Why Islamists (Occasionally) Desecrate Islamic Holy Sites

Tarek Fatah/The Toronto Sun/July 5, 2016

Originally published under the title “The Historical Roots of Islamist Terrorism.”

People stand by the site of a suicide bombing in Medina, Saudi Arabia, on July 4.

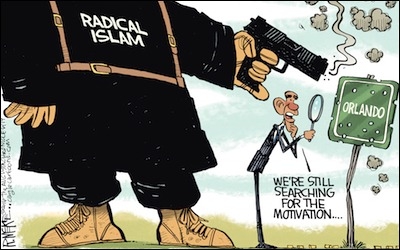

Monday’s suicide bombing outside the tomb of Prophet Muhammad in Medina, Saudi Arabia, sent shock waves throughout the Islamic world. The fact a Muslim carried out this act of terror during the holy month of Ramadan has left many followers of the Islamic faith in disbelief.

Too many Muslims have fallen for the common refrain, trumpeted by Islamists, that no Muslim could carry out such an act and hence neither Islam nor Muslims can be held accountable for it in any way.

These arguments have been used every time Islamist terrorists engage in mass killings, from 9/11 in New York to the massacre in Dhaka, Bangladesh, last week. But the facts tell us a different story regarding the turbulent history of Islam and the roles played by Muslims within it.

Academics and scholars are reluctant to discuss these historical facts for fear of being accused of bigotry and racism. Thus ordinary Muslims, to say nothing of non-Muslims, do not commonly know them.

The result is a Muslim community unaware of its own often bloody history, going back centuries, when both our holy cities — Mecca and Medina — were attacked, ransacked and destroyed, not by the “kufaar” (non-Muslims), but by Muslim leaders.

Militant Islamists have seldom hesitated to desecrate Islamic holy sites.

They fought for power, using Islam as a tool to enhance or entrench their political hold on the states they created.

Fanatical, politically motivated, and radicalized Muslims have never hesitated to desecrate Islam’s holy sites.

As early as October, 683 AD, the Umayyad caliph of Damascus invaded Mecca, then under the control of a rival caliph, and bombarded the ancient shrine of Black Kaaba, the holiest site in Islam.

The Kaaba, where Muhammad preached, was destroyed in the fighting. A new one was constructed.

Skipping over the centuries, we have the 1805 invasion of the Prophet’s city, Medina, by the first Saudi state.

Imbibed with a fierce zealotry, the Wahhabi warriors of Muhammad Ibn Saud overran Medina and started to destroy Islamic shrines. They even tried to destroy the magnificent dome structure over the tomb of Prophet Muhammad, removed all precious objects from his gravesite and looted the treasury of the mosque itself.

After occupying Medina these Muslims, who came from the neighbouring region of Nejd, systematically leveled the “Jannat al-Baqi” cemetery, the vast burial site adjacent to the Prophet’s mosque that housed the remains of many of the members of Muhammad’s family, close companions and central figures of early Islam, including his beloved daughter, Fatima.

These acts of sacrilege were re-enacted by a new generation of Wahabbi zealots led by Abdel-Aziz Ibn Saud during the second Saudi state, a century later.

Juhayman al-Otaybi after his capture.

On April 21, 1925 the rebuilt tombs and domes in Medina were once again bulldozed. Had it not been for intervention and diplomacy by then Prince Faisal (later King), who was in command of the regular Saudi army, the Wahabbis would have destroyed Prophet Muhammad’s tomb as well.

As recently as November 1979, radicalized Muslims from around the world, including the U.S., Pakistan and Egypt, led by Saudi fanatic Juhayman al-Otaybi, took over the Holy Kaaba and killed many people during a two-week siege.

The moral of the story is that no matter how often Muslims refuse to acknowledge our history, it will not hide the mess we have created that we now refuse to cleanse.

Let us own up to it and stop blaming others for it.

**Tarek Fatah, a founder of the Muslim Canadian Congress and columnist at the Toronto Sun, is a Robert J. and Abby B. Levine Fellow at the Middle East Forum.

Religious Intolerance in the Gulf States

Dateline

Hilal Khashan/Middle East Forum/July 06/16

Middle East Quarterly

There are now more than three and a half million expatriate Christians working in the six Gulf Cooperation Council states, mostly Catholics from the Philippines, India, and Pakistan.

Interest in the state of Middle East Christians has largely focused on the quality of their lives in the Levant, Egypt, and Southern Sudan, predominantly Christian areas before the rise of Islam that still contain sizeable Christian minorities. By contrast, little attention has been paid to Christians in the Arabian Peninsula, which had no indigenous Christian presence in Islamic times.

However, the oil boom of the 1970s created a tremendous demand for foreign labor in the Persian Gulf rentier states. Unsurprisingly, the number of workers needed to drive the emerging economies of the Gulf states was bound to include significant numbers of Christians. There are now more than three and a half million expatriate Christians working in the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, mostly Catholics from the Philippines, India, and Pakistan. As their numbers increased, the question of how—or whether—to allow them to openly practice their faith became a significant issue.

The Current Status of Arabian Christianity

In the West, the freedom to worship in any way one chooses has been a bedrock value at least since the late eighteenth century.

Lingering anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish restrictions in Europe or North America notwithstanding, the general trajectory has been one of growing tolerance for the modalities of faith. Perhaps the most notable example of this is also one of the earliest: the First Amendment to the U.S. constitution, which made illegal “prohibiting the free exercise” of any religion by the federal government.

Rev. Andrew Thompson ,the senior pastor of Abu Dhabi’s St. Andrew’s Church, astonishingly told a local newspaper that it is “easier being a Christian here [in Abu Dhabi] than it is back in the United Kingdom.”

Because of its deep-rooted nature within their societies, Westerners tend to frown on other societies that do not share the same ethic. Yet given the Middle East’s importance to their strategic and economic interests in the post-World War II era, Western chancelleries turned a blind eye to the glaring gap between believing in freedom of religion and interacting with those who flagrantly violated this principle. It was only after the 9/11 attacks and the attendant “war on terror” that Muslim intolerance of other faiths began to come under greater scrutiny.

Thus, an editorial in a British news-paper laments that Christians in the countries of the GCC are virtually “servants, abominably treated. Their religion must be practiced in secret, with converts threatened with death.”[1] Another writer went on to explain the emotional significance of this denial of a basic human right:

Most of the Christians who have come here have done so in order to find work in the Arab lands, and as a result, the majority live alone, having left their spouses and families back in their home country. As a result the parish, and also their Catholic faith, is like a piece of home for them.”[2]

The welfare of Christians in Saudi Arabia is particularly pressing because the government bans all non-Islamic religious practice alongside an aversion to non-Wahhabi Islamic creeds.

Yet the severity of the lack of Christians’ right to unencumbered religious freedom is all too often camouflaged by their own clerics who fear antagonizing the Gulf authorities. Rev. Andrew Thompson, the senior pastor of Abu Dhabi’s St. Andrew’s Church, astonishingly told a local newspaper that it is “easier being a Christian here [in Abu Dhabi] than it is back in the United Kingdom.”[3] According to Bill Schwartz, canon of the Anglican Church of the Epiphany in Doha: “In the Gulf, excluding Saudi Arabia, government attitudes are more [ones of] religious tolerance than religious freedom.”[4]

Spreading the Gospels through missionary activity is also severely curtailed among the member states of the GCC. Roy Verrips, the South African administrator of the Evangelical United Christian Church of Dubai, addressed this in diplomatic terms: “We respect and work within the boundaries they set for us” noting that his church had no issue with its members talking to others about Christianity in a private capacity.[5] In Bahrain, the authorities allow priests to spend time with Christian workers living on work sites and to join together in worship. However, “any form of mission among Muslims is forbidden everywhere [in the GCC states].”[6]

The first church in Kuwait was built in 1931, known as the “National Evangelical Church,” but there remains an acute lack of churches in the country. Every Friday in Kuwait City, 2,000 Christians cram into the 600-seat Holy Family church or listen outside to the mass, prompting the Catholic bishop to worry about a stampede.

The acute lack of churches to accommodate the spiritual needs of the numerous Christian denominations in the GCC states is another serious matter. While the church space problem is ubiquitous in the Gulf region, the following example indicates its magnitude. Every Friday in Kuwait City, 2,000 Christians cram into the 600-seat Holy Family church or listen outside to the mass relayed on loudspeakers, prompting their Catholic bishop, Camillo Ballin, to worry about a stampede: “If a panic happens, it will be a catastrophe … it is a miracle that nothing has happened.”[7]

Limits on the number of allowed churches and entry restrictions on Christian clerics hinder the ability of priests to serve their congregations adequately since each one of them

has to celebrate several masses at the weekend, and many parishes also have very distant outstations. The work of the priest is taken above all in this sacramental service, for in addition to the celebration of Mass, there are also baptisms, marriages, and funerals.[8]

Bishop Paul Hinder, who oversees Catholic churches in the GCC states and Yemen, noted the role of lay volunteers in keeping the church going: “It is a Church resting on the shoulders of the laity.”[9]

Islamic Notions of Religious Tolerance

What are then the underlying causes of this predicament?

For Muslims there is no deity but God. This is the lens through which they interpret all other religions, and this view explains why many Muslims do not understand Christianity. For them, the Qur’an is the final word of God. By and large, Muslims may tolerate some latitude in the ability of Christians to exercise their religious duties within the frame-work of the legally and institutionally inferior “protected communities” (or dhimmis), but the Christian faith must not be given the chance to flourish.

The Christianity of the Qur’an was embroiled in a debate about the nature of Christ, leaving the impression that its followers disagreed about what their faith actually consisted of. As a consequence, early Muslims considered Christianity a blasphemous interpretation of the nature of Jesus, who is presented in the Qur’an as a prophet but not the son of God. This perception persists and has lost none of its intensity.

Limited religious forbearance is the best that Christians can hope for in Gulf region countries.

Religious pluralism as understood in the West does not exist anywhere in the Gulf region, and limited forbearance is probably the best that Christians can hope for in these deeply conservative countries. However, on paper, the GCC states do practice religious tolerance. Thus, the sultanate of Oman has been seen as one of the most tolerant in the peninsula. Christian worship is protected through that country’s Basic Law, which prohibits discrimination based on religion and considers it a criminal offense to defame any faith. Similarly, the Kuwaiti constitution theoretically provides for religious freedom. But reality tells a different story. In 2014, according to the official figures, locals accounted for some 1.2 million of Kuwait’s 4-million-strong population while expatriate Muslims totaled another 1.8 million and expatriate Christians about 700,000 (the remaining residents belonged to polytheistic religions).[10] Yet the emirate has over 1,000 mosques and only seven churches; also, the government imposes quotas on the number of clerics and staff in legally authorized churches and pressures Kuwaitis to refrain from renting apartments or villas for use as unofficial churches.[11]

Likewise, Article 32 of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) constitution guarantees the “freedom to exercise religious worship … in accordance with established customs and provided it does not conflict with public policy or violate public morals.”[12] That final caveat—”provided it does not conflict with public policy or violate public morals”—is the crucial stipulation; however, it flips constitutional provisions on their heads. Even in states run by autocrats—or perhaps precisely because they are run by autocrats—public opinion in these matters counts for a great deal. In the UAE and other GCC states, government capacity to grant true religious freedom to Christians is highly restricted because their devout publics are still not at ease with such freedoms. Indeed, while Saudi Arabia stands out as the single GCC state that openly does not tolerate religious diversity, last year’s gesture of the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, the country’s effective ruler, to grant the land for a Hindu temple is a singular manifestation of pragmatism that does not necessarily demonstrate public approval.

Indigenous and Imported Christian Denominations

Another important factor explaining the GCC attitude toward religious pluralism in the peninsula is that until relatively recently, there were few non-Muslims for the inhabitants to encounter. Muslim tradition holds that, shortly before his death, the Prophet Muhammad expressed the view that in Arabia there should be only one religion, namely Islam. While a few pockets of non-Muslims held out for a period of time—the Jews of Khyber and the Christians of Najran, near Yemen[13]—shortly after Muhammad’s death one of his immediate successors, the caliph Umar, is said to have finished the job. Whether the eradication of non-Muslims from Arabia took place in precisely this fashion is less relevant than the reality, which is that there are few native Christians in the Persian Gulf states apart perhaps from several hundred in Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain.[14]

There are few native Christians in the Persian Gulf. The Protestant Church in Oman, above, is a branch of the Reformed Church of America, which began work in Oman in 1893. The church ministers to more than one thousand believers from sixty countries.

The modern history of Christianity in the Persian Gulf goes back to 1893 when a group of Christians arrived in Oman and bought a large building with a plot of land that they obtained as a gift from the sultan. This group, members of the Reformed Church of America, came for missionary purposes. A Catholic church, St. Peter and Paul, was founded there only in 1977, followed by an Orthodox, a Syriac Orthodox, and a Coptic church.

Bahrain claims to have the oldest church building in the Gulf region. Known as the National Evangelical Church, it was erected in 1906 by an American evangelical missionary of the Reformed Church in America.

In Kuwait, the establishment of the National Evangelical Church dates back to 1931. A Coptic church was built in 1958, later followed by an Armenian one. Even this limited Christian presence has for some years been the object of fierce political battles between the Kuwaiti emir and the Islamists. Wahhabi Salafism established itself in Kuwait following the Kuwait-Najd war of 1919-20; and while it is a minority movement, it wields enough influence to slow down the spread of religious tolerance in Kuwait.

At least two-thirds of the Christians in the GCC work in Saudi Arabia where they are completely cut off from contact with the church or clerical representatives. Unconfirmed reports claim that there are thousands of converts to Christianity in the desert kingdom who cannot profess their new faith because renouncing Islam is punishable by death.[15]

Effects on Foreign Communities

Although there is no clear-cut tie in the Gulf region between religious intolerance and the abuse of migrant workers, the fact that so many foreigners in the region are non-Muslims and from the lowest socioeconomic rungs likely plays a role in the attitude of the authorities toward notions of religious pluralism.[16] Abuse of non-citizen workers is wide-spread in the GCC states, as in many other countries around the world. In the Gulf states, abuse is not religion-specific even though it may overlap with religious intolerance at times.

Kenyan domestic workers in Saudi Arabia have reported mistreatment ranging from food and sleep deprivation to corporal abuse and molestation. In February 2015, family members of a Kenyan woman accused the woman’s Saudi employer of beating and torturing her to death. Above, family and friends carry her casket.

In truth, it is perhaps much easier to demand greater freedom of worship for Christians in the Gulf states than to curtail the abuse of foreign workers, irrespective of their faith, because such behavior is culturally embedded in the Arabian legacy of slavery. During its imperial moment in the Persian Gulf, the British government, torn between liberal politics and economic interests “generally tended to tolerate the institution of slavery in eastern Arabia.”[17] And while slavery was eventually abolished in most Gulf states, it persisted until 1964 in Saudi Arabia and 1970 in Oman, and the culture of slavery continues to pervade the region, especially in Saudi Arabia where it is “woven into the fabric of the psyche of the kingdom.”[18] In one of the countless episodes of abuse, Kenyan domestic workers in Saudi Arabia told disturbing stories of their abuse that ranged from food and sleep deprivation to corporal abuse and molestation.[19]

GCC officials persistently deny charges of abuse and dismiss them as cheap propaganda, but given the tight government censorship in the GCC states, which has long stymied local press outlets and journalists, there is little doubt that the full extent of abuse there is well under wraps.[20] That migrant workers continue to flood the labor market in the Gulf states helps defuse the pressure on the GCC states to deal with the issue.

Nevertheless, Gulf officials are keen on avoiding conflicts with the West over issues of abuse as well as religious freedom. Despite certain signs of displeasure among the locals, the Qatari leadership has tried over the last few years to promote the image of a modern state, building the Education City by Qatar (in 1997) and sponsoring major sport events in a drive for carving out a niche for itself on the world map. Thus, when Qatar opened the Church of Our Lady the Rosary in 2008, a government official expressed the hope that it would “send a positive message to the world.”[21] This, to be sure, does not prevent the emirate from closely monitoring the activities of Christian congregations, prohibiting them from advertising religious services but not banning them outright. In a similar step toward normalization and modernization, the UAE established diplomatic relations with the Holy See in 2007. According to Christian leaders, the Gulf governments struggle to strike a balance between the needs of their ever-growing foreign communities and the demands of their more conservative subjects.[22]

In 2012, the Saudi grand mufti called for the destructionof all churches inthe Arabian Peninsula.

A striking example of this struggle can be seen in a highly controversial fatwa issued in 2012 by the Saudi grand mufti, Sheikh Abdulaziz al-Sheikh, calling for the destruction of all churches in the Arabian Peninsula. Except for scant condemnation from Iraqi, Lebanese, and Egyptian Christians, Arab officials kept silent on such a serious issue. “How could the grand mufti issue a statement of such importance behind the back of his king?” was the naïve response by Christian bishops in Germany, Austria, and Russia.[23] The answer is that the Saudi royal family invariably appeases the country’s powerful religious establishment because Wahhabi clerics provide it with the religious legitimacy it needs to rule.

But opposition to building churches and Christian schools is also linked to conspiracy theories. Building churches in the name of freedom of worship is viewed with suspicion as it is frequently asserted that Westerners aspire to alienate Muslims from Islam by opening missionary schools in their countries. Opponents fear that church building will strengthen the hand of Christian missionaries and thereby prevent the spread of Islam among foreign workers while simultaneously sowing confusion and doubt in the minds of the Gulf population about Islamic norms and values.[24]

Conclusion

The GCC states go to great lengths to enhance their religiously-based popular culture and heritage as a means of asserting both sovereignty and political legitimacy. The UAE, for example, grounds its political authority in a deeply-rooted social contract that cements the ties between leaders and the citizenry with authentic traditions and norms.[25] These refer to the preservation of time-honored customs and values that are based on ethnic purity and religious uniformity. Saudi Arabia has taken this religious legitimization one step further by claiming a form of pan-Islamic leadership centered around its guardianship of Islam’s two holiest sites.[26]

The influx of foreign workers into the Gulf states—ranging between 50-90 percent of the total populations—poses a serious threat to the future of the indigenous social order by eroding the traditional values that provide the main pillar of regime legitimacy.[27] Riyadh claims foreign workers to be less than a third of the population; however, Saudi statistical yearbooks are misleading. The most recent population figure places the country’s total population at 30.8 million people, including 33 percent expatriate workers.[28] Saudi population estimates make no reference to the dependents of the expatriates or illegal workers. Saudi economic expansion relies “exclusively on the efforts of foreign workers, which official statistics tend to grossly underestimate.”[29] It is unlikely to have occurred to the GCC leaders that the foreign workforce would become a permanent feature, albeit at the bottom, of their demographic mosaic.[30]

The truth is that, notwithstanding the odd allusion to citizenship extension to expatriates, there is no intention whatsoever to integrate them, let alone any Christians into the fabric of GCC societies. Nor is there practically any chance that Saudi Arabia will allow the building of churches in the kingdom because it carries the risk of undermining the Saud dynasty’s traditional, religiously-grounded legitimacy, one that is already showing signs of erosion.[31]

Furthermore, as long as local Christian leadership maintains its timorous approach, lack of external pressure will just keep the status quo in place. This approach is best exemplified by Camillo Ballin’s response to a Kuwaiti parliamentarian’s call for the destruction of existing churches: “You have nothing to fear from us. We are partners in life. We respect your laws and your traditions.”[32] Elsewhere in the GCC states, the ruling elites will continue to extend calibrated gestures of goodwill to non-Muslims, yet it would be delusional to expect them to transcend their traditional perception of Christians as dhimmis and grant them unfettered freedom of religion, let alone fully fledged political rights and equality.[33]

**Hilal Khashan is a professor of political science at the American University of Beirut.

[1] The Guardian (London), Dec. 25, 2014. The GCC comprises the monarchies of Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

[2] Stefan Stein, “Christians in the Persian Gulf: ‘Our Faith is a piece of home,'” Aid to the Church in Need News (Aus.), Mar. 3, 2014.

[3] The Gulf News (Abu Dhabi), May 9, 2014.

[4] Reuters, Oct. 8, 2010.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Stein, “Christians in the Persian Gulf.”

[7] Reuters, Oct. 8, 2010.

[8] Stein, “Christians in the Persian Gulf.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Kuwait Demographics Profile 2014, IndexMundi, accessed May 4, 2016.

[11] Al-Rai (Kuwait), Oct. 17, 2015.

[12] Gulf News (Abu Dhabi), May 9, 2014.

[13] The survival of Jewish communities in Yemen and to a lesser extent Bahrain is largely attributable to the former’s rugged mountains and the latter’s insular island.

[14] Jean-Loup Samaan, “The Evolving Condition of Christians in the Gulf,” Italian Atlantic Committee, Rome, Jan. 13, 2014.

[15] The Voice of Martyrs (Streetsville, Ont.), accessed May 2, 2016.

[16] Western Christians in the Gulf states, who represent a mere fraction of Christian expatriates, are mostly highly paid professionals who are less affected by religious restrictions or abuse since they can congregate on private property.

[17] Matthew S. Hopper, “Slavery, Family Life, and the African Diaspora in the Arabian Gulf,” Itinerario, 3 (2006): 77.

[18] Graham Peebles, “Killed Beaten Raped: Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia,” Countercurrents.org, Kerala, India, Dec. 8, 2013.

[19] BBC News (London), Sept. 1, 2015; Daniel Pipes, “Saudis Import Slaves to America,” The New York Sun, June 16, 2005.

[20] Muftah (Doha), Feb. 5, 2015.

[21] Al-Jazeera TV (Doha), June 20, 2008.

[22] Reuters, Oct. 8, 2010

[23] Ibid., Mar. 23, 2012.

[24] Abdulaziz bin Ibrahim al-Askar, al-Tansir fi-l-Khalij al-Arabi (Riyadh: Dar al-Arabiya li-l-Mawsu’at, 2007), pp. 29, 102.

[25] Al-Ittihad (Abu Dhabi), Aug. 6, 2012.

[26] Al-Riyadh, Nov. 25, 2015.

[27] Ibid., Jan. 24, 2014.

[28] Arab News (Jeddah), Jan. 31, 2015.

[29] Hilal Khashan, Arabs at the Crossroads: Political Identity and Nationalism (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), p. 76.

[30] Al-Jazeera TV, Feb. 7, 2008.

[31] Daniel Pipes, “Churches in Saudi Arabia?” DanielPipes.org, updated Mar. 24, 2008.

[32] Al-Qabas (Kuwait City), Aug. 17, 2012.

[33] Daniel Pipes, “The Vatican Confronts Islam,” The Jerusalem Post, July 5, 2006.

Related Topics: Anti-Christianism, Kuwait, Persian Gulf & Yemen, Saudi Arabia | Hilal Khashan | Summer 2016 MEQ receive the latest by email: subscribe to the free mef mailing list This text may be reposted or forwarded so long as it is presented as an integral whole with complete and accurate information provided about its author, date, place of publication, and original URL.