Charlie Hebdo, Syria’s war and jihadist exhibitionism

Monday, 26 January 2015

Dr. Halla Diyab/Al Arabiya

In the words of BBC thriller show, The Fall, DSI Stella Gibson (Gillian Anderson) said, after her privacy was violated by a serial killer: “Modern life is such an unholy mix of voyeurism and exhibitionism,” and “people perpetually broadcasting their internal and external selves.”

So much can reflect on how modern violence can pride itself on exhibiting its atrocities on both personal and public domains. Modern jihadist terrorism is not an exception. It has been subscribing to this exhibitionist and self-broadcasting culture.

Modern jihadist exhibitionism

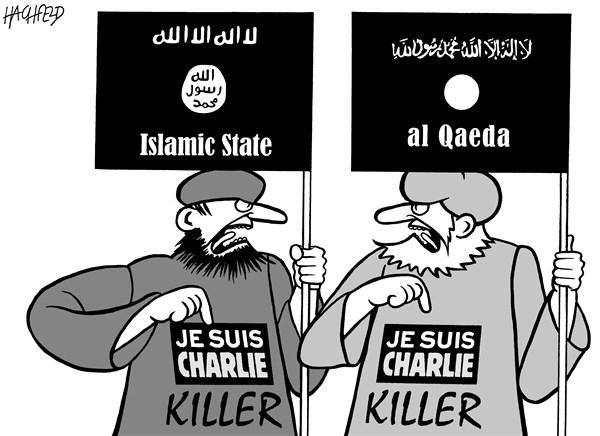

Although the Charlie Hebdo massacre carries the signature of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and despite the current hostility it has with ISIS, the massacre’s perpetrators internalize the rising face of modern jihadist exhibitionism which has defined ISIS’s “inward” strategy and its “importance of autonomy” culture.

With a bitter compulsion to seek public attention, one of the masked Kouachi’ brothers was described as proudly holding his index finger “skyward as he [reveled] in his crime before he [joined] his brother in a black getaway car” yelling and justifying his barbaric crime.

The scene of the cold-blooded murderer bragging in the middle of the street illustrates the psychology of the jihadists who derive their gratification from being observed by the very public they tend to terrorize. Exhibiting violence does not alienate nor marginalize the jihadist perpetrators; on the contrary, it pushes them to the center of the world’s attention which is what they yearn for. There are too many facets of how the modern jihadists desire to be seen and perceived publically. Hours after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, the Kouachi brothers were caught on CCTV with their masks off while robbing a petrol station at gunpoint in Villers-Cotterets.

“The current wars and so called “revolutions” in the Arab world inspire a deformed definition of freedom”With an impulsive compulsion to be publically identified, one of the Kouachis seemed comfortable walking around with his ammunition at the petrol station, filling a plastic bag with food, his face shamelessly visible. Although they do not view themselves as delinquents, the way homegrown jihadists introduce themselves to the public is shrouded with complex layers of customized façade.

They bounce on a dividing line between life and death, madness and reason, civilization and barbarism. On the other hand, fellow Paris attacker Amedy Coulibaly’s videos represent two facades of his identity. In the posts where he pledges allegiance to ISIS, he revived Osama Bin Laden’s videos appearing in a white gown [galabia], head wrapped, propping a gun laid on the wall to his right side and an ISIS flag on the wall above. Coulibaly addresses the world crossed legged on a modern wooden floor allegedly in a Parisian flat, conveying an implicit contradiction between the modernity suggested by the spatial surroundings, and the subconscious tendency of Coulibaly to adopt a traditional seated position normally seen in Jihadist videos. The scene portrays Coulibaly justifying a barbaric action within a civilized setting.

The post-Arab Spring era

The confusion in the modern Jihadist manifestations and the impact of the confused messages has been conveyed by the violence in the post-Arab Spring era and the Syrian war. The Arab Spring exposed the world to several scenes of extreme exhibitionist violence varying from witnessing the violent killing of Muammar Qaddafi to the obscene scenes of Syrian rebels allegedly eating the heart and liver of a Syrian soldier.

These acts of violence were filmed by their very perpetrators and shamelessly posted online to be watched, shared, and re-uploaded by millions. Both these acts were committed in the name of freedom and by those who advocate themselves as freedom fighters.

The kind of freedom these perpetrators promote is the senseless freedom of violence which they manufactured to legitimize their own inhumane acts. This brings into question what kind of freedom the Arab Spring and recent Middle East wars revive and inspire? Is freedom about the right to kill? Is freedom about the right to chop off heads? Is freedom about the right to eat and rip your opponent’s body apart?

The perpetrators shot to fame and were the center of global media attention. Exhibiting violence then became more volatile.

Alleged Syrian rebels claimed the beheading of a Christian man, 250 soldiers were publicly executed by ISIS in Iraq, a 17-year-old boy was crucified in Syria and Western journalists were beheaded on video.

There is no difference between the Paris attack as a cultural war against intellectual liberty and freedom of expression, and the killing of the Iraqi human rights lawyer; Salih al-Nuaimi who was seized and executed last September for criticizing ISIS on Facebook. These daily scenes of chopped heads and mutilated bodies are all justified, so the jihadists believe, on religious grounds, or for benevolent purposes; “to defend oppressed people.” By feeding this culture of violent exhibitionism, the current wars and so called “revolutions” in the Arab world inspire a deformed definition of freedom to young generations. Watching violence has gradually become an internet sensation, as despite people’s disgust and condemnations, they still watch those videos.