Germany: Humor, Sultan Style

Stefan Frank/Gatestone Institute/April 19/16

Translation of the original text: Deutschland: Humor nach Art des Sultans

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has granted Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s demand for the criminal prosecution of comedian Jan Böhmermann, for a poem he wrote insulting Erdogan. Böhmermann is accused of violating a German law forbidding the “slander of institutions and officials of foreign states” — an offense carrying a penalty of up to five years in prison.

Erdogan once acquitted Sudanese President Omar al Bashir of genocide allegations: “Muslims cannot carry out genocide.” Erdogan was expressing an attitude widespread among German politicians and journalists: crimes are not crimes when Muslims commit them. Rarely is a Muslim despot or demagogue criticized in Germany; meanwhile no one has inhibitions about vilifying Christianity.

The signal that the German federal government has repeatedly sent to Turkey: We are totally dependent on and cannot live without Turkey. Is it really a surprise that Erdogan’s megalomania is increasing?

“The ‘cultural sensitivity’ practiced in liberal societies has nothing to do with sensitivity or thoughtfulness. It arises from the fear of violence.” — Henryk M. Broder, journalist and author.

Who would have thought that there is still a law in Germany that makes “lèse majesté” (offending the dignity of a monarch) a punishable crime? And that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is now benefiting from just that — and that it could plunge Germany into a (further) “national crisis.”

The terms “national crisis” and “governmental crisis” have been coming up again and again. In light of all the massive problems Germany has, this one is about a poem in which a cabaret performer and comedian, Jan Böhmermann, recently insulted the Turkish President. Erdogan has called for Böhmermann’s head and, as of last week, has Chancellor Merkel on his side.

The story began in March, when a German regional television station aired a music video during a satirical show, in which repression and human rights violations under Erdogan were pilloried in a humorous way. The Turkish government summoned the German ambassador and demanded that the video be removed from the internet and never be shown again. Germans thereby learned that the German ambassador is regularly summoned to Ankara — three times so far this year. According to reports, the Turkish government once complained about teaching material in Saxony’s schools that dealt with the Armenian genocide.

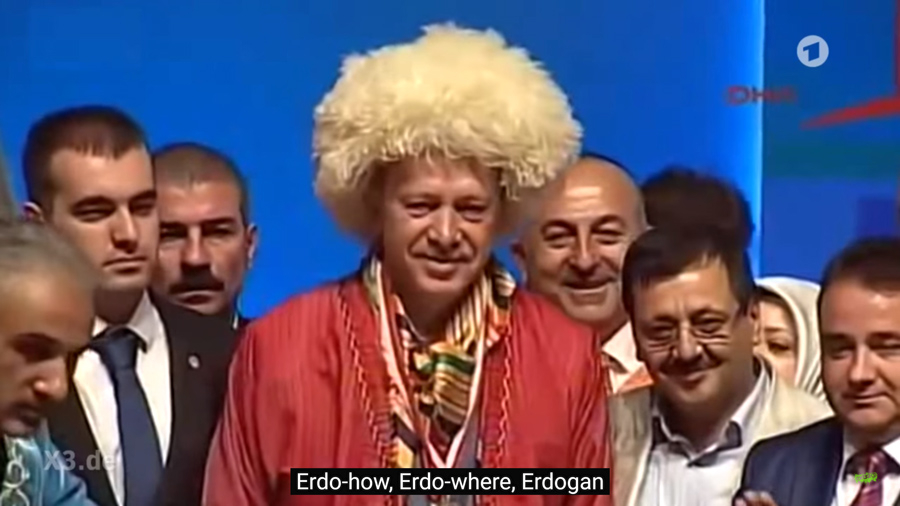

From the German satire video about Turkey’s President Erdogan.

The revelation that Erdogan is so easy to insult inspired some people to see if they could go the extra mile. Cabaret artist Jan Böhmermann published an “Offensive Poem” (its actual title) on ZDF Neo, a tiny state-run entertainment TV channel with a market share of 1%. It contained speculations about the Turkish president’s digestive and sexual preferences. AFP reports that, “In his ‘libelous poem’, which, as comedian Jan Böhmermann smilingly announced on television, openly exceeds the limits of free speech in Germany, Böhmermann accused Erdogan of having sex with goats and sheep, among other things.”

Böhmermann apparently mixed these unsubstantiated claims with (as an example) truthful statements on the oppression of minorities in Turkey (Erdogan wanted to “get Kurds, cut Christians,” he said).

Preemptive Surrender

In a preemptive surrender, which many Germans view as the real scandal, ZDF immediately deleted the broadcast from its Internet archives — before Erdogan could even complain. “The parody that satirically addresses the Turkish President does not meet the quality requirements the ZDF has in place for satire shows,” the station explained of this step. “For this reason, the passage was removed from the program.” This, as ZDF program director Norbert Himmler said, occurred “in consultation with Jan Böhmermann.” The limits of irony and satire were exceeded in this case

ZDF editors now criticize this course of action, and are asking for the piece to be accessible in the archives once again.

Chancellor Merkel — who is not otherwise known to react quickly to crises — tried to appease Erdogan shortly after the broadcast of the program. In a telephone conversation with Turkish Prime Minister Davutoglu, she called the poem “deliberately hurtful” and “unacceptable.” She probably hoped to settle things without having explicitly to apologize, which many Germans from across the political spectrum would resent. But Erdogan has no intention of settling down. He called for the criminal prosecution of Böhmermann. The public prosecutor’s office in Mainz is already investigating due to several complaints against Böhmermann and the managers of ZDF.

Laws from the German Empire

Laws, some of which date back to the German Empire, complicate the issue. Hardly any German has ever heard of them, but they have suddenly become relevant. In Germany, the term “abusive criticism” has primarily been familiar to lawyers; the fact that gross affronts are prohibited in Germany is probably obvious to many citizens. However, little known — and much less accepted — is a law from 1871, which makes the “slander of institutions and officials of foreign states” an offense carrying a penalty of up to five years in prison.

On April 14, Angela Merkel announced that she is granting the Turkish President’s demand for prosecution against Böhmermann — against the objections of her coalition partner, the Social Democratic Party (SPD).

In Germany, justice should decide such a case, not the government, says Merkel. But many commentators believe this justification to be hypocritical; after all, Erdogan supposedly already filed lawsuits as a private individual at the Court in Mainz. What Merkel will now enable is another court case for “lèse majesté.” The Berlin Tagesspiegel writes:

“The majority of Germans are against the fact that she [Merkel] is complying with Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s majesty demands in this way. ‘Majesty’ is, therefore, the appropriate term, because penal code section 103 from the year 1871 is for lèse majesté. So it comes from a time when we were still driving carriages and had an emperor. And the Turks had a sultan.”

Many also consider Merkel’s decision to be particularly absurd because on the same day, the Chancellor announced that she wants to abolish the law on lèse majesté “by 2018.”

Through her decision, Merkel signaled that the Turkish President’s “honor” is more important than that of normal German citizens, who can only take ordinary legal action when they are slandered, and who do not enjoy the privilege of an extended “protection of honor” for “princes.”

Erdogan has managed to extend what he already practices in Turkey to Germany. A few months ago, when nobody in Turkey had even heard of Jan Böhmermann, Die Welt reported:

“Paragraph 299 of the Turkish Penal Code, which provides for imprisonment of up to four years for insulting the head of state, has become the most common political offense. As a CHP party inquiry revealed, 98 people were arrested for this reason in the first ten months of last year. 66 were indicted, and 15 were kept in custody. The number of preliminary proceedings is unknown; human rights activists estimate several hundred. ‘With these reactions, Erdogan shows how justified this criticism is,’ said CHP human rights politician Sezgin Tanrikulu of Die Welt. ‘A regime that responds to all criticism with criminal proceedings is moving toward a dictatorship.'”

The Turkish penal code — now in Germany?

“Crimes Against Humanity”

The Turkish government called the slander of Erdogan a “serious crime against humanity.” The choice of words is reminiscent of how Erdogan once acquitted Sudanese President Omar al Bashir of genocide allegations in Darfur: “Muslims cannot carry out genocide.” Erdogan at the time was expressing an attitude often widespread in the West: crimes are not crimes when Muslims commit them. This also seems to be the view of many German politicians and journalists; rarely is a Muslim despot or demagogue criticized in Germany, while at the same time, no one in Germany has any inhibitions about vilifying Christianity or the Church.

It is this double standard, among other things, that Mathias Döpfner, CEO of the major German publishing house, Axel Springer, denounced in an open letter to Böhmermann, which was published in the daily newspaper Die Welt. In it, Döpfner calls for “solidarity with Jan Böhmermann.” He also writes:

“First, I want to say: I think your poem succeeded. I laughed out loud. So it’s important to me to say that, because in the past few days, there hasn’t been a single article about your text — whether accusatory or taking your side — that didn’t first (and at the same time captatio benevolentiae) emphasize how tasteless and primitive and insulting your satire about Erdogan was.”

According to Döpfner, it’s “as if you were to accuse a Formula 1 car manufacturer of having fast cars.” Being offensive is certainly the goal, and has a useful consequence: “It is very revealing what reactions your satire triggered. A focal point and a turning point.” Döpfner evokes various works by German artists, comedians, and cartoonists that are solely about mocking Christians and their faith. “When it comes to the provocation of religious or, more precisely, Christian feelings, anything goes in Germany,” says Döpfner. However, if someone offends Erdogan, that leads to “a kind of national crisis.”

Döpfner remembers how in Turkey, Erdogan proceeded against freedom of speech, minorities, and equality for women by force, and mentions the “excessive and reckless violence of the Turkish army” against the Kurds. Why, of all things, does insulting Erdogan cause such turbulence in Germany? Döpfner writes:

“For the small compensation of three billion euros, Erdogan regulates the streams of refugees so that conditions do not get out of control in Germany. You have to understand, Mr. Böhmermann, that the German government apologized to the Turkish government for your insensitive remarks. In the current situation, they are simply ‘not helpful’ — artistic freedom or not. You could easily call it kowtowing. Or as Michel Houellebecq phrased it in the title of his masterpiece on the self-abandonment of the democratic Western world: submission.”

Kowtowing to Turkey

Erdogan, who also campaigned in Germany during Turkish elections, appears to consider Germany an appendage of his Great Ottoman Empire. He calls out to Turks in Germany: “Assimilation is a crime against humanity.” He has great power in Germany. This is not only based on German organizations like the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB), which is controlled by the Turkish government, but above all on his ability to provoke upheaval in Germany if he wants. That Chancellor Merkel has delegated even more power to Erdogan in this situation, by imploring him to prevent hundreds of thousands of migrants in Turkey from heading for Europe, has made the situation even worse — particularly because she has explained over and over that this is the only solution to the migrant crisis.

Merkel considers it indecent when Europeans secure their own country’s borders based on current laws, but she gives Erdogan full reign to proceed with migrants at his discretion.

The signal that the German federal government has repeatedly sent to Turkey in the past is: We are totally dependent on and cannot live without Turkey. Is it really a surprise that Erdogan’s megalomania is increasing?

Someone needs to say: No, we do not need Turkey that badly. But regrettably, this response is not in sight. Instead, Germany and Europe will submit again to the sultan.

Böhmermann’s television appearances were canceled; he fears for his life and is under police protection.

The Fear in the West

The German journalist and writer Henryk M. Broder has long criticized the capitulation of the West in the face of dictators and Muslim rioters. In 2006, he published the book, Hurray, We Surrender! On the Desire to Buckle. Asked by Gatestone Institute for his thoughts on current events, Broder wrote:

“Appeasement is an English word, but part of German political culture. It is founded on the saying: the wise give in. Indeed, it is not the wise who give in, but the weak, who dispense their inferiority as wisdom. If the Pope is offended by tasteless caricatures, he writes a letter to the editor, or he says nothing. But he does not threaten violence; he certainly doesn’t have any suicide bombers he could send out.

“The ‘cultural sensitivity’ practiced in liberal societies has nothing to do with sensitivity or thoughtfulness. It arises from the fear of violence. The threat scenario built up over years is not without effect. No artist wants to live as Salman Rushdie does, under a fatwa, or to be made a prisoner in his own home, like Kurt Westergaard.

“What you classify as ‘tasteless’ is a matter of risk assessment. You can explain the current situation with an old Jewish joke: Two Jews are taken to a concentration camp. They see an SS man. ‘Moshe,’ says one of the Jews, ‘ask what they’re planning to do with us.’ ‘Don’t be stupid, Shlomo.’ answered the other. ‘We shouldn’t provoke them; the Germans might get angry.'”

***Stefan Frank, based in Germany, is an independent journalist and writer.

© 2016 Gatestone Institute. All rights reserved.