April 13, 1975: the day that destroyed peace in Lebanon

Hussein Dakroub| The Daily Star/Apr. 11, 2015

On Sunday, April 13, 1975, I went to work as usual to The Daily Star offices located near my house, some 300 meters from Riad al-Solh Square in Downtown Beirut. It was my sixth year at Lebanon’s only English-language newspaper, working as a sub-editor and translator after spending my first five years from 1969 to 1974 working as a proofreader. The city’s peace on that horrible day, which would later be the catalyst for a bloody and devastating civil war that would kill more than 150,000 people and leave the country’s infrastructure in tatters, was shattered by what some local media dubbed the “Ain al-Rummaneh massacre.”

Shortly after, news broke that Kataeb Party militiamen opened fire on a bus carrying Palestinians passing in the east Beirut suburb of Ain al-Rummaneh, killing over 20, tension ran high in both the Muslim and Christian areas of Beirut. The streets were left deserted as people rushed home to follow up on the fast-moving, dramatic developments that would change the normal and peaceful lives of Lebanese for the worse for the next 15 years. However, the two sides traded blame for who was responsible for the bloody incident on the bus, which was driving through Ain al-Rummaneh as it crossed Beirut from the Palestinian Tal al-Zaatar refugee camp in the northeast on its way to the Sabra and Shatila camps in the southwest. The Kataeb accused Palestinian gunmen in the bus of opening fire on the militia’s supporters, killing a bodyguard of the party’s then leader Pierre Gemayel and another man, while the Palestinians charged Kataeb militiamen with spraying the vehicle with gunfire leaving several people dead.

The tension was soon accompanied by the din of sporadic gunfire, mortar attacks and bombings that reverberated throughout Beirut, further adding to the jittery citizens’ fears. Filled with tension and worries about the country’s fate, I entered The Daily Star’s newsroom to see colleagues, editors, reporters and photographers busy trying to follow up on the grave repercussions of the Ain al-Rummaneh incident.

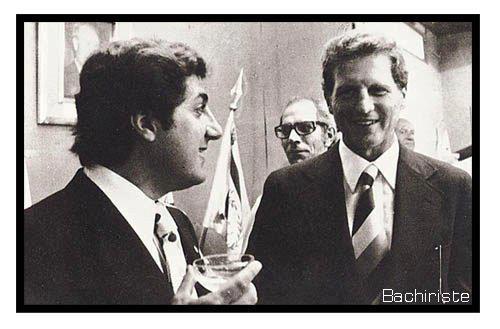

I remember hearing an American editor asking the then Editor-in-Chief Jihad Khazen: “What’s going to happen after the Ain al-Rummaneh incident?” to which Khazen replied: “I expect trouble.”

With no Internet or cell phones and not even a television set in the newsroom to follow up any breaking news, we relied, in addition to our reporters, on radio sets and Lebanese, Arab and foreign news agencies for urgent developments. We also relied on reporters from The Daily Star’s sister Arabic newspaper Al-Hayat, which had its offices in the same four-story building. Staying in the office until a late hour that day, some people would call the office to inform about explosions targeting shops owned by Christians on Hamra Street or the Kataeb headquarters in the Starco area.

I remember a Palestinian young man who used to deliver copies of the printed Palestinian news agency (named first as Kowat al-Assifa, Arabic for Storm Forces, and later as WAFA), brought the latest bulletin on that night carrying a strongly worded statement issued by Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat’s Fatah Movement. The statement accused what it called “Kataeb gangs” of committing a massacre against unarmed Palestinians.

In tandem with the fast-moving security developments, there was a flurry of activity by the country’s top political and religious leaders to try to prevent the situation from spinning out of control and descending into total chaos and sectarian warfare as many Lebanese feared. However, the most significant and alarming development came from an urgent meeting held by the so-called Nationalist Movement, a coalition of Syrian-backed leftist and Muslim parties, led by the influential Druze leader Kamal Jumblatt, which issued a statement late at night calling for the “isolation” of the Kataeb Party from the government in response to the Ain al-Rummaneh incident.

Many Lebanese Muslim leaders later acknowledged that the decision to isolate the Kataeb Party from the government was a big mistake because it deepened sectarian divisions at a time when the country’s Muslims and Christians were sharply split over the sensitive issue of the armed Palestinian presence in Lebanon. One of the editorials published by The Daily Star during the first few months of the war said that Lebanon gave the word “cease-fire” a bad name after hundreds of truce agreements were shattered hours after they were reached by the warring factions.

Soon after the war began The Daily Star, located on the confrontation lines between the rival militias, was forced by escalating fighting to close down in early 1976, I left Beirut with my family to south Lebanon where I stayed for several months until the capital was relatively safe to return. In the eyes of many Lebanese, particularly the leading Christian parties, the Palestinian military presence in Lebanon was the spark that triggered the 1975-90 Civil War.

A few years before the war broke out, pitting Muslim and leftist militiamen backed by Palestinian factions against Kataeb and other Christian fighters, tension was building up across Lebanon over the influx of arms and gunmen into the Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut and other areas, in defiance of Lebanese state authority and sovereignty. The late Pierre Gemayel, father of former President Amine Gemayel and slain President Elect Bashir Gemayel, would accuse Arafat’s PLO of running “a mini-state” within the Lebanese state.

The Kataeb Party and other Christian factions were the first to sound the alarm about the dire consequences of the proliferation of armed Palestinian presence in the country and called on the Lebanese Army to intervene to put an end to it. The repeated bloody clashes between the Lebanese Army and Palestinian guerrillas in south Lebanon and around camps in Beirut in the late 1960s and early 1970s provided the harbinger of what was in store for the multi-sect country.

In an attempt to prevent a renewal of fighting between the Army and PLO guerrillas, Lebanon was reportedly forced to sign the so-called Cairo Agreement with Arafat’s organization under the sponsorship of the late Egyptian President Gamal Abdel-Nasser in 1969. Although it had been approved by the Lebanese Parliament, the agreement, seen by many Lebanese leaders as an infringement on Lebanon’s sovereignty, gave Palestinian guerrillas the right to launch rocket attacks against Israel from certain bases in south Lebanon. However, Palestinian attacks on Israel invited retaliatory Israeli shelling and airstrikes against Lebanese towns and villages in the south.

As the Lebanese mark Monday the 40th anniversary of the Civil War, they wonder whether their bloody history will repeat itself, given the current political divisions and sectarian tensions fueled by the 4-year-old war in Syria. While the Lebanese were divided in the 1970s over the Palestinian military presence (with some Muslims supporting this presence and Christians opposing it), they are now sharply split over Hezbollah’s arsenal and its military intervention in Syria. Hopefully, having learned a tough lesson from the 1975 strife and seeing the daily bloodshed and sectarian fighting ravaging Syria and other Arab countries, the war-weary Lebanese will not indulge in a new bout of self-destruction.

“Civil war will never return to Lebanon because the Lebanese have been traumatized by its fire and they are not ready to slide again into a new cycle of self-killing,” Future Movement MP Mohammad Qabbani, a senior official of the Nationalist Movement in 1975, told The Daily Star Friday. “We must realize that our national unity is our guarantee and that no one can eliminate the other.”