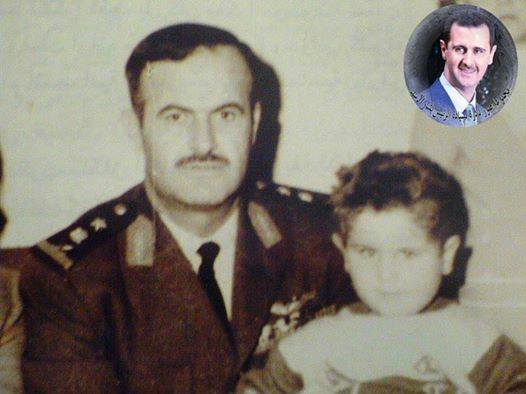

Like Father, Like Son

Amir Taheri/Asharq AlAwsat/Friday, 20 Feb, 2015

In the past few days I have been bombarded with messages drawing my attention to the emergence of a new chorus on Syria. The new song is sung by all sorts of people: British and American journalists, Israeli pundits and former officials, Russian and Iranian government mouthpieces, United Nations emissaries, and TV “experts” from east and west.

The new song is about Syria and it has this refrain: “Assad is part of the solution!” The narrative behind the new song is equally simple: the choice left in Syria is between bad (the Assad regime) and worse (the self-styled Caliph Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi).

One pro-Israel commentator asks: Why should we ditch the Assad family, who guaranteed the security of Israel’s borders for four decades, and risk having the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) massed close to Golan?

Assad is also cast as a lesser of the two evils when it comes to the future of Iraq. Since ISIS is seeking to dismember Iraq, wouldn’t it be wiser to help Assad, who would be happy to remain in his own neck of the woods even if that means massacring his own people? Even if Assad is succeeded by the Muslim Brotherhood and not ISIS, shouldn’t we be concerned about the threat that such a regime in Damascus might pose to others, notably Jordan and Egypt?

For his part Bashar Al-Assad, the man “re-elected” president of Syria with 99.9 percent of the vote in June last year, misses no opportunity to apply for his father’s old job as a pawn of big powers engaged in the deadly chess game that is the Middle East today. That was the tune that Hafez Al-Assad played when I first met him in 1973. At the time Tehran regarded him as an enemy. However, he used our interview to propose the idea of him switching sides and counter-balancing Iraq under Saddam Hussein, who was an enemy of Iran at the time. Once diplomatic channels moved into high gear, Assad succeeded in selling his new narrative to the Shah’s government.

A year after our interview I ran into Assad again during the Islamic Summit Conference in Lahore, Pakistan. Foreign Minister Abbas Ali Khalatbari—who headed the Iranian delegation—was reluctant to meet Assad, partly because he had no instructions on the subject from the Shah. The Pakistani hosts, however, were keen for Khalatbari to receive Assad. At the time, Pakistan was an ally of Iran and a member of the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) and its Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, whom I had known since 1971, believed that Assad could be “more useful inside the tent than outside.”

Bhutto was trying to prevent what he saw as a Soviet-India axis from dominating the region. In 1971, India backed by the USSR, had invaded and divided Pakistan into two halves, the eastern half becoming Bangladesh. In that context Bhutto had midwifed the US-China rapprochement and had also succeeded in wooing Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi away from the Soviets. So, it was no surprise that the Pakistani leader was keen to bring Hafez Al-Assad “on board.”

In the end, I believe the Pakistanis tried to force an “accidental” meeting between Khalatbari and Assad. This came one evening as Khalatbari was dining with four or five of us, when the Pakistanis suddenly informed him that Assad had left his villa and was heading for the villa reserved for the Iranian delegation. The dinner table was quickly cleared and the dessert postponed, and Assad arrived about 20 minutes later. During a meeting that lasted more than two hours, most of it devoted to mini-speeches by the Syrian despot, it became clear that Assad wanted to assure the Iranians on two points.

The first was that all his talk of socialism and Arab nationalism was nothing more than ideological pose. He was neither a pan-Arabist nor a leftist; he was Assadist.

The second point was that he was ready to work for anybody who paid. As a starter he was asking for an aid package of over 150 million US dollars, including cut-price oil and cash handouts. Having no instructions, all that Khalatbari could say was that he would report the request to the Shah. Later, the Shah approved Assad’s application, and the Ba’athist regime in Damascus was transferred from the list of enemies to that of “friends.”

A couple of days later, Bhutto, in a private conversation, asked me what I thought of his efforts “to bring Assad into the fold,” which meant weaning him away from the Soviets. Assad, of course, was embarking on his favorite sport of swimming with the tide. He had seen that Egypt’s Anwar Sadat had switched sides while Saddam Hussein in Iraq was deeply engaged in negotiations with Iran. The Chinese were also moving closer to the so-called Free World led by the US, strengthening a trend to isolate the USSR.

When I asked Bhutto what he thought of Assad, he described the Syrian leader as “The Levanter.” Knowing that, like himself, I was a keen reader of thrillers, the Pakistani Prime Minister knew that I would get the message. However, it was only months later when, having read Eric Ambler’s 1972 novel The Levanter that I understood Bhutto’s one-word pen portrayal of Hafez Al-Assad.

In The Levanter the hero, or anti-hero if you prefer, is a British businessman who, having lived in Syria for years, has almost “gone native” and become a man of uncertain identity. He is a bit of this and a bit of that, and a bit of everything else, in a region that is a mosaic of minorities. He doesn’t believe in anything and is loyal to no one. He could be your friend in the morning but betray you in the evening. He has only two goals in life: to survive and to make money.

President Bill Clinton described Hafez Al-Assad as “a man we could work with.” A few years ago, when he was rather chummy with the Assad clan, the then-Senator John Kerry believed that Bashar Al-Assad could be “useful like his father.” Former Israeli Foreign Minister Itamar Rabinovich echoed that sentiment.

Today, Bashar Al-Assad is playing the role of the son of the Levanter, offering his services to any would-be buyer through interviews with whoever passes through the corner of Damascus where he is hiding. At first glance, the Levanter may appear attractive to those engaged in sordid games. In the end, however, the Levanter must betray his existing paymaster in order to begin serving a new one. Four years ago, Bashar switched to the Tehran-Moscow axis and is now trying to switch back to the Tel-Aviv-Washington one that he and his father served for decades.

However, if the story has one lesson to teach, it is that the Levanter is always the source of the problem, rather than part of the solution. ISIS is there because almost half a century of repression by the Assads produced the conditions for its emergence. What is needed is a policy based on the truth of the situation in which both Assad and ISIS are parts of the same problem.