رئيس الحكومة اللبناني يستقيل، فماذا بعد؟

حنين غدار/معهد واشنطن/07 تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر 2017

في 4 تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر، استقال رئيس الحكومة اللبناني سعد الحريري بشكل غير متوقع، بإلقائه خطاب تلفزيوني من العاصمة السعودية، الرياض. وخلال الخطاب، ذكر مخطط اغتيال يحاك ضده واتهم إيران ووكلاءها بزعزعة استقرار بلاده والمنطقة الأوسع. وكان توقيت هذه الادعاءات مذهلاً بشكل خاص نظراً لأن الحريري كان قد استضاف للتو مستشار المرشد الأعلى الإيراني للشؤون الدولية علي أكبر ولايتي قبل يوم واحد، وأصدرا بعد الاجتماع بياناً مشتركاً سلّط الضوء على “مصالح لبنان”.

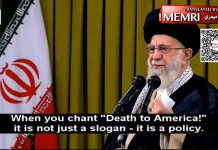

فضلاً عن ذلك، إن واقع حدوث الاستقالة في الرياض يحمل بعداً إقليمياً قد يجعل لبنان مفتوحاً أمام كل من الصراع الإيراني-السعودي والجهود الأمريكية الرامية إلى احتواء طموحات طهران في الشرق الأوسط – وقد تصاعدت حدة الصراع الإيراني-السعودي خلال نهاية الأسبوع بعد أن اعترض السعوديون صاروخاً أُطلق من اليمن باتجاه الرياض ووصفوه بأنه عمل حربي من قبل إيران. ولا يزال السبب الذي دفع بالحريري إلى إعلان استقالته في الرياض غير مؤكد. فربما يكون السعوديون قد ضغطوا عليه للقيام بذلك رداً على زيارة ولايتي، أو أنّ الاستقالة تأتي في إطار خطة أوسع نطاقاً لمواجهة «حزب الله» في لبنان. وفي السادس من تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر، تحدث وزير الخارجية السعودي عادل الجبير إلى شبكة “سي إن إن” بلهجة منذرة بسوء العاقبة، قائلاً إن الاعتداء على الرياض شمل “صاروخاً إيرانياً أطلقه «حزب الله» من أرض يحتلها الحوثيون في اليمن”. وبصرف النظر عن الحقيقة الكامنة وراء الاستقالة وحادثة الصاروخ، أصبح «حزب الله» أكثر تعرضاً الآن، من دون وجود حكومة ائتلافية تضفي طابع الشرعية على أنشطته المحلية والإقليمية، ومن دون شريك سني مهم ليحل محل الحريري.

وبدوره، انتقد زعيم «حزب الله» السيد حسن نصرالله هذه الاستقالة يوم الأحد، متهماً السعودية بإرغام الحريري على التنحي وإبقائه قيد الإقامة الجبرية. ولكن ما هو مهم أن خطابه جاء أكثر هدوءاً من المعتاد – فقد دعا عموماً إلى التروي وضبط النفس. ويبدو أن الاستقالة أخذت قادة «حزب الله» على حين غرة لأن الحريري لم يحاول تحدي سلطتهم منذ استلامه منصب رئاسة الوزراء مجدداً في العام الماضي. وعوضاً عن ذلك، تشير خطواته السابقة – مثل ترشيح حليف «حزب الله» ميشال عون لرئاسة الجهورية – وخطابه الأخير إلى أن خطته كانت تهدف إلى مواصلة التسوية مع الحزب.

أما بالنسبة لما سيحصل في المرحلة القادمة، فقد يتبلور واحد من عدّة سيناريوهات. فبموجب الدستور، من المفترض أن يدعو الرئيس عون إلى إجراء مشاورات نيابية لاختيار رئيس الوزراء المقبل. غير أنه وفقاً لتصريحاته الأخيرة، لن يقبل الاستقالة إلى حين حضور الحريري شخصياً إلى لبنان وشرح أسبابها، وهو ما طالب به السيد حسن نصرالله أيضاً. وإذا رفض الحريري ذلك، فقد يتعين على عون المضي قدماً لتسيير شؤون البلاد. وعلى أية حال، يواجه لبنان فراغاً خطيراً في مؤسساته. ونظراً إلى الوضع السياسي والأمني والاقتصادي الدقيق أساساً في البلاد، فإن المزيد من عدم الاستقرار قد يدفع بلبنان نحو مشاكل خطيرة.

وإذا لم يناسب الفراغ قادة «حزب الله» – الذين يدركون أنهم بحاجة إلى غطاء الحكومة لمواجهة عقوبات دولية جديدة محتملة – فقد يحاولون دفع الرئيس عون إلى استبدال الحريري برئيس وزراء آخر، علماً أن الدستور ينص على ضرورة أن يكون رئيس الوزراء من الطائفة السنية. غير أن هذا المسار سيكون زاخراً بالتحديات لسببين. أولاً، في الوقت الذي من المقرر فيه إجراء الانتخابات النيابية في أيار/مايو 2018 وتصاعد الضغوط الدولية على «حزب الله»، فإن أي زعيم سنّي سيواجه صعوبات سياسية للانضمام إلى حكومة يهيمن عليها «حزب الله». ثانياً، لا يملك الحزب النصاب اللازم في البرلمان الحالي لاختيار رئيس وزراء جديد – وفي الواقع، لا يملك أي فريق سياسي ما يكفي من المقاعد لتأمين هذا النصاب. ويخشى البعض من أن يلجأ «حزب الله» إلى تكتيك الاغتيالات لضمان النصاب القانوني. وبصرف النظر عمّا سيجري، ستكون الفترة الفاصلة شائكة.

أما بالنسبة للانتخابات نفسها، فقد كان الحصول على جميع الأطراف للاتفاق على التفاصيل كابوساً في الأساس، لذا فإن وضعهم الآن ضبابياً. فالفراغ الراهن يعزّز أكثر فأكثر ضرورة إجراء الانتخابات في موعدها، لكن استقالة الحريري – مع نبرة المواجهة التي اتسمت بها – قد تؤدي إلى تأجيلها أو ربما إلى ضغوط داخلية وخارجية لتغيير قانون الانتخاب النسبي الجديد. وكان الحريري قد وافق على هذا القانون لأنه ادّعى أن استقرار لبنان والعملية الديمقراطية لهما أهمية قصوى، على الرغم من الواقع بأن التغييرات الانتخابية من شأنها أن تضمن على الأرجح فوز «حزب الله» في أيار/مايو القادم من خلال منح حلفائه المزيد من المقاعد. والآن بعد أن تبدلت أولويات الحريري على ما يبدو، فإن القانون الجديد والجدول الزمني للانتخابات لم يعُدا مؤكدين.

وقد تؤثّر استقالته أيضاً على عدد كبير من البنود التي مررتها الحكومة، بما فيها مراسيم النفط والغاز للتنقيب بحراً عن هذه الموارد والميزانية الوطنية الجديدة، التي تعد الأولى من نوعها فى لبنان منذ اثني عشر عاماً. وقد تؤدي الاضطرابات الناتجة إلى إبعاد الشركات الأجنبية التي تحتاج إلى الثقة في البيئة السياسية من أجل الاستثمار في الأعمال التجارية – وهو احتمال قاتم نظراً إلى أن لبنان لا يزال يعاني من تداعيات الحرب السورية التي قطعت طرقاً تجارية رئيسية وأسفرت عن تدفق أكثر من مليون لاجئ إلى لبنان.

وتعني هذه المشاكل، إلى جانب احتمال تدخل السعودية وإيران بشكل أقوى، أن شبح الأزمة السياسية والاقتصادية يقترب بوتيرة أسرع حتى من لبنان. وبناء على ذلك، يجب أن يستجيب المجتمع الدولي لهذه الاستقالة من خلال وضع خطة منسقة ترمي إلى تحقيق هدفين هما: ضمان استقرار البلاد، ومواجهة «حزب الله» للحرص على عدم استغلاله هذا الفراغ.

وسواء اختار «حزب الله» قبول الفراغ إلى حين إجراء الانتخابات أم لا، فسيبذل قصارى جهده لمواصلة السيطرة على لبنان وسط التحديات الإقليمية والمحلية المتنامية، الأمر الذي يمنح خصومه المحليين والخارجيين فرصة التصدي له، ولا سيما على خلفية الانتخابات المقبلة. وقد يكون دعم المرشحين المناهضين لـ«حزب الله» أو السعي إلى تغيير القانون الانتخابي خطوتين مفيدتين في هذا الشأن. لكن من غير المحتمل إجراء الانتخابات في موعدها ما لم يساعد المجتمع الدولي لبنان على عدم الانجرار إلى الفوضى ويضمن عدم تصعيد الحرب الإيرانية-السعودية وتحويلها إلى اشتباكات مسلحة داخل لبنان. إن الفراغ السياسي والفوضى لم يساهما سوى في تقوية «حزب الله» وإضعاف الدولة منذ عام 2005، ولذلك لا يمكن التعويل عليهما بالفعل لمواجهة الحزب اليوم.

حنين غدار، صحفية وباحثة لبنانية مخضرمة، وزميلة زائرة في زمالة “فريدمان” في معهد واشنطن.

Lebanon’s Prime Minister Resigns: What’s Next?

Hanin Ghaddar/The Washington Institute./November 07/17

Hariri’s announcement could make Hezbollah and its Iranian patron more vulnerable to international pressure, particularly if the upcoming parliamentary elections do not go their way.

On November 4, Lebanese prime minister Saad Hariri unexpectedly resigned during televised remarks delivered in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The speech mentioned an assassination plot against him and accused Iran and its proxies of destabilizing his country and the wider region. The timing of these claims was especially startling given that Hariri had just hosted Ali Akbar Velayati, the Iranian Supreme Leader’s advisor for international affairs, one day prior, after which they released a joint statement emphasizing the “interests for Lebanon.”

Moreover, the fact that the resignation happened in Riyadh carries a regional dimension that could open Lebanon up to both the Iranian-Saudi conflict — which escalated this weekend after the Saudis intercepted a missile fired on Riyadh from Yemen and characterized it as an act of war by Iran — and U.S. efforts to contain Tehran’s ambitions in the Middle East. It is still uncertain why Hariri made the announcement in the kingdom. The Saudis may have pressured him to do so in reaction to Velayati’s visit or as part of a wider plan to confront Hezbollah in Lebanon. Earlier today, Saudi foreign minister Adel al-Jubeir struck an ominous tone, telling CNN that the attack on Riyadh involved “an Iranian missile, launched by Hezbollah, from territory occupied by the Houthis in Yemen.” Whatever the truth behind the resignation and the missile incident, Hezbollah is now more exposed, without a coalition government to give its domestic and regional activities the stamp of legitimacy, and without a substantial Sunni partner to replace Hariri.

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah criticized the resignation on Sunday, accusing Saudi Arabia of forcing Hariri to step down and keeping him under house arrest. Significantly, though, his rhetoric was calmer than usual — he mostly called for patience and restraint. Hezbollah leaders seemed taken aback by the resignation, as Hariri has not tried to defy their authority since he came back as prime minister last year. Rather, his prior moves — such as nominating Hezbollah ally Michel Aoun for the presidency — and recent rhetoric signaled that his plan was to keep compromising with the group.

As for what happens next, one of several scenarios could unfold. Under the constitution, President Aoun is supposed to call for parliamentary consultations to pick the next premier. According to his most recent statements, however, he will not accept the resignation until Hariri returns to Lebanon and explains his reasons, something that Nasrallah demanded as well. If Hariri refuses, Aoun may have to move on. In any case, Lebanon faces a serious void in its institutions. Given its already delicate political, security, and economic situation, more instability could push the country into serious trouble.

If the void does not suit Hezbollah leaders — who know they will need the cover of government to face potential new international sanctions — they could try to push the president to replace Hariri with another premier, who is constitutionally required to be a Sunni. Yet this route would be challenging for two reasons. First, with parliamentary elections slated for May 2018 and international pressure on Hezbollah escalating, any Sunni leader would find it politically difficult to join a Hezbollah government. Second, the group does not have the necessary quorum in the current parliament to choose a new prime minister — in fact, no party does. Some fear that Hezbollah will resort to assassinations in order to secure the quorum. Whatever happens, the interregnum will be thorny.

As for the elections themselves, getting all factions to agree on the details was already a nightmare, so their status is now up in the air. The current void makes it even more urgent to hold the elections on time, but Hariri’s resignation — with the confrontational tone it embodied — might lead to a postponement, or perhaps internal and external pressure to change the new proportional electoral law. Hariri agreed to that law because he claimed that Lebanon’s stability and democratic process were paramount, despite the fact that the electoral changes would probably guarantee Hezbollah’s victory next May by allowing its allies more seats. Now that Hariri’s priorities have seemingly shifted, the new law and election schedule are no longer certain.

His resignation might also affect several items passed by his cabinet, including oil and gas decrees for offshore exploration and the new national budget, Lebanon’s first in twelve years. The resultant turmoil could scare off foreign companies that need to trust the political environment in order to make business investments — a grim prospect given that Lebanon is still struggling with the impact of the Syria war, which cut major trade routes and brought more than one million refugees into the country.

These problems, coupled with the possibility of more forceful interference by Saudi Arabia and Iran, mean that Lebanon could move even faster toward political and economic crisis. Accordingly, the international community should respond to the resignation with a coordinated plan aimed at two goals: ensuring the country’s stability, and confronting Hezbollah to make sure it cannot use the void to its advantage.

Whether or not Hezbollah choses to accept the void until elections, it will try its best to keep a grip on Lebanon amid growing regional and domestic challenges. This gives its domestic and foreign opponents an opportunity to push back, particularly against the backdrop of upcoming elections. Supporting anti-Hezbollah candidates or pushing to change the electoral law could both prove helpful. But elections are unlikely to be held on time unless the international community keeps the country from succumbing to chaos and ensures that the Iran-Saudi war does not escalate into armed clashes inside Lebanon. Political voids and chaos have only strengthened Hezbollah and weakened the state since 2005, so they are hardly a recipe for countering the group today.

**Hanin Ghaddar, a veteran Lebanese journalist and researcher, is the Friedmann Visiting Fellow at The Washington Institute.