A Seismic Shift in Egyptian Public Opinion

Ali Ibrahim /Asharq Al Awsat

Wednesday, 14 Jan, 2015

Financial markets experts are well aware that psychological factors can sometimes play a marked role in the movements of the markets, whether positive or negative. Such factors are usually characterized by how much confidence there is among traders and fund managers with respect to a particular market. In the end, they are of course people like anyone else, subject to their whims and moods. When their mood is bullish and they feel confident about the market, they will begin to invest and pump money into the system. When their mood and confidence shift to the opposite end of the spectrum, however, they begin a process of frantic selling, bringing down the market with them.

This same is true of societies and political systems. If there is trust between each signatory to the social contract—the rulers and all their machinery of government, and the ruled with all their different societal groupings—then political disturbances become less frequent and government decisions meet with the approval of the populace, even when those decisions require great sacrifices.

In Egypt, indicators of public opinion suggest large chunks of the population came to view their rulers with suspicion over the last two decades. But it appears this has changed since the election of President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi last summer via a clear landslide and a massive tide of popularity firmly behind him.

This was made clear when Sisi decided to slash subsidies on fuel and food as part of necessary economic reforms. We could have seen a number of large protests and mass opposition to the decision, as happened during the eras of the last two presidents, Mohamed Mursi and Hosni Mubarak. However, this time there was a clear understanding among the public that this decision had to be made for the future good of the country, even if it was a bitter pill to swallow.

When the new administration took over the reins of power last year in what some are now calling “the Third Republic”—following the first inaugurated after the abdication of King Farouk in 1952 and the second after Egypt’s revolution in 2011—it was faced with a very heavy responsibility. The country’s economy was tanking after three years of instability adding to its already existing structural problems thanks to decades of mismanagement. On top of that, Egypt faced serious internal strife and dangers to its societal makeup and identity in those three years.

At the same time that many expected the new administration to fail in the face of these difficult challenges after its popularity in the street eventually waned, the street itself was keeping a close, somewhat tense, eye on how those in power would proceed. The previous choice of president, which came as a result of a moment of panic when Egyptians were forced to choose in a runoff between Mubarak’s former prime minister and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood—and which eventually saw the latter come to power—had been a catastrophic one, one that almost brought the country to the brink of a civil war. No one wants the new administration to fail as the previous one did, and no one has the luxury of “trying out” the new administration and seeing what it can do—as Egyptians were told to do when the Brotherhood came to power. Right now everyone, both inside and outside the country, is observing the situation closely, attempting to place their fingers firmly on the pulse of public opinion.

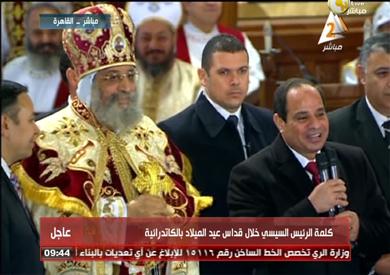

As far as this goes, there are currently some indicators which point unmistakably to public opinion being in support of the new administration. There are many who watched President Sisi’s warm reception at St. Mark’s Cathedral in Cairo when he went there to briefly attend Christmas Eve celebrations with some of the country’s Coptic Christian community. It was a different scene to those we have been used to seeing in Egypt during the period of Muslim Brotherhood rule, when suspicion was the more prevalent feeling the public had toward its rulers. There was a dangerous atmosphere in Egypt during that time, with extremists threatening to alter the country’s national identity. Another scene which indicates the new bond of trust between the public and the administration came during the sale of shares to the public to help finance the country’s new Suez Canal project. The public flocked in their thousands to banks and other public institutions both day and night in order to participate.

No one can say there has been a sudden or radical change in the daily lives of ordinary Egyptians. Many of the societal, political or economic problems that have accumulated in the country for decades still remain and no one expects them to be solved after a day, a year, or even many years to come.

What, then, has caused this shift in public opinion, and the trust and optimism Egyptians currently have toward the administration in power? The answer is simple: seriousness. Egyptians of different educational and social backgrounds all appreciate that no one can come along with a magic wand and solve all their problems at once. At the same time, however, problems, no matter how long they might take to solve, can be solved. This needs an administration that is serious about tackling these issues head-on. When people see their leaders are serious about solving problems they will follow in their footsteps and participate in the process. This is what has happened with the Sisi administration; this is how the president was able to win over public opinion.

The Reuters news agency published a report on Monday comparing the way Sisi has dealt with the bread subsidy problem to that of his predecessors Mursi and Mubarak. Both men failed to adequately solve the problem, but Sisi has succeeded in making the system more focused on those who need it by introducing a smart card system in several provinces across the country. This new system has been met with widespread public approval: lines are now shorter at state bakeries, everyone is able to get their share of bread, and consumption is down 30 percent due to a decrease in waste.

These success stories show what both Mursi and Mubarak failed to do. They also show that success is possible, that seriousness and a willingness to tackle problems head-on eventually yield fruit, no matter how difficult the problems