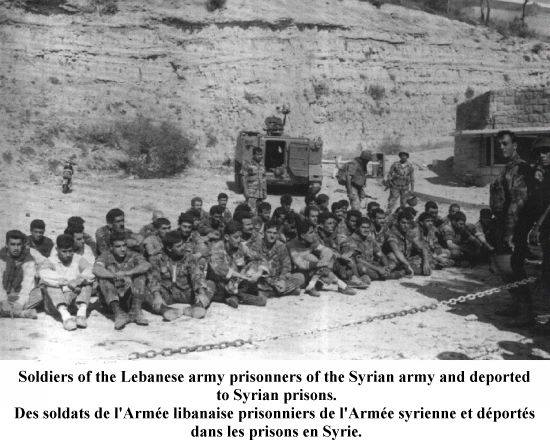

October 13, 1990

الدكتور وليد فارس وذكريات مؤلمة من واقعة 13 تشرين الأول 1990

Dr. Walid Phares/October 14/18

7 AM, Beit Mery, October 13, 1990. Sukhois flying over the Baabda district, bombing the Presidential palace. I can see them clearly from the balcony of the Del Sol Hotel, where I was staying. First thought that came to my mind: Assad got the green light from (US Secretary) Baker. It’s done, the attack is coming. Few minutes later, hundreds of artillery pieces opened fire from Beirut, Southern Suburb, Airport vicinity, Shuf, and Aley. Maybe from other areas. I saw this infernal concerto blasting, and the entire areas from Baabda to Broumana receiving thousands of shells. Scary, impressive and stressful. But as I discussed it with Dany Chamoun, Gebran Tueni and Prime Minister Aoun ad his cabinet, few days earlier, we knew it was to happen. The invasion was in the making.

Having lived the entire 15 years’ war in Lebanon and never left the mother land more than 15 to 20 days, one or two times, I had witnessed enough experiences to convinced me that even a large-scale military attack wouldn’t have taken half of the “East Beirut” defended by the Lebanese Army. For as we’ve seen in 1978, the Syrians were on the inside of Beirut and its suburbs, yet they failed, while facing few hundred fighters. The two Metns had a few Lebanese Army brigades, and a very supportive population.

Surely the Syrians would have progressed a little, and they did. But rapid counter attacks would have kept them out of balance. They were moving into hostile areas, with civilians fully opposed to them. The issue, the entire issue was about the leadership. Would the General fight or not? By 8:40 AM (more or less) we heard on the radio that the Prime Minister took refuge at the French embassy and surrendered the command of the Army to pro Syrian General Lahoud. The Lebanese Army is a regular force and unlike militias, obeys orders swiftly. Most of the fight ceased. The battle was lost politically, not militarily, so was the war.

What led to the disaster is part of forthcoming books, because it wasn’t fairly exposed to several generations in Lebanon. Some of the witnesses are no longer alive, others keep it for themselves, some are afraid of the truth, and a few prefer not to expose themselves to the inquiring public.

Around 730 AM I called Gebran Tueni whose house was at one kilometer from my hotel. He told me the clashes are around Deir el Qalaa, and that he is isolated. We tried to call Danny Chamoun but his line wasn’t answering. The question was: what should the population do? Gebran and Danny (I learned later) wanted to call Yarze and the Lebanese Front to continue the resistance. If the people would be mobilized to resist, the army would resume the resistance, they thought. Then there would negotiations. I learned later that officers wanted to continue the defense. As long as Yarze and Baabda were in good hands, the invasion would fail.

But the pro Syrian forces had prepared a comprehensive plan, including psychological warfare. Hundreds of phone calls targeted the Presidential palace, politicians, families of officers. The psy-op campaign aimed at achieving via intimidation what may not have been achieved on the ground.

I was told decades later, ironically by Syrian officers, who were part of the invasion and who later moved to the opposition, that even the Assad command wasn’t sure about the full success. They had learned a strong lesson in the summer of 1978. They feared being caught inside Ain Remmaneh, large villages facing a vast guerilla.

The night before the invasion I had called Rene Ala, the French ambassador with whom I had kept a close contact during the year. Ala informed me that there was coming, but the Lahoud forces and their Syrian allies were still waiting orders. He asked me what do I expect to happen. I told him “there are close to 700,000 inhabitants in the free areas (under Yarze control) and Army brigades.

If the attacks last longer, there would be more volunteers from the population to back the army. If the leadership knows what it is doing and keep calm through the storm.” I argued that even divided, the free areas can sustain the Assad attack. But France should take the matter to the UN Security Council immediately after a ceasefire. Ambassador Ala said this was possible and President Mitterrand was considering it. We had a longer conversation (to be cited in my memoirs later)

Confident that it will be a wild day, and even few more hot days, it will end with a ceasefire. It would have been a combination of a Souk el Gharb and an Ashrafieh 100 days war. Lebanese Army officers told ma later that they had the capacity of sustaining weeks of firm battlefield lines, and months of sporadic exchanges. All what was needed were a solid grip by the command and some international initiative. I knew that the latter was coming but I had no idea how Baabda would react.

I was not privy of the mass psychological campaign to take out the resolve of the Government. Then of course there was the question about the military and political position of the Lebanese Forces command. What would they have done had the Lebanese Army and the population resisted the Syrian Army for weeks? We’ll write about that later.

Reality was that by 9 AM, the Prime Minister surrendered, Yarze followed during the morning, the various units and the Maghawirs by the afternoon. By 4 PM, the last free enclave had fallen.

*Excerpts from Memoirs 1990)

*Image may contain: one or more people and outdoor