Australian agencies must learn from their first major terrorist attack on home ground

DEBKAfile Special Report December 16, 2014

The 17-hour cycle of Australia’s first major Islamist terrorist experience at home, which began early Monday, Dec. 16, with a hostage siege at the Lindt chocolate café in Sydney’s bustling central business district, will have afforded its counter-terror services more operational lessons than any studies of past incidents or attacks in far-off places.

The 1996 Port Arthur massacre, in which Martin Bryant killed 35 people at the historic Port Arthur prison colony, was one of the deadliest shootings ever committed by a single person. Its outcome in another century was hardly relevant to this week’s hostage siege in Sydney, any more than the smaller incidents in the same city and Brisbane four months ago.

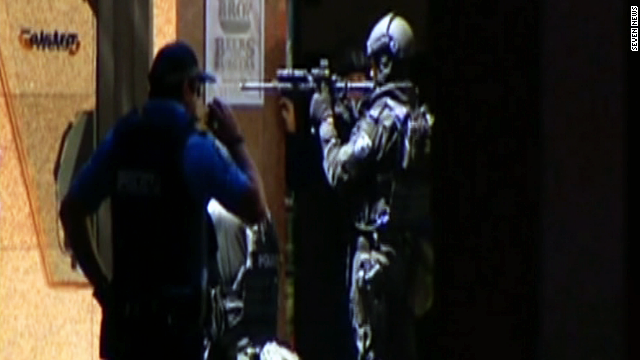

The Lindt affair was brought to an end by an armed commando raid on the darkened café to free the 15-30 hostages, two of whom were killed along with the lone hostage-taker, a dodgy self-styled sheikh who accumulated a long criminal record after reaching Australia as a refugee from Iran.

Compared with most counter-terror agencies in other parts of the world – especially at the hands of Islamist jihadis – the New South Wales police had some high-value advantages to work with: They were fed a steady stream of inside information through the hostages’ smart phones and social media; they were familiar with the scene in the besieged café from detailed descriptions by the five to ten hostages who managed to escape; they were supported by a disciplined, law-abiding public which respected police directives.

The hostage-taker, Man Haran Monis, who did not survive the commando raid, showed no sign of the bloodlust familiar from most radical Islamist outrages, although it is still not clear whether the two hostages who died in the last stage of the episode, the manager of the café, Tony Johnson, aged 34 and 38-year old barrister Katrina Dawson, were killed by Monis or by rescuers’ bullets.

Described by Prime Minister Tony Abbott as a “deeply disturbed individual”, he was not on any Australian terror watch list. But the national law enforcement agencies were all familiar with his criminal profile, could refer to clips depicting his public performances and were updated by the prisoners on how he was behaving and armed.

By dragging out the negotiations with pointless demands, the self-styled radical cleric treated religious fanatics of the world to a sustained dose of publicity as, hour by hour, TV screens flashed live broadcasts. A brief episode would have robbed the hostage-taker of this objective.

But it could have been shorter had trained army raiders split up into three groups at an earlier stage, stormed the café through two entrances and the glass frontage by clambering down from the roof by rope. Then, stun grenades and precise gunfire might have ended the episode sooner with fewer casualties.

However the interaction with the hostages, a critical increment for procuring advance intelligence on the availability of entrances and during the course of the operation, was not put to sufficient use for bringing it to a clean and speedy conclusion.

Our intelligence sources refer to the easily obtainable electronic-magnetic “dome,” which could have served to channel the cell phone communications from the hostages held in the Lindt café directly to the counter-terror service’s situation room. SMS messages, MMS images and video clips would have been beamed directly to the right address in an orderly fashion, instead of going round to the hostages’ relatives who had to be contacted by the police for this information.

The hostages could have been clued to use their video cameras to record images and conversations for live input on what was happening minute by minute in the siege café, and been warned to lie down and protect themselves, or escape, ahead of the commando assault.

Australia’s security services are no doubt making a close study of how the café siege unfolded and the improvements necessary for handling any potential terrorist attacks in the future.

Australia, which fights the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq as a member of the US-led coalition, is braced for a new phase of terrorism. Its security services are anxiously watching out for the possible return home of the estimated 70 Australians thought to be fighting with jihadis in the Middle East, or even for more lone wolf terror by individuals radicalized by jihadi ideology.