الجلسات العرفية المفروضة على الأقباط في مصر: المُروَّعُون (الضحايا) يُجبرون على الرضوخ لمشيئة المعتدين عليهم

ريموند إبراهيم/موقع التضامن القبطي/30 أكتوبر/2025

(ترجمة بحرية من الإنكليزية بواسطة الياس بجاني)

Egypt’s “Reconciliation Sessions”: The Terrorized Submit to the Terrorist

Coptic Solidarity/Raymond Ibrahim/October 30/2025

As first reported here, following Friday prayers on Oct. 24, 2025, a large Muslim mob rose against and “collectively punished” the Coptic Christians of the village of Nazlet Gelf in Minya, Egypt. This latest uprising was born of rumors that an 18-year-old Christian man and a Muslim girl were involved in a relationship. (On the logic that men are the natural leaders in relationships with women, sharia bans non-Muslim men from being involved with Muslim women, though Muslim men can be involved with non-Muslim women.)

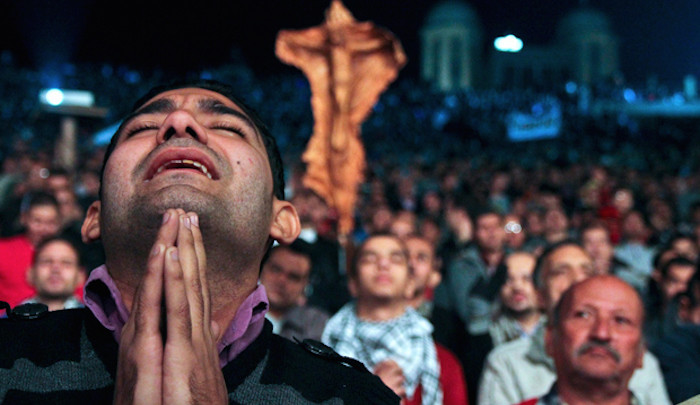

Due to this infraction, stones shattered windows, doors were battered, and Christian homes and properties were set ablaze by Muslims shouting threats and vowing to burn churches and expel all Christians. Viral footage captured the terror—including a frightened Coptic girl begging her mother for protection. As usual, security forces arrived and restored order only after the mob had sated its thirst for “vengeance.”

Then, instead of prosecuting the Muslim assailants—and as predicted—local authorities convened a so-called “reconciliation session” (جلسة عرفية) attended by village elders, officials, representatives of both families, and hundreds of villagers. The session’s decisions were, as expected, coercive, extralegal, and contrary to Egypt’s constitution. They included:

A fine of EGP 1 million on the young man’s grandfather, Napoleon.

A requirement for the young man’s father, Samih Ishaq, to sell his home and leave the village with his entire family.

Continued legal prosecution of the young man.

A ban on posting about the incident on social media.

A penalty clause of EGP 2 million if the agreement is violated.

Oversight of the agreement assigned to the village mayor.

The pronouncement—especially the expulsion of the Christian family—was greeted with triumphant applause, “Allahu Akbar” chants, and ululations from the Muslim majority. Coptic witnesses reported that the family accepted the terms only under extreme fear; their homes had already been attacked, and the extended family had fled to avoid casualties.

Meanwhile, the young man has been detained, pending further investigations by the public prosecutor on the “crime” he committed.

Quite telling in this “incident” is the deafening silence by Egypt’s political leaders, all the way to president El-Sisi regarding the imposed deportation of the Coptic families from the village, even though such an act is strictly prohibited by the Constitution, Art. 63, which states: “All forms of arbitrary forced displacement of citizens are forbidden. Violations of such are a crime without a statute of limitations.” Wouldn’t this explain that such assaults on the Copts are part of an institutionalized state policy?

Nazlet Gelf is far from an anomaly; this same exact pattern has played out repeatedly across Egypt. For example, in April of 2024, in al-Kom al-Ahmar, a Muslim mob attacked Christian homes after the minority received a permit to construct a church. Rather than pursue justice, authorities organized another of these closed-door “reconciliation sessions,” during which Christians were again pressured to forego charges in exchange for vague assurances that their church permit would remain intact (assurances that typically prove worthless).

Five years prior, on April 30, 2019, in the village of Nagib, reconciliation sessions similarly nullified protections under Egypt’s Church Construction Law, allowing attackers to escape accountability while Copts were forced to acquiesce to Muslim sensibilities.

The structure of these sessions follows a “good cop/bad cop” routine. Authorities, acting as the “good cops,” urge Christian leaders to accept further concessions to appease the rioting Muslims mob—the “bad cops”—lest things get even worse, with little that they, the authorities, can do about it. Christians are told to close churches temporarily, attend services in neighboring towns, and leave their homes and villages (as in the present case)—in short, comply with the mob’s arbitrary demands.

Copts are further “reminded” that any attempt to seek legal redress above and beyond the reconciliation session will only invite further retaliation. Christian youths who defend their homes or churches are often arrested, detained for hours or days, and threatened with charges—unless, of course, the Christian leaders agree to the humiliating terms of the sessions.

Reconciliation meetings thus institutionalize the punishment of victims and the impunity of perpetrators, under the guise of “reconciling” without getting the law involved.

Tellingly, the official response from Egypt’s Ministry of Interior only confirmed this pattern of denial and inversion. In its statement on the Nazlet Gelf attack, the Ministry rejected any religious motivation, describing the assault merely as “a dispute between two families… following a relationship between a young woman and a member of the other family,” while lamenting that “some parties attempted to give the incident a sectarian dimension.” It added that “the two families reconciled during a customary reconciliation session in accordance with the traditions and customs of the village,” adding that this “does not conflict with the legal measures taken.”

In other words, the government narrative erases the religious element entirely—reducing an organized Muslim mob’s attack on Christian homes to a “family dispute”—while glorifying the extralegal reconciliation session as a legitimate resolution. The Ministry’s warning against those who “exploit the incident to undermine the spirit of brotherhood and national unity” only reinforces the state’s priorities: suppress discussion, preserve appearances, and deny that Christians were targeted because of their faith.

The outcome in all such “state approved” sessions is predictable and consistent: the attackers emerge triumphant, emboldened to repeat their offenses, while the Christian victims pay the price with their freedoms, homes, property, and security. The system creates a veneer of legality and “harmony,” while in reality it enforces a hierarchy in which Copts occupy a highly precarious and subordinate position. The ostensible goal of social cohesion masks a deliberate subordination, turning every attack into an opportunity to reinforce minority vulnerability.

Bishop Makarious of Minya, commenting in 2024 on the persistent assaults against Christians, noted bluntly: “As long as the attackers are never punished, and the armed forces are portrayed as doing their duty, this will just encourage others to continue the attacks, since, even if they are arrested, they will be quickly released.”

Nazlet Gelf demonstrates that this pattern endures. Law, justice, and constitutional protections are consistently subordinated to social engineering designed to appease the Muslim majority at the expense of the Christian minority. Far from being isolated incidents, these events are part of a systematic approach in which Muslim attacks on Copts—often presented in Egyptian media as “sectarian violence”—are tolerated, perpetrators rewarded, and victims coerced into silence and displacement.

In short, reconciliation sessions are not conciliatory; they are instruments of state-sanctioned coercion. They convert acts of violence into a theatrical display of communal resolution while ensuring that the only beneficiaries are the aggressors. The victims—Christians who already navigate a web of legal obstacles to build churches or maintain property—are left to absorb the costs: financial, psychological, and physical. The state quietly approves, the law is bypassed, and the discrimination and violence continues with official acquiescence.

https://www.raymondibrahim.com/10/30/2025/articles-of-the-day

الجلسات العرفية المفروضة على الأقباط في مصر: المُروَّعُون (الضحايا) يُجبرون على الرضوخ لمشيئة المُعتدين عليهم

ريموند إبراهيم/موقع التضامن القبطي/30 أكتوبر/2025

(ترجمة بحرية من الإنكليزية بواسطة الياس بجاني)كما ورد أولاً هنا، فبعد صلاة الجمعة في 24 أكتوبر 2025، ثارت غوغاء مسلمة كبيرة ضد المسيحيين الأقباط في قرية نزلة جلف بالمنيا، مصر، و”عاقبتهم بشكل جماعي”. وُلد هذا التصعيد الأخير من شائعات تفيد بأن شابًا مسيحيًا يبلغ من العمر 18 عامًا وفتاة مسلمة كانا على علاقة. (استنادًا إلى المنطق الذي يرى الرجال قادة طبيعيين في العلاقات مع النساء، تحظر الشريعة على الرجال غير المسلمين الارتباط بالنساء المسلمات، على الرغم من أنه يمكن للرجال المسلمين الارتباط بنساء غير مسلمات).

بسبب هذه المخالفة، تحطمت النوافذ بالحجارة، واعتُدي على الأبواب، وأُشعلت النيران في منازل وممتلكات المسيحيين من قبل مسلمين كانوا يصرخون بالتهديدات ويتوعدون بحرق الكنائس وطرد جميع المسيحيين. وقد التقطت لقطات انتشرت بشكل واسع على الإنترنت حجم الرعب—بما في ذلك فتاة قبطية مذعورة تتوسل لأمها الحماية. وكالعادة، وصلت قوات الأمن وأعادت النظام فقط بعد أن روى الغوغاء عطشهم للانتقام.

الإكراه باسم “المصالحة”

بعد ذلك، وبدلاً من محاكمة المعتدين المسلمين—وكما كان متوقعًا—عقدت السلطات المحلية ما يسمى بـ “جلسة عرفية” حضرها شيوخ القرية، والمسؤولون، وممثلون عن كلتا العائلتين، ومئات من القرويين. كانت قرارات الجلسة، كما هو متوقع، قسرية وخارجة عن القانون وتتعارض مع الدستور المصري. وقد شملت:

غرامة قدرها مليون جنيه مصري على جد الشاب، نابليون.

إلزام والد الشاب، سميح إسحاق، ببيع منزله ومغادرة القرية مع عائلته بأكملها.

استمرار الملاحقة القانونية للشاب.

حظر النشر حول الحادث على وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي.

شرط جزائي قدره 2 مليون جنيه مصري في حال انتهاك الاتفاق.

إسناد الإشراف على الاتفاق إلى عمدة القرية.

استُقبِل النطق بالحكم—وخاصة طرد العائلة المسيحية—بتصفيق ظافر، وهتافات “الله أكبر”، وزغاريد من الأغلبية المسلمة. وأفاد شهود عيان أقباط أن العائلة قبلت الشروط تحت وطأة الخوف الشديد فقط؛ فقد تعرضت منازلهم بالفعل للهجوم، وفرت العائلة الممتدة لتجنب وقوع إصابات.

وفي الوقت نفسه، اُحتجز الشاب، بانتظار مزيد من التحقيقات من النيابة العامة بشأن “الجريمة” التي ارتكبها.

الصمت الرسمي والمخالفة الدستورية

الأمر البالغ الدلالة في هذا “الحادث” هو الصمت المطبق من قبل القادة السياسيين في مصر، وصولاً إلى الرئيس السيسي، بشأن الترحيل القسري المفروض للعائلات القبطية من القرية، على الرغم من أن مثل هذا الفعل محظور قطعًا بموجب المادة 63 من الدستور، والتي تنص على: “يحظر كل صور التهجير القسري التعسفي للمواطنين. ومخالفة ذلك جريمة لا تسقط بالتقادم.” ألا يوضح هذا أن مثل هذه الاعتداءات على الأقباط هي جزء من سياسة دولة مؤسسية؟

نمط متكرر

إن نزلة جلف أبعد ما تكون عن كونها حالة شاذة؛ فقد تكرر نفس هذا النمط تمامًا مرارًا وتكرارًا في جميع أنحاء مصر. ففي أبريل 2024، على سبيل المثال، في الكوم الأحمر، هاجم غوغاء مسلمون منازل مسيحية بعد أن حصلت الأقلية على تصريح لبناء كنيسة. وبدلاً من السعي لتحقيق العدالة، نظمت السلطات جلسة أخرى من هذه “الجلسات العرفية” المغلقة، حيث ضُغط على المسيحيين مرة أخرى للتنازل عن التهم مقابل تأكيدات غامضة بأن تصريح كنيستهم سيظل ساريًا (تأكيدات غالبًا ما تثبت أنها لا قيمة لها).

قبل خمس سنوات، في 30 أبريل 2019، في قرية نجيب، ألغت جلسات المصالحة بشكل مماثل الحماية بموجب قانون بناء الكنائس في مصر، مما سمح للمعتدين بالإفلات من العقاب بينما أُرغم الأقباط على الإذعان لمشاعر المسلمين.

يتبع هيكل هذه الجلسات روتين “الشرطي الجيد/الشرطي السيئ”. السلطات، التي تعمل كـ “الشرطي الجيد”، تحث القادة المسيحيين على قبول مزيد من التنازلات لاسترضاء الغوغاء المسلمة الهائجة—”الشرطي السيئ”—كي لا تزداد الأمور سوءًا، مع قليل مما يمكنهم، أي السلطات، فعله حيال ذلك. يُطلب من الأقباط إغلاق الكنائس مؤقتًا، أو حضور الصلوات في البلدات المجاورة، أو مغادرة منازلهم وقراهم (كما في الحالة الحالية)—باختصار، الامتثال للمطالب التعسفية للغوغاء.

يتم “تذكير” الأقباط أيضًا بأن أي محاولة لطلب تعويض قانوني يتجاوز الجلسة العرفية لن يؤدي إلا إلى مزيد من الانتقام. غالبًا ما يُقبض على الشباب المسيحيين الذين يدافعون عن منازلهم أو كنائسهم، ويُحتجزون لساعات أو أيام، ويُهددون بتوجيه تهم إليهم—إلا إذا وافق القادة المسيحيون، بالطبع، على الشروط المُهينة للجلسات.

مؤسسة لعقاب الضحية

وبالتالي، فإن اجتماعات المصالحة تؤسس لعقاب الضحايا وإفلات الجناة من العقاب، تحت ستار “المصالحة” دون تدخل القانون.

ومن اللافت للنظر أن الرد الرسمي من وزارة الداخلية المصرية أكد هذا النمط من الإنكار والقلب. ففي بيانها حول هجوم نزلة جلف، رفضت الوزارة أي دافع ديني، واصفة الاعتداء بأنه مجرد “نزاع بين عائلتين… على خلفية علاقة بين شابة وفرد من العائلة الأخرى،” بينما أعربت عن أسفها لمحاولة “بعض الأطراف إعطاء الحادث بُعدًا طائفيًا.” وأضافت أن “العائلتين تصالحتا خلال جلسة صلح عرفية وفقًا لتقاليد وعادات القرية،” مضيفة أن هذا “لا يتعارض مع الإجراءات القانونية المتخذة.”

وبعبارة أخرى، تعمل الرواية الحكومية على محو العنصر الديني بالكامل—مختزلة هجوم غوغاء مسلمة منظمة على منازل مسيحية إلى “نزاع عائلي”—بينما تمجِّد جلسة المصالحة الخارجة عن القانون بوصفها حلاً شرعيًا. إن تحذير الوزارة ضد أولئك الذين “يستغلون الحادث لتقويض روح الأخوة والوحدة الوطنية” يعزز أولويات الدولة: قمع النقاش، والحفاظ على المظاهر، وإنكار أن المسيحيين كانوا مستهدفين بسبب إيمانهم.

عواقب نظامية

إن النتيجة في جميع هذه الجلسات “المُجازة من الدولة” يمكن التنبؤ بها ومتسقة: يخرج المهاجمون منتصرين، وأكثر جرأة على تكرار جرائمهم، بينما يدفع الضحايا المسيحيون الثمن بحرياتهم ومنازلهم وممتلكاتهم وأمنهم. يخلق النظام قشرة من الشرعية و “الوئام”، بينما يفرض في الواقع تسلسلاً هرميًا يشغل فيه الأقباط موقفًا بالغ الخطورة وتابعًا. فالهدف الظاهري المتمثل في التماسك الاجتماعي يخفي إخضاعًا متعمدًا، يحوّل كل اعتداء إلى فرصة لتعزيز ضعف الأقلية.

وعلق الأسقف مكاريوس، أسقف المنيا، في عام 2024 على الاعتداءات المستمرة ضد المسيحيين بصراحة: “ما دامت المعتدون لا يُعاقبون أبدًا، وتُصوَّر القوات المسلحة على أنها تقوم بواجبها، فإن هذا سيشجع الآخرين على مواصلة الهجمات، إذ إنهم، حتى لو قُبض عليهم، سيُطلق سراحهم بسرعة.”

تُظهر نزلة جلف أن هذا النمط صامد. فالقانون والعدالة والحماية الدستورية تخضع باستمرار لـ “هندسة اجتماعية” مصممة لاسترضاء الأغلبية المسلمة على حساب الأقلية المسيحية. إن هذه الأحداث، بدلاً من كونها حوادث معزولة، هي جزء من نهج منهجي يتم فيه التسامح مع الهجمات المسلمة على الأقباط—التي غالبًا ما تُقدَّم في وسائل الإعلام المصرية على أنها “عنف طائفي”—ويُكافأ الجناة، ويُكره الضحايا على الصمت والتهجير.

باختصار، جلسات المصالحة ليست تصالحية؛ بل هي أدوات للإكراه الموافق عليه من الدولة. إنها تحوّل أعمال العنف إلى عرض مسرحي للحل المجتمعي بينما تضمن أن المستفيدين الوحيدين هم المعتدون. أما الضحايا—المسيحيون الذين يتنقلون بالفعل عبر شبكة من العوائق القانونية لبناء الكنائس أو الحفاظ على الممتلكات—فيُتركون لامتصاص التكاليف: المالية والنفسية والجسدية. توافق الدولة بهدوء، ويتم تجاوز القانون، ويستمر التمييز والعنف بموافقة رسمية.