Originally published under the title, “Why the Hezbollah clash matters.”

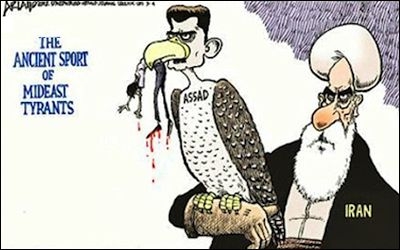

As the Assad regime is losing its grip over the country, Iran and its proxy, Hezbollah, both active defenders of the regime, are gaining greater freedom of action and trying to change the status quo along Israel’s northern border. Both are ideologically committed to the destruction of Israel and are trying to establish a new operations stage against Israel on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights — something that Assad has resisted for years.

Hezbollah seeks an additional arena from where it can harm Israel, as conducting operations against the Jewish state from Lebanon is problematic due to domestic political constraints (primarily fear of escalation and spillover effects on the Lebanese economy). Iran has a perennial interest in bleeding Israel. Creating a new threat from Syria serves this purpose. A new front in Syria will also to enhance its ability to deter an Israeli attack on its nuclear installations.

A new front in Syria will enhance Iran’s ability to deter an Israeli attack on its nuclear installations.

The helicopter attack in Syria on senior commanders of Hezbollah and Iran, just beyond the border with Israel, seems to signal that Jerusalem will not tolerate the opening of a new front. It is not clear that the Israeli-enunciated red line will be effective. Hezbollah’s response — attacking an Israeli military convoy in the border area between the Golan Heights and Lebanon — was measured, but indicated a tit for tat modus operandi.

Israel’s counter-response was also measured, showing that the government was reluctant to escalate intentionally and preferred to contain the violence. This is also what transpires from Israel’s behavior in its war against Hamas during the summer of 2014. While Israel’s cautious response is laudable in many respects, the limited Israeli military response to Hezbollah’s attack does not enhance deterrence.

Deterrence can be enhanced, however, if Israel makes preparations for a large-scale operation against Hezbollah. This means building the necessary ground forces and training for Lebanese scenarios. Such a build-up process is not clearly evident so far, and Hezbollah might deduce that its huge arsenal (over 100,000 missiles) creates an effective deterrent. As the number of attacks on Israel from southern Lebanon increased in recent months, the long period of quiet since 2006 seems more fragile. Perhaps Hezbollah is less afraid to hit Israeli targets. Deterrence against highly motivated rivals such as Hezbollah is always temporary and wears off with time. Israeli restraint is not conducive to restoration of deterrence. Therefore, the capability to destroy the Hezbollah missile threat is needed for deterring this radical organization, but also in case Israel finds it necessary to address such a threat before it attacks the Iranian nuclear infrastructure.

Deterrence against highly motivated rivals is always temporary, wearing off with time. Israeli restraint is not conducive its restoration.

The attempts to change the security equation in the north call for a reassessment of Israel’s policies toward Assad. If he is no longer able to resist the desire of Iran and Hezbollah to perpetrate terrorist acts against Israel from beyond the Golan Heights, his usefulness for Israel becomes limited. It is true that the civil war in Syria, where bad guys fight bad guys, is a convenient strategic development. Moreover, Israel (among other actors) has very limited influence on the outcome of the bloody struggle, but the survival of the Assad regime should no longer be a factor in Israel’s strategic calculations.

Actually, the fall of the Assad regime is nowadays an Israeli interest. The demise of this regime would be a terrible blow to its regional allies — Iran and Hezbollah. Damascus, an old ally of Tehran, is the linchpin of the Shiite crescent. And Iran is the most dangerous enemy of Israel and the main source for regional instability. The fall of Assad would also weaken Hezbollah considerably. It would reduce Hezbollah-Iranian influence in Lebanon and make the Hezbollah military build-up a more complicated enterprise. A Hezbollah without Iranian control of Damascus might spare Israel the need to intervene militarily in Lebanon in order to deal with the missile threat.

An Israeli predisposition to discard Assad is useful in Jerusalem’s relations with Saudi Arabia, which loathes the Syrian regime.

If Assad falls, it is not clear what will happen in Syria, but it is certain that Sunni radical groups will be more influential and the struggle over controlling parts of the country will continue. Yet, substate groups are generally less of a security threat than states. Assad-led Syria still has a chemical weapons arsenal and there are reports that it is trying to revive its nuclear weapon program.

An Israeli predisposition to discard Assad is also useful in Jerusalem’s relations with Saudi Arabia, which loathes the Assad regime and understands that its fall will curtail the growing Iranian influence in the Middle East. It is the Iranian threat that constitutes the strategic glue between the two states.

Of course, the Obama administration does not grasp the Iranian threat and continues its ill-advised attempts to reach an agreement with Iran, which allows Tehran to keep its option to build nuclear weapons. It tries to strengthen Shiite control of Baghdad, seems to cooperate with Assad against ISIS, which turned out to be a mere strategic distraction, and accepts the Shiite Houthis’ takeover of Yemen. Therefore, the Syrian-Lebanese nexus could become another issue of divergence between Jerusalem and Washington. Consequently, the paralysis of Barack Obama’s Middle East policy increasingly becomes an Israeli concern as well.

*Efraim Inbar is director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, a professor of political studies at Bar-Ilan University, and a Shillman/Ginsburg fellow at the Middle East Forum.