Arafat and the Ayatollahs

طوني بدران: عرفات والملالي

Tony Badran/Tablet/January 17/19

The PLO’s greatest single contribution to the Iranian Revolution was the formation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, but the Palestinian leader’s involvement with Iran didn’t end there

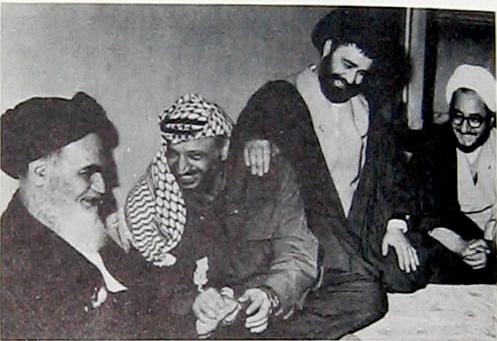

When Yasser Arafat arrived in Tehran on Feb. 17, 1979, the first “foreign leader” invited to visit Iran mere days after the victory of the revolution, he declared he was coming to his “own home.” There was some truth in Arafat’s flowery words. Having developed and nurtured a decade’s worth of relationships with all the major forces, from Marxists to Islamists, which had toppled the shah, he had good reason to feel like the victory of the revolution was in some part his own.

Although the heady days of February 1979 would soon give way to tensions, the Palestinians were integral to both the Islamic Revolution and to the formation of the Khomeinist regime. For Arafat, the revolutionary regime in Iran carried the promise of gaining a powerful new ally for the Palestinians. In addition, Arafat saw a chance to play the middleman between Iran and the Arabs, and to encourage them to eschew conflict with each other in favor of supporting the Palestinians in their fight against Israel. Yet it soon became clear that Arafat’s double fantasy was unattainable, and would in fact become quite dangerous to the Palestinian cause.

The relationship between the Iranian revolutionary factions and the Palestinians began in the late 1960s, in parallel with Arafat’s own rise in preeminence within the PLO. After the Iranian government crackdown of 1963, opposition groups resolved to adopt guerrilla tactics against the shah. By the end of the decade, Iranian opposition factions had made contact with Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) representatives in regional states including Qatar, and also Iraq, where Ayatollah Khomeini had been living since 1965. Marxist Iranian guerrilla organizations looking to receive training soon found their way to PLO camps in Jordan and South Yemen.

Yet after the defeat of the Arab armies in the 1967 war, and a string of PLO terror spectaculars made Arafat a media star, the PLO itself suffered a major military and political defeat in 1970, when it tried to take over Jordan. The Hashemite Kingdom then defeated and expelled Palestinian military organizations, in what became known as Black September.

One country afforded the defeated Palestinians the ability to operate freely under Arab cover, in the form of the Cairo Agreement of 1969. That country was Lebanon. Because the PLO’s position in the tiny country was unmatched anywhere else in the Arab world during the 1970s, Lebanon became the site where the major part of the Iranian revolutionaries’ encounter with the Palestinians played out.

Even before Lebanon’s own system collapsed, and the country plunged into civil war, fueled in part by Palestinian weapons and ambitions, the country had become a training ground for revolutionaries from all over the world, and a magnet for cadres of the main Iranian revolutionary factions, from Marxists to theocrats and everything in between. Leftist Palestinian groups, like the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), worked with Leftist Iranian factions, like the Marxist Fadaiyan-e Khalq and small Communist groups. Arafat’s Fatah organization worked with everyone. Coordinating these activities was Arafat’s right-hand man and Fatah’s chief military commander, Khalil al-Wazir, also known by his nom de guerre, Abu Jihad.

The number of guerrillas that trained in Lebanon with the Palestinians was not particularly large. But the Iranian cadres in Lebanon learned useful skills and procured weapons and equipment, which they smuggled back into Iran. A 1977 U.S. intelligence assessment noted the “quantity and sophistication of the weapons available to the terrorists,” which included “assault rifles, armor-piercing rifle grenades and possibly mortars, which allows them considerable flexibility in their tactics.” But guerrilla tactics carried out by Iranian leftist groups did not have any major success or even prominence in the revolutionary struggle within Iran before its very final phase. These tactics, however, would come into play in the transitional period following the collapse of the Pahlavi regime.

The three main Iranian opposition factions operating in Lebanon were: the Liberation Movement of Iran (LMI), often described as Islamic modernists; the Islamic-Marxist Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK); and the Islamist devotees of Ayatollah Khomeini. But the fact that the PLO worked with all of them didn’t mean that Arafat held them all in the same regard. The PLO did not develop any serious relationship with the LMI, for instance, which was aligned in Lebanon with the Iranian-Lebanese Shiite cleric Musa Sadr, who had fallen out with the Palestinians.

The PLO did establish close working ties with the Khomeinist faction. Three figures in particular from that camp were active in Lebanon, working closely with the PLO. Mohammad Saleh Hosseini, who was active in Iraq where he made contact with Fatah before coming to Lebanon in 1970; Jalaleddin Farsi, an Islamic activist and teacher who would run for president in 1980 as the Khomeinist faction’s candidate (before disclosure of his Afghan origin disqualified him); and Mohammad Montazeri, son of senior cleric Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri, and a militant who had a leading role in developing the idea of establishing the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps once the revolution was won.

The Lebanese terrorist and PLO operative Anis Naccache, who coordinated with these three Iranian revolutionaries, has given an account of the relationship. In it, he talks about his Khomeinist allies’ fear of a coup, after their victory, as the impetus behind the creation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—and he takes personal credit for the idea. Naccache claims that Jalaleddin Farsi approached him specifically and asked him directly to draft the plan to form the main pillar of the Khomeinist regime.

The formation of the IRGC may well be the greatest single contribution that the PLO made to the Iranian revolution. While it is also true that after the revolution, Montazeri asked Arafat to send Fatah fighters to Iran to directly train the new IRGC recruits, that effort did not see the light due to opposition from LMI figures in the provisional government. Reports of a massive Palestinian presence in Iran more generally would appear to be wildly overblown. While both the Palestinians and their enemies might fantasize about the PLO exerting a major independent influence inside Iran, there is no evidence that those fantasies ever approached fact.

The key battleground on which Palestinians and Iranians actually met was Lebanon. Khomeinist operatives in Lebanon were hostile to the LMI and their ally Musa Sadr, whose relationship with the Palestinians had turned antagonistic. The mutual hostility of Khomeinists and Palestinians towards Sadr led in 1978 to the Lebanese Shiite cleric’s murder in Libya—a country with whose leader, Muammar al-Qaddafi, the Khomeinists had established ties, with help from the Palestinians.

Arafat’s lieutenant, Ali Hassan Salameh, explained to the late CIA officer Robert Ames that Sadr was supposed to meet top Khomeini aide, Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, to iron out differences under Qaddafi’s auspices in Tripoli. Sadr arrived, but Beheshti never did. Instead, according to Salameh, Beheshti asked Qaddafi to detain Sadr, whom he described as a Western agent. More importantly, Beheshti would also characterize Sadr as “a threat to Khomeini.”

Back in Lebanon, Sadr’s circles pointed the finger specifically at Arafat allies, Jalaleddin Farsi and Mohammad Saleh Hosseini. According to these circles, Hosseini told an official from Sadr’s Amal movement, “your friend isn’t coming back.”

In addition to liquidating Sadr, Libya was an important source of funding for Khomeini as well as for the MEK. It also would prove to be a useful ally with the breakout of war between the newborn Islamic Republic and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which presented itself as the sword of the Arabs against the Persians and sought to crush its expansive-minded revolutionary neighbor.

The interfactional alliances and murderous rivalries that played out in Lebanon foreshadowed the power struggle that took place in the two-year transitional period following the triumph of the revolution, as the Khomeinists moved to consolidate their grip on power.

Arafat understood that the Khomeinists had the largest capacity for popular mobilization among the revolutionary forces inside Iran. But being Arafat, he always looked to keep multiple channels open while trying to leverage contradictory relationships. Following the revolution itself, he maintained his ties to the MEK, which in 1979-1981 was locked in a violent fight with the Khomeinist faction. That had now coalesced in the Islamic Republic Party (IRP), which dubbed itself Hezbollah, or the Party of God.

Hani Fahs, a Lebanese Shiite cleric who worked with Fatah as a liaison with the Iranians, explained that Arafat saw continuing his relationship with the MEK as a way to “poke” at the new Iranian regime if he wanted something or if he was upset at them. Shaking down Arab states was an established method for Arafat, one he thought he could replicate with Iran.

It’s also been noted that as the new Iranian regime launched operations to suppress the Kurdish insurgency in 1980, the defense minister at the time, Mostafa Chamran, who had spent time in Lebanon and was a close ally of Musa Sadr, recognized in the insurgency some of the same guerrilla tactics he saw the Palestinians and their allies use against Sadr’s Amal militia in Lebanon.

Yet Arafat’s continued ties to the MEK as it fought a bloody battle with the IRP, and his attempts to stick his nose in domestic Iranian affairs, did not amuse Khomeini, who had no patience for the Palestinian chief’s juggling act, and saw his actions as threats. Attempts by the PLO to overstep its boundaries within the Iranian political sphere were quickly shut down, in ways that were often not subtle.

Fahs relays a relevant anecdote of how he once offered his opinion during a conversation Mohammad Saleh Hosseini was having with Jalaleddin Farsi about Iranian foreign affairs, only to be put in his place by Hosseini, who curtly informed Fahs that he had no business weighing in on Iranian matters.

To be sure, Fahs was but a lowly apparatchik. Nevertheless, this attitude extended to Arafat himself, and to his lieutenants. In fact, as a 1980 CIA memo explained, PLO offices in Iran were closely monitored. The new regime would not allow Arafat and his Palestinians to become the tail that wagged the Khomeinist dog.

It wasn’t only Arafat’s attempt to play politics inside Iran that soured his relationship with Khomeini. From the get-go, Arafat also tried to cash in on his ties with the new regime by attempting to mediate the 444-day U.S. Embassy hostage crisis. Arafat’s meddling angered Khomeini, and further increased his suspicions of the Palestinian leader. When Arafat sent one of his top aides, Abu Walid (Saad Sayel), to Tehran to mediate, at the Americans’ request, Khomeini refused to receive him.

The Iraq-Iran war only deepened the PLO chairman’s predicament. Arafat could not side with Iran and condemn Iraq. That would risk losing the support of the Arabs, especially the wealthy Gulf states, which helped sponsor Saddam by paying him blackmail, and also provided the lion’s share of direct and indirect funding though bribes, payoffs, and remittances for the PLO’s own operations.

Again, Arafat tried to mediate. Khomeini, busy fighting a war in which half a million soldiers are estimated to have died, a majority of whom were Iranian, didn’t even bother to receive him this time. If Arafat thought he could ride two horses at once, balancing Iran against the Arabs, he was quickly disabused of that notion.

By the end of 1981, Arafat had very clearly lost favor in Tehran. To make things worse, two of his closest Iranian allies, Mohammad Montazeri and Mohammad Saleh Hosseini, would be assassinated that year—the former in an MEK bombing, the latter by Iraqi agents in Beirut. By then, the IRP had consolidated its grip on power within Iran and sidelined rival factions.

Likewise, within Lebanon, the dominant Iranian revolutionary faction—Hezbollah—had already begun cloning itself within its host country. Khomeini lieutenants like Hosseini had used connections with Fatah to recruit new cadres of Lebanese Shiite youth (among whom was a young man named Imad Mughniyeh) to their own banner. These recruits received military training in Fatah’s camps, but became part of a separate Khomeinist formation which was named after its Iranian progenitor.

In 1982, the PLO would be routed in Lebanon by the IDF, and was forced to withdraw its leadership under American protection to Tunis. By then the Iranians had already set up their own alternative structure to the PLO within Lebanon, formally known as Hezbollah.

Arafat would have one last dance with Iran before his death. After launching the Second Intifada against Israel, Arafat reached out to Iran for weapons. He purchased a freighter, the Karine A, in Lebanon, and the Iranians loaded it with 50 tons of weapons. Hezbollah commander Imad Mughniyeh played an integral role in the operation. The IDF intercepted the ship in January 2002.

Arafat’s fantasy of pulling the strings and balancing the Iranians and the Arabs in a grand anti-Israel camp of regional states never stood much of a chance. However, his wish to see Iran back the Palestinian armed struggle is now a fact, as Tehran has effectively become the principal, if not the only, sponsor of the Palestinian military option though its direct sponsorship of Islamic Jihad and its sustaining strategic and organizational ties with Hamas.

By forging ties with the Khomeinists, Arafat unwittingly helped to achieve the very opposite of his dream. Iran has turned the Palestinian factions into its proxies, and the PLO has been relegated to the regional sidelines.

https://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/278896/arafat-and-the-ayatollahs

حزب الله والحرس الثوري.. الانطلاقة كانت من معسكرات منظمة التحرير في لبنان، وعرفات اعتقد أنه يستطيع ركوب حصانين في آن وتحقيق التوازن بين إيران والعرب.

تقرير من اعداد طوني بدران/جريدة العرب/الأحد 2019/01/20

حزب الله والحرس الثوري.. الانطلاقة كانت من معسكرات منظمة التحرير في لبنان، وعرفات اعتقد أنه يستطيع ركوب حصانين في آن وتحقيق التوازن بين إيران والعرب.

قبلات مجانية

واشنطن – عند الحديث عن علاقة إيران بالقضية الفلسطينية، يطرح مباشرة ملف تبعية حركة حماس لإيران. لكن، لعلاقة اليوم جانب آخر منسي تأثيراته مازالت ماثلة بعد أربعين عاما من قيام الجمهورية الإسلامية في إيران التي كان لمنظمة التحرير الفلسطينية دور في تطور نظامها ودعم مؤسسها آية الله الخميني، وفي تشكيل الحرس الثوري الإيراني، كما في ترسيخ الدور الإيراني في لبنان منذ الحرب الأهلية.

يكشف عن البعض من هذه التفاصيل، التي ضاعت بين سطور الأجندة الإيرانية في المنطقة وما تتسبّب فيه من صراعات ومشاكل وفوضى، الباحث اللبناني طوني بدران في تحليل نشرته مؤسسة الدفاع عن الديمقراطيات، ضمن سلسلة لتغطية الذكرى الأربعين للثورة الإيرانية، وما أحيط بهذا الحدث المفصلي.

يركز التحليل على علاقة الزعيم الفلسطيني الراحل ياسر عرفات بالخميني، ويروي معلومات حول دعم حركة فتح للثورة الإيرانية، ودورها في تسليح الشيعة، وكيف أن حركة أمل وبعض قيادات حزب الله والحرس الثوري الإيراني هم “من خريجي” معسكرات التدريب التابعة لحركة فتح.

عندما وصل ياسر عرفات إلى طهران في 17 فبراير 1979، كأول “زعيم أجنبي” دُعي لزيارة إيران بعد أيام قليلة من انتصار الثورة الإسلامية. وصف عرفات هذه الزيارة بأنها بمثابة زيارة “بيته”. كان عرفات يضمر شيئا من وراء كلماته المنمّقة. فبعد أن أمضى عقدا في تطوير وتعزيز العلاقات مع جميع القوى الكبرى في ذلك الوقت، من الماركسيين إلى الإسلاميين، الذين أطاحوا بالشاه، أصبح لديه سبب وجيه للشعور بأن له دورا في انتصار الثورة.

خلال الأيام العصيبة التي شهدتها إيران بين سنة 1967 و1979، كان الفلسطينيون حاضرين. وكانوا جزءا من الثورة وساهموا في تشكيل نظام الخميني. بالنسبة لياسر عرفات، مثّل النظام الثوري في إيران فرصة لحصول الفلسطينيين على حليف قوي جديد.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، رأى عرفات فرصة للعب دور الوسيط بين إيران والعرب، وتشجيعهما على تجنّب الصراع مع بعضهما البعض، والعمل لصالح دعم كفاح الفلسطينيين ضد إسرائيل. ومع ذلك، سرعان ما أصبح من الواضح أن طموح عرفات غير قابل للتحقيق، وأنه سيصبح في الواقع خطرا على القضية الفلسطينية.

بدأت العلاقة بين الفصائل الثورية الإيرانية والفلسطينيين في أواخر الستينات بالتوازي مع صعود عرفات في صفوف منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية. في سنة 1963، وبعد حملة القمع التي شنتها الحكومة الإيرانية ضد المعارضة، قررت هذه الأخيرة اعتماد أساليب حرب العصابات ضد الشاه.

ومع نهاية العقد، تواصلت فصائل المعارضة الإيرانية مع ممثلي منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية في دول إقليمية بما فيها قطر وحتى العراق حيث كان آية الله الخميني يعيش منذ 1965. سرعان ما وجدت التنظيمات الماركسية الإيرانية طريقها إلى معسكرات منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية في الأردن وجنوب اليمن. بعد هزيمة الجيوش العربية في حرب 1967، جعلت سلسلة من عمليات منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية من عرفات نجما إعلاميا.

كانت ليبيا مصدرا مهما لتمويل الخميني ولحركة مجاهدي خلق. ثم أصبحت حليفا فاعلا مع اندلاع الحرب بين الجمهورية الإسلامية المولودة حديثا وصدام حسين، والذي قدم نفسه على أنه سيف العرب ضد الفرس، وسعى إلى سحق جارته الثورية

وعانت منظمة التحرير من هزيمة عسكرية وسياسية كبيرة في 1970، عندما تصادمت مع الجيش الأردني في الأردن. ثم طردت المنظمات العسكرية الفلسطينية، في ما أصبح يعرف باسم “أيلول الأسود”.

كان لبنان البلد الوحيد الذي قدم للفلسطينيين المهزومين القدرة على العمل بحرية تحت غطاء عربي، وتم ذلك من خلال اتفاق القاهرة سنة 1969. ولأن موقف منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية في هذا البلد الصغير لم يكن له مثيل في أي مكان آخر في العالم العربي خلال السبعينات، فقد أصبح لبنان الموقع الذي وقع فيه الجزء الأكبر من لقاءات الثوريين الإيرانيين مع الفلسطينيين.

حتى قبل انهيار نظام لبنان، واندلاع الحرب الأهلية، والتي تمت تغذيتها في جزء منها بالأسلحة والطموحات الفلسطينية، أصبحت البلاد ساحة تدريب للثوار من جميع أنحاء العالم، ومغناطيسا للكوادر من الفصائل الثورية الإيرانية، من الماركسيين إلى الثيوقراطيين وغيرهم.

عملت الجماعات اليسارية الفلسطينية، مثل الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين مع الفصائل الإيرانية اليسارية، مثل الفدائيين الماركسيين، من أمثال منظمة فدائيي خلق الإيرانية المسلحة، وأيضا تعاملت مع جماعات شيوعية صغيرة أخرى.

في المقابل، عملت حركة فتح مع الجميع. كان خليل الوزير، المعروف أيضا باسمه الحركي أبوجهاد، منسق هذه الأنشطة، وكان اليد اليمنى لياسر عرفات والقائد العسكري الرئيسي لحركة فتح.

لبنان همزة الوصل

لم يكن عدد المقاتلين الذين تدرّبوا في لبنان مع الفلسطينيين كبيرا. لكن الكوادر الإيرانية في لبنان تعلّمت مهارات مفيدة واشترت أسلحة ومعدات وهرّبتها إلى إيران. وأشار تقييم استخباراتي أميركي سنة 1977 إلى “كمية الأسلحة المتطورة المتاحة للإرهابيين”، والتي تضمنت “بنادق هجومية، وصواريخ خفيفة خارقة للدروع (أر.بي.جي)، وربما قذائف هاون، الأمر الذي يتيح لهم مرونة كبيرة في تكتيكاتهم”.

لكن تكتيكات حرب العصابات التي نفذتها الجماعات اليسارية الإيرانية لم يكن لها نجاح يذكر في النضال الثوري داخل إيران. لكن هذه التكتيكات ستلعب دورا في الفترة الانتقالية في أعقاب انهيار نظام الشاه رضا بهلوي.

كانت فصائل المعارضة الإيرانية الرئيسية الثلاثة العاملة في لبنان هي: حركة حرية إيران، التي غالبا ما توصف بأنها حداثية إسلامية؛ وحركة مجاهدي خلق الإيرانية؛ والإسلاميون المنقادون لآية الله الخميني. لكن عمل منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية مع جميعها لا يعني أن ياسر عرفات صنفها على نفس المستوى. لم تطور منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية أي علاقة جديّة مع حركة حرية إيران، حليفة الزعيم الديني الشيعي الإيراني-اللبناني موسى الصدر.

أقامت منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية علاقات عمل وثيقة مع الخميني. وكانت أهم ثلاث شخصيات نشطة في لبنان في تعاملها مع منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية هي محمد صالح الحسيني، الذي كان ناشطا في العراق حيث اتصل مع فتح قبل مجيئه إلى لبنان في 1970، وجلال الدين فارسي، وهو ناشط إسلامي ترشح للرئاسة في 1980 ضمن التيار التقليدي (قبل أن يستبعد بسبب أصله الأفغاني)، ومحمد منتظري، ابن رجل الدين البارز آية الله حسين علي منتظري، الذي كان له دور قيادي في تطوير فكرة إنشاء الحرس الثوري الإسلامي.

وقدم العضو في حركة التحرير الفلسطينية أنيس نقاش، الذي قام بالتنسيق مع هؤلاء الثوريين الإيرانيين الثلاثة، سردا لهذه العلاقة. وتحدث عن خوف حلفائه الخمينيين من انقلاب بعد فوزهم، كقوة دافعة لتأسيس فيلق الحرس الثوري. وقد تبنى الفكرة. وادّعى نقاش أن جلال الدين فارسي اتصل به، وطلب منه صياغة الخطة لتشكيل الدعامة الأساسية للنظام الخميني.

طوني بدران: من خلال إقامة علاقات مع الخمينيين، ساعد عرفات على تحقيق عكس حلمه. حوّلت إيران الفصائل الفلسطينية إلى وكلاء لها وحصرت منظمة التحرير في الهامش الإقليمي

طوني بدران: من خلال إقامة علاقات مع الخمينيين، ساعد عرفات على تحقيق عكس حلمه. حوّلت إيران الفصائل الفلسطينية إلى وكلاء لها وحصرت منظمة التحرير في الهامش الإقليمي

قد يكون تشكيل الحرس الثوري الإيراني أكبر مساهمة منفردة قدمتها منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية إلى الثورة الإيرانية. بعد الثورة، طلب منتظري من عرفات إرسال مقاتلي فتح إلى إيران لتدريب المجندين الجدد في الحرس الثوري، لكن ذلك لم يحدث بسبب معارضة أفراد من الحكومة المؤقتة.

بدت التقارير التي تشير إلى وجود فلسطيني كبير في إيران مبالغا فيها. في الوقت الذي قد يتخيل فيه الفلسطينيون، وأعداؤهم، نفوذا كبيرا لمنظمة التحرير الفلسطينية داخل إيران، لا يوجد دليل على حقيقة ذلك.

كان لبنان ساحة القتال الرئيسية التي التقى فيها الفلسطينيون والإيرانيون. كان النّشطاء الخمينيون في لبنان معادين لحركة حرية إيران وحليفهم موسى الصدر، الذي تحولت علاقته مع الفلسطينيين إلى عداوة. أدى العداء المتبادل بين الخمينيين والفلسطينيين مع الصدر في سنة 1978 إلى “مقتل” رجل الدين الشيعي اللبناني في ليبيا، وهي الدولة التي أقام الخمينيون علاقات مع زعيمها في ذلك الوقت معمر القذافي، بمساعدة من الأطراف الفلسطينية.

وأوضح مساعد عرفات علي حسن سلامة لضابط وكالة المخابرات المركزية روبرت أيمس، أنه كان من المفترض أن يلتقي الصدر مع آية الله محمد بهشتي، أحد كبار مساعدي الخميني، لتسوية الخلافات تحت رعاية القذافي في طرابلس. وصل الصدر، لكن بهشتي لم يأتِ. ووفقا لسلامة، طلب بهشتي من القذافي أن يحتجز الصدر، الذي وصفه بأنه عميل غربي و”تهديد للخميني”.

في لبنان، وجهت دوائر الصدر أصابع الاتهام إلى حلفاء عرفات، جلال الدين فارسي ومحمد صالح الحسيني. وفقا لهذه الدوائر، قال حسيني لمسؤول من حركة أمل “صديقك لن يعود”.

بالإضافة إلى دورها في تصفية الصدر، كانت ليبيا مصدرا مهما لتمويل الخميني ولحركة مجاهدي خلق في نفس الوقت. ثم أصبحت حليفا فاعلا مع اندلاع الحرب بين الجمهورية الإسلامية المولودة حديثا وصدّام حسين، والذي قدم نفسه على أنه سيف العرب ضد الفرس، وسعى إلى سحق جارته الثورية.

أدّت جملة التحالفات والتّنافسات القاتلة التي تشابكت في لبنان إلى نشوء صراع على السلطة في فترة انتقالية دامت سنتين بعد انتصار الثورة، حيث تحرك الخمينيون لتعزيز قبضتهم على السلطة.

فهم ياسر عرفات أن للخمينيين قدرة على التعبئة الشعبية بين القوى الثورية داخل إيران. لكنه كان يتطلع إلى إبقاء قنوات متعددة مفتوحة، أثناء محاولته الاستفادة من العلاقات المتناقضة. بعد الثورة نفسها، حافظ على صلاته مع حركة مجاهدي خلق، التي كانت تخوض معركة عنيفة مع فصائل الخميني بين 1979 و1981. وتجمّع ذلك في الحزب الجمهوري الإسلامي، الذي أطلق على نفسه اسم حزب الله.

وأوضح هاني فحص، وهو رجل دين شيعي لبناني عمل مع حركة فتح كحلقة وصل بينها وبين الإيرانيين، أن ياسر عرفات واصل علاقته مع مجاهدي خلق كوسيلة لـ“وخز” النظام الإيراني الجديد إذا أراد شيئا ما أو إذا كان مستاء منهم. كان هزّ الدول العربية أسلوبا راسخا عند ياسر عرفات، واعتقد أنه يمكن أن يتكرّر مع إيران.

قمع النظام الإيراني الجديد التمرّد الكردي في سنة 1980، ولاحظ وزير الدفاع آنذاك، مصطفى تشمران، الذي قضى بعض الوقت في لبنان وكان حليفا مقربا من موسى الصدر، أن نفس أساليب حرب العصابات التي استخدمها الفلسطينيون وحلفاؤهم ضد ميليشيا أمل في لبنان كانت حاضرة في مواجهة الأكراد.

ومع ذلك، فإن تواصل العلاقات بين ياسر عرفات ومجاهدي خلق في الوقت الذي يخوضون فيه معركة دامية مع الحزب الجمهوري الإسلامي، ومحاولاته التدخل في الشؤون الإيرانية الداخلية، لم يعجب الخميني الذي لم يكن راضيا على تصرفات الزعيم الفلسطيني ورأى فيها نوعا من التهديد. وسرعان ما تمّ صد محاولات منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية للتدخل في المجال السياسي الإيراني، بطرق واضحة.

ممنوع التدخل