Iran: The Chained Volcano

Amir Taheri/Asharq Al-Awsat/September, 30/2022

إيران: البركان المقيد

أمير طاهري/الشرق الأوسط/الجمعة 30 أيلول 2022

«العملاق الأبيض المكبل بالسلاسل!»… هكذا يصف بهار، أحد أعظم شعراء إيران المعاصرين، جبل «دماوند»، البركان الشاهق الذي يَلوح في أفق منطقة طهران. في نهاية القصيدة، يناشد بهار البركان أن يضع حداً لصمته الدائم بانفجار مدوٍّ، مزلزل، قاذفاً بالنيران والحمم «لتطهير العالم من الطغيان والفساد».

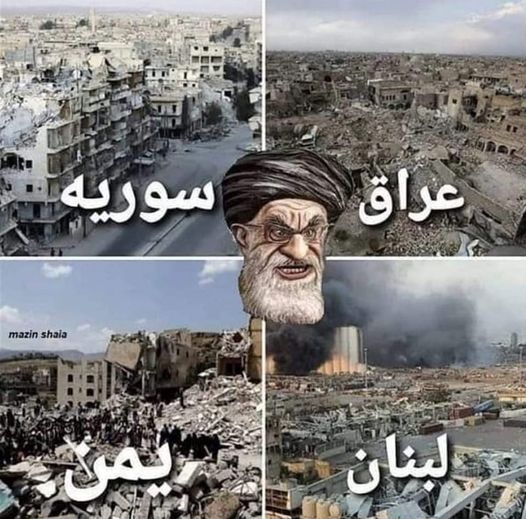

على مدى الأسبوعين الماضيين، ذكّرت الانتفاضة، التي عمّت أغلب أرجاء إيران، الكثير من الإيرانيين بقصيدة بهار، التي طرحت سؤالاً: هل بدأ البركان ثورانه الأخير؟ اليوم، جبل «دماوند» عبارة عن جيل جديد من الإيرانيين الذين لا يبالون البتة بخطاب الحكومة الإيرانية المبهم، ويفضلون الحياة في العالم الحديث بكل مناقبه ومثالبه، علاوة على نسخة المجتمع الكوري الشمالي الذي يحاول «المرشد الأعلى» علي خامنئي فرضها على إيران. اندلعت الانتفاضة بسبب موت مهسا أميني، صبية تبلغ من العمر 22 عاماً، في أثناء احتجازها لدى الشرطة بعدما كانت في زيارة عائلية في طهران. في غضون 24 ساعة من موتها، نتيجة لتعرضها للضرب على أيدي عملاء الأمن، كان اسم مهسا أميني معروفاً لدى جميع الإيرانيين تقريباً، وفي غضون يومين، صارت رمزاً لمقاومة الاستبداد في جميع أنحاء العالم. بسبب الرقابة والضغوط المفروضة على الصحافيين، بمن فيهم المراسلون الأجانب القلائل المتبقون، من الصعب في إيران قياس مدى ما يبدو أنه انتفاضة وطنية تحمل في جوهرها رسالة قوية: لا يمكننا التحمل أكثر من ذلك! وحتى وقت كتابة هذا المقال، تلقينا أسماء 84 شخصاً، من بينهم 9 نساء و6 أطفال، قُتلوا على يد جهاز الأمن الإسلامي، في حين تشير الأرقام شبه الرسمية إلى أن عدد الاعتقالات تجاوز 1800 مواطن.

وامتدت الانتفاضة إلى أكثر من 300 بلدة ومدينة، شهد بعضها احتجاجات للمرة الأولى في التاريخ الحديث.

لكن، هل هذا هو الانفجار العظيم الذي توسل به الشاعر بهار إلى جبل «دماوند»؟ على مدى الـ43 عاماً الماضية، أي منذ استولى الملالي على السلطة في طهران، كان البركان الإيراني يدفع بالكثير من الثورانات. في 8 مارس (آذار) 1979، أي بعد 25 يوماً من ظهور آية الله الخميني بوصفه الحاكم الجديد، احتشد أكثر من نصف مليون امرأة في طهران احتجاجاً على «الحجاب» المفروض عليهن، وغير ذلك من القيود التي أعلنها الملالي. ورغم القمع الوحشي والإعدامات الجماعية، شهدت إيران خلال الفترة من 1979 إلى 1988 ثورانات أخرى، حيث بدأت طبقات مختلفة من التحالف الذي تَشكّل في عهد الخميني تتلاشى. كما شهدت إيران في تلك السنوات مجازر ارتكبتها قوات النظام الجديد في عدة مناطق، لا سيما في خوزستان وكردستان وتركمان ساهرا. ومنذ ذلك الحين، شهد البركان الإيراني أكثر من 20 ثوراناً متوسطاً أو كبيراً، وقُمعت جميعها بوحشية.

في بداياته الأولى، وضع نظام الخميني الحفاظ على الذات كهدف أسمى له. وأطلق عليه الخميني اسم «أوجب الواجبات»، مؤكداً أنه لحماية النظام الحاكم يمكن تنحية الإسلام نفسه جانباً.

شرع الملالي في أمرين لحماية النظام:

أولاً، خصصوا جزءاً كبيراً من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي لقوات الأمن العسكرية. ويشير أفضل التقديرات إلى أن «حماية النظام» تستحوذ على 14 في المائة من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي، أي أكثر بأربعة أضعاف من مخصصات التعليم أو الصحة. ويبلغ عدد قوات حماية النظام، باستثناء الجيش الوطني، أكثر من 600 ألف جندي. وينتظم جهاز الأمن الإسلامي في 9 وحدات مختلفة، أربع منها على الأقل مُدربة ومُجهزة لقمع الاحتجاجات في الشوارع.

تستفيد جميع الوحدات الأمنية، بما فيها «الحرس الثوري»، من مزايا عدة، لا سيما الرواتب التي تزيد بنسبة 30 في المائة على الرواتب المماثلة في الجيش الوطني الإيراني.

كما أنها تملك أو تدير أكثر من 8000 شركة في ربوع البلاد، وتتحكم في 25 رصيفاً في 9 موانئ تستطيع من خلالها استيراد أو تصدير ما تشاء من دون القلق من اللوائح الجمركية. كما تسيطر قوات الأمن أيضاً على الكثير من الوظائف المهمة.

في الواقع، على مدى السنوات الخمس الماضية، وفيما يتعلق بشغل الوظائف الكبيرة، تقدموا كثيراً على الملالي. كما تُمنح لهم الأولوية في الوصول إلى الأماكن الجامعية، والسكن، والرعاية الصحية، والسلع الاستهلاكية، والسفر إلى الخارج، والمنح الدراسية لأبنائهم الذين يدرسون في أوروبا أو الولايات المتحدة.

كما أنشأ النظام سلسلة من الكيانات التي تعتمد على سخائه المطلق تحت أسماء مثل «عائلة الشهداء»، أو «المحرومين»، أو «أتباع سلالة الإمام»، أو «قراء النصوص المقدسة» (المداحون باللغة العربية)، أو «المتطوعين بالشهادة».

ينبغي أن يضاف لذلك شبكة من الملالي وطلاب الدين الذين يحصلون على رواتب و-أو «هبات» عرضية (تعرف باسم المظاريف الثقيلة) من «المرشد الأعلى».

وهناك دائرة أمنية أخرى تتكون من عشرات الآلاف من الإيرانيين المغتربين في أوروبا وأميركا الشمالية، والذين ينتقلون ذهاباً وإياباً، يمزجون العمل بالرفاهية، ويعملون كمدافعين عن النظام الإيراني في الخارج، ويُطلق عليهم اسم «المزدوجين» (ذوو الحياتين باللغة العربية).

مدى ضخامة القاعدة الموالية للنظام الحاكم في إيران لا تزال موضع نظر وتكهنات. في الانتخابات الرئاسية الأخيرة، فاز المرشح المفضل للنظام، آية الله الدكتور إبراهيم رئيسي، بربع أصوات الناخبين المؤهلين. وقدّر الرئيس السابق حسن روحاني أن نحو 30 في المائة من الإيرانيين كانوا سعداء بالنظام ووفّروا قاعدة الدعم الخاصة به. مهما كان حجم قاعدة دعم النظام، هناك أمر واحد مؤكد، وهو أنها تتقلص؛ إذ خلال الانتفاضة الحالية، وقف عدد غير متوقع من الشخصيات المرتبطة بالنظام والمستفيدة من مفاهيمه، بما في ذلك عدد مذهل من المشاهير والمسؤولين الإسلاميين السابقين، إلى جانب المتظاهرين علناً. فالشعراء الذين كتبوا عبارات الثناء على الخميني أو خامنئي، والروائيون الذين حاولوا تبرير كل خطأ وقع فيه الملالي، أعلنوا «توبتهم» على الملأ. تختلف الانتفاضة الأخيرة عن الانتفاضة السابقة في عدد من المناحي. إنها تجري على نطاق أوسع، وتجمع بين الناس من جميع مناحي الحياة. ولا يقتصر هذا النهج على المسائل المتعلقة بالشركات مثل تحسين الأجور وظروف العمل. كما أنها لا تركز على مظالم معينة مثل فقدان المدخرات، أو قمع الطوائف الدينية غير الإسلامية، أو القيود الثقافية. فهذه المرة، تتلخص الدعوة بشبه الإجماع تقريباً إلى تغيير النظام. لهذا السبب يبدو أن المؤسسة الحاكمة غير قادرة على اتخاذ قرار بشأن كيفية التعامل مع الانتفاضة. فقد دعا البعض داخل النظام إلى «القمع الوحشي»، في حين ينصح آخرون بالحوار وإصلاح بعض القوانين. حتى كتابة هذه السطور، التزم خامنئي -الذي ذرف الدموع على موت «جورج فلويد» في الولايات المتحدة- الصمت المطبق إزاء الثوران الذي هدد نظامه.

حتى إن لم يكن الثوران الأخير هو الثوران الكبير، هناك أمر واحد أكيد: أن بركان الغضب الإيراني لا يزال صاخباً ولا يمكن ترويضه بسهولة.

Iran: The Chained Volcano

Amir Taheri/Asharq Al-Awsat/September, 30/2022

“The white giant in chains!” This is how Bahar, one of Iran’s greatest contemporary poets, describes Mount Damvand, the towering volcano that looms over the horizon in the Tehran region.

At the end of his qasida (ode) Bahar pleads with the volcano to end its silence with an explosion of fire and lava to “cleanse the world of tyranny and corruption”.

For the past two weeks the nationwide uprising across Iran has reminded many Iranians of Bahar’s poem with the question: Has the volcano begun its final eruption?

Today’s Damavand is made of a new generation of Iranians who don’t give tuppence about the Islamic Republic’s arcane narrative, and prefer life in the modern world, warts and all, to the North Korean-style society that “Supreme Guide” Ali Khamenei is trying to impose on Iran. The uprising was triggered by the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year old woman on a family visit to Tehran.

Within 24 hours of her death, allegedly as a result of beatings by security agents, Mahsa Amini’s name was known to almost all Iranians and, within 48 hours, it had become a symbol of resistance to tyranny across the world.

Because of censorship and pressure exerted on journalists, including the few remaining foreign correspondents, in Iran it is hard to gauge the extent of what looks like a nationwide uprising whose core message is: We can’t take it anymore!

By the time of writing this column we had received the names of 84 people, including nine women and six children, killed by security while semi-official figures put the number of arrests at over 1800.

The uprising spread to over 300 towns and cities some of which witnessed protests for the first time in recent history.

But is this the big bang that Bahar begged Damvand to produce?

For the past 43 years, that is to say since mullahs seized power in Tehran, the Iranian volcano has produced numerous eruptions.

On March 8, 1979, that is to say 25 days after Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini emerged as the new ruler, over half a million women gathered in Tehran to protest against the imposed “hijab” and other restrictions announced by the mullahs.

Despite brutal repression and mass executions, throughout 1979 to 1988, Iran witnessed other eruptions as various layers of the coalition formed under Khomeini started to peel away. In those years Iran also witnessed massacres by the new regime’s forces in several regions, notably in Khuzestan, Kurdistan and Turkman Sahra.

Since then the Iranian volcano has witnessed over 20 medium or big eruptions, all of them brutally suppressed.

Early in its existence the Khomeinist regime established self-preservation as its highest goal. Khomeini called it “the obligation of obligations” (oujab al-wajebat in Arabic), asserting that to protect the regime even Islam could be set aside.

To protect the regime, the mullahs did two things.

First, they devoted a large chunk of the gross domestic product (gdp) to military-security forces. Best estimates indicate that “protecting the regime” claims 14 percent of the gdp, four times more than allocations for education or health. Regime protection forces, excluding the national army, number over 600,000 men. Islamic security is organized in nine different units, at least four of them trained and equipped for crushing street protests.

All security units, including Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC), benefit from numerous advantages notably salaries that are 30 percent higher than comparable ones in the national army.

They also own or manage over 8,000 businesses and control 25 quays in nine ports from which they can import or export whatever they like without facing customs regulations.

Security forces also get many of the plum jobs.

In fact, over the past five years, as far as filling big jobs is concerned, they have edged ahead of the mullahs. They are also given priority access to university places, housing, health care, consumer goods, foreign travel and scholarships for children studying in Europe or the United States.

Next, the regime created a series of groups dependent on its largesse under such names as “family of martyrs”, “the dispossessed”, “followers of the Imam’s line”, reciters of holy texts (maddahoun in Arabic), and “volunteers for martyrdom”.

To that must be added a network of mullahs and students of theology who receive stipends and/or occasional “gifts” (known as heavy envelopes) from the “Supreme Guide”.

Yet another security ring consists of tens of thousands of expatriate Iranians in Europe and North America who go back and forth, mixing business with pleasure while acting as the regime’s apologists abroad. They are called “double-lifers” (zu-hayatain in Arabic).

How large the regime’s base is remains a matter for speculation.

In the latest presidential election, the regime’s favorite candidate, Ayatollah Dr. Ibrahim Raisi won a quarter of the votes of eligible voters. Former President Hassan Rouhani, a mullah, estimated that around 30 percent of Iranians were happy with the regime and provided its support base.

Whatever the size of the regime’s support base, one thing is sure: it is shrinking. During the current uprising an unexpected number of figures associated with the regime and benefiting from its perks, including an amazing number of celebrities and former Islamist officials, have publicly sided with protesters. Poets who wrote odes in praise of Khomeini or Khamenei and novelists who tried to justify every misdeed of the mullahs have publicly “repented”.

The latest uprising is different from previous ones in a number of ways. It is taking place on a larger scale and bringing together people from all walks of life. It is not limited to corporatist issues such as better wages and working conditions. Nor is it focused on particular grievances such as loss of savings, oppression of non-Islamic religious communities or cultural restrictions. This time, the almost unanimous call is for regime change. This is why the ruling establishment seems to be unable to decide how to cope with the uprising. Some within the regime have called for “merciless repression” while others advise dialogue and reform of certain laws. Until this writing, Khamenei who shed tears for the death of George Floyd in the United States was silent on the eruption that threatened his regime. Even if the latest eruption isn’t the big bang, one thing is certain: The Damavand of Iranian anger is hissing and untamed.