The Taif turns 25

Khalil Gebara & Makram Rabah/Now Lebanon/6/11/2014

The 25th anniversary of the Taif agreement is yet another sad reminder of the schizophrenia of both the Lebanese people and their system.

It is safe to assume that the Lebanese are sentimentally attached to anniversaries, memorials and commemorations. In a pluralistic society with an assortment of religious and national occasions, the Lebanese enjoy plenty of holidays throughout the year. Chief among these is the annual 13 April remembrance of the 1975 outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War.

The public generally assumes that the civil war lasted for exactly 15 years and six months, ending on 13 October, 1990, with the removal of the renegade General Michael Aoun from the presidential palace in Baabda. However, it was almost a year prior to this date in the Saudi city of Taif that the countdown to the end of the civil war started.

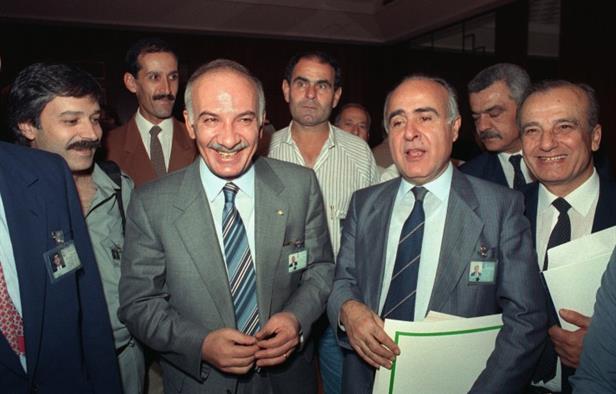

Sixty-two of the surviving 99 members of the 1972 parliament met to iron out and draft a national reconciliation document — commonly referred to as the Taif Accord — which was ratified two weeks later and incorporated into the Lebanese constitution.

The deliberations and deal making behind Taif were not entirely unique in their own sense. In this regard, the Taif agreement can best be described as a culmination of previous miscarriages to end the civil war, including the Constitutional Document of 1976, the Geneva and Lausanne Conferences of 1983 and 1984, the late PM Rashid Karami’s 1984 declaration and, finally, the short-lived Tripartite Agreement of 1985.

Recently, the Lebanese commemorated the 25th anniversary of the Taif Accord. Civil society organizations put together workshops and conferences, political talk shows hosted former parliamentarians, while commentators flooded daily newspapers with op-eds discussing the importance and continuing relevance of this agreement.

Conventional wisdom has it that the Taif Accord was never properly implemented. The Syrian regime, throughout its 15-year presence in Lebanon, derailed the implementation of many of the reforms approved by the 62 parliamentarians. The Syrian regime delayed the redeployment of its troops and did not facilitate crucial elements of the Accord, including the establishment of a senate, the abolition of political sectarianism and the launching of a comprehensive process of administrative decentralization.

However, it is difficult to imagine how Lebanon’s political system and constitutional institutions would function if the Taif agreement had been properly implemented. In this regard, many have argued that the amended constitution that incorporated many of the Taif agreement themes needs to be revisited in order to address ambiguities that affected the proper functioning of the institutions.

Proponents of this argument fail to realize that the Lebanese Constitution is designed to serve a power-sharing political system that rests on cooperation between the elites who, in turn, represent the interests of their communities. Any deadlock in this system, therefore, should not be simply resolved by looking to the constitution for proper and straightforward arbitration. Rather, it requires communal consultation and cooperation outside constitutional institutions.

Another issue that has been repeatedly raised is that the Taif constitution needs to be revisited so as to take into account changes in the balance of power and demographics between the various sectarian communities. The argument here is that the confessional parity that was introduced in the Taif agreement has expired and thus there is a need for a power-sharing formula. The main methodological problem with this argument is that it implies that the power-sharing formula should change continuously and be modified to reflect communal power on the ground. In other words, the power-sharing principal should be transformed from a constant to a variable.

On the 25th anniversary of the Taif agreement, it is safe to wonder whether an objective, constructive and practical debate on the Taif constitution is possible given the drastic regional changes and upheavals. The existential question remains, however, whether such a debate can be launched given the presence of a political and military entity – Hezbollah – that participates in the political system and its constitutional institutions, but at the same time has established its own independent political system with all its relevant symbols, such as an army, flag, socio-economic institutions, border management, as well as air and naval power.

Unfortunately, the 25th anniversary of the Taif agreement is yet another sad reminder of the schizophrenia of both the Lebanese people and their system, something which will surely survive for the next 25 years, if not beyond.

**Khalil Gebara is a Lecturer of Political Science at the American University of Beirut. Makram Rabah is a PhD candidate at Georgetown University’s History Department.