, it is the communities. The communities support Jumblatt and avoid any confrontation with him because they are worried about not being supported in the future. So the basis of support is largely material. On the other hand, there are the social-psychological aspects, such as the inherited sense of love and affiliation, the habitual involvement in PSP affiliated civil society organizations from young age, and the legacy of the civil war. The latter is also a major pillar of Jumblatt’s legitimacy: there is a perception that Walid Jumblatt offers protection for the Druze. He represents a well-connected, pragmatic, but also courageous figure that would pull strings to avoid harm, and if needed lead the violence when harm is inevitable.”

Following the Lebanese parliamentary elections in May 2018, the PSP engaged in violent clashes with its longtime Druze rival, the Lebanese Democratic Party (LDP). An office belonging to the PSP was bombed with an RPG, killed a local PSP volunteer and community activist named Alaa Abi Faraj. LDP head Talal Arslan was accused of harboring fugitive. The issue was later buried between the two sides.[xvii] However, the tension still exists between the PSP and LDP and most recently were manifested in a spat involving Sheikh Nasreddine Al Gharib, a pro-Damascus Lebanese Druze figure who did not approve the journey of Sheikh Naim Hassan, the head of the Druze Spiritual Council, who is aligned with Jumblatt. Subsequently, Sheikh Hassan was barred from entering Syria. Faour weighed in on the controversy, saying the move by the Syrian government was “further evidence of the return of the regime to its previous practices of intervention in internal Lebanese affairs.” The LDP defended Damascus. Its spokesperson Jad Haidar responded that Syrian sheikhs were required to obtain special identification for travel to Lebanon.[xviii]

Hassan said, “The LDP is incomparable to the PSP in size, power or ideological significance. It has no clear ideological tendency, no hero figure to give its current leadership legitimacy, and no major influence on the state’s resources. In the last election, the number of votes that the LDP leader Talal Arslan received was embarrassing to say the least; and if not for his inflation by the Free Patriotic Movement (an anti-Jumblatt strategy), he would have been largely insignificant on the national political scale. There is also quite a lot of hatred towards Arslan among the pro-Jumblatt communities for his support of the FPM’s major entrance into the politics of majority Druze areas in the last election, as he is seen to contribute to a political strategy that aims to weaken Jumblatt politically and revive sectarian tensions between the Christians and Druze of Mount Lebanon.” The PSP current has 2 cabinet positions in Lebanon’s newly formed government. Ayman Choucair, the State Minister for Human Rights Affairs, and has been in parliament since 1992. Choucair previously held other cabinet posts, including Ministry of Human Rights Affairs, Environment, and Agriculture. He was also the PSP’s director for the party’s office in Damascus from 1985 to 1991. During his time as the Minister of Human Rights Affairs, Choucair used his platform to pressure the Lebanese security forces over their treatment of the Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Following the deaths of four Syrian refugees in July 2017, he said, “To preserve the army’s image and prevent any rumors that may be malicious, we ask the relevant leadership and judiciary to open a transparent investigation into…the causes that led to the deaths.”[xix]

Another PSP member, Wuel Abu Faour, is the Industry Minister.[xx] He was previously the Minister of Health and was first elected to parliament in 2005. Faour lauded Russia’s role in securing the release of the Syrian Druze women who were taken captive by Da’esh in November 2018. He noted that Taymour played a role in working with the Russians on the situation. He said, “These recent events showed that Taymour Jumblatt’s confidence in the Russians was in place especially after the liberation operation. Further discussions about future arrangements related to the Druze’s situation in Syria are under way. A suggestion proposed that the Druze wanted for military service would join the fifth legion led directly by Russia, which is receiving positive feedback among Druze.”[xxi]

Faour suggested that the ties between Russia and the PSP were both long running and enduring. He explained, “The relation between [the PSP] led by Walid Jumblatt and the Russian Federation is historic. Russians preserve their relations with their historic allies and remember the great role of Kamal Jumblatt, who was awarded with the Order of Lenin among very few figures in the world. They also cherish the common friendship and struggle they share with Walid Jumblatt and want to consolidate the relation with his son Taymour.”[xxii]

Hassan shared his thoughts on Taymour’s future leadership of the PSP, “Taymour is far from a competent leader in any person’s mind, including the staunchest supporters of the Jumblatts. But the idea is that he is young and still learning, so we should give him a chance; this was the justification to support him in the 2018 election. It is hard to predict whether the PSP will continue to dominate druze politics in the future. On one hand, Taymour is a very pragmatic person when it is no longer civil war times and people need visionary change-makers. He does not represent any ideological standing, he does not have a particularly left wing or progressive rhetoric, and we have not seen any impressive leadership moments yet. But on the other, the PSP’s mechanisms of social control and dominance remain very strong, which makes it difficult to imagine how its influence could be declining anytime soon. The major variable to watch in the near future will be the rise of independent political movements in the Druze-majority areas (such as the group LiHaqqi), which is already influencing the PSP and pushing it in a left-progressive direction. This will either end in the PSP adopting the causes of these movements and preventing any potential loss of support to them, or the beginning of the end of feudal politics. The next decade will help us know what to expect.”

[i] U.S. Department of State, Embassy Beirut Telegram, April 11, 1957

[ii] U.S. Department of State, Embassy Beirut Telegram, August 27, 1957

[iii] U.S. Department of State, Embassy Beirut Telegram, August 28, 1957

[iv] Nazih Richani, Dilemmas of Democracy and Political Parties in Sectarian Societies: The Case of the Progressive Socialist Party of Lebanon 1949-1996, (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1998), p. 80-81

[v] Edgar O’Ballance, Civil War in Lebaon, 1975-1992, p. 16

[vi] Patrick Seale, Asad, The Struggle for the Middle East, p. 280-281

[vii] Saad Kiwan, Jumblatt’s legacy still echoes in today’s Lebanon, The New Arab, March 22, 2015, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/comment/2015/3/22/jumblatts-legacy-still-echoes-in-todays-lebanon

[viii] Edgar O’Bllance, Civil War in Lebanon, 1975-1992, p. 62

[ix] “George Hawi knew who killed Kamal Jumblatt,” Ya Libnan. June 22, 2005

[x] Stuart Auerbach, “Jumblatt Buried As His Followers Avenge Murder,” The Washington Post, March 18, 1977, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1977/03/18/jumblatt-buried-as-his-followers-avenge-murder/f858f618-bf32-4e25-b492-9d7043c4925b/?utm_term=.a5e308277118

[xi] “From the archive, 17 March 1977: Lebanese leftist leader Kamal Jumblatt assassinated,” The Guardian, March 17, 1977, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/17/lebanon-kamal-jumblatt-assassination-archive-1977

[xii] Nora Boustany, “Druze-Christian Fighting Spreads,” The Washington Post, December 13, 1984, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1984/12/13/druze-christian-fighting-spreads/5a88f929-51e0-4f81-ba4b-bd07176b8e57/?utm_term=.28811272bcff

[xiii] Robert Fisk, “On the 40th anniversary of Kamal Jumblatt’s death, is trouble brewing again in Lebanon?,” The Independent, March 19, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/lebanon-civil-war-walid-jumblatt-christianity-anniversary-a7638021.html

[xiv] Maher Zeineddine, “Jumblatt: Accusations of Fatayri murder aimed at hindering national reconciliation,” The Daily Star, February 14, 2005, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2005/Feb-14/2588-jumblatt-accusations-of-fatayri-murder-aimed-at-hindering-national-reconciliation.ashx

[xv] “Five new faces to follow in Lebanon’s parliament,” Agence France-Presse,

[xvi] “Lebanon’s Jumblatt affirms son Taymour as political heir,” Middle East Eye, March 19, 2017, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/lebanons-jumblatt-affirms-son-taymour-political-heir

[xvii] “1 killed in post-election clash in Lebanon town,” Xinhua News Agency, May 8, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-05/09/c_137164860.htm

[xviii] Sunniva Rose, “Syrian decision causes controversy among Lebanese Druze,” The National, March 4, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/syrian-decision-causes-controversy-among-lebanese-druze-1.833101

[xix] “Lebanon’s human rights minister calls for probe into Syrian deaths in custody,”Reuters, July 6, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lebanon-refugees-syria-minister-idUSKBN19R1FC

[xx] “Lebanon’s new Cabinet lineup,” The Daily Star, February 1, 2019

[xxi] “Lebanese MP: Sweida hostages were freed by Russia,” Arab News, November 12, 2018, http://www.arabnews.com/node/1403716/middle-east