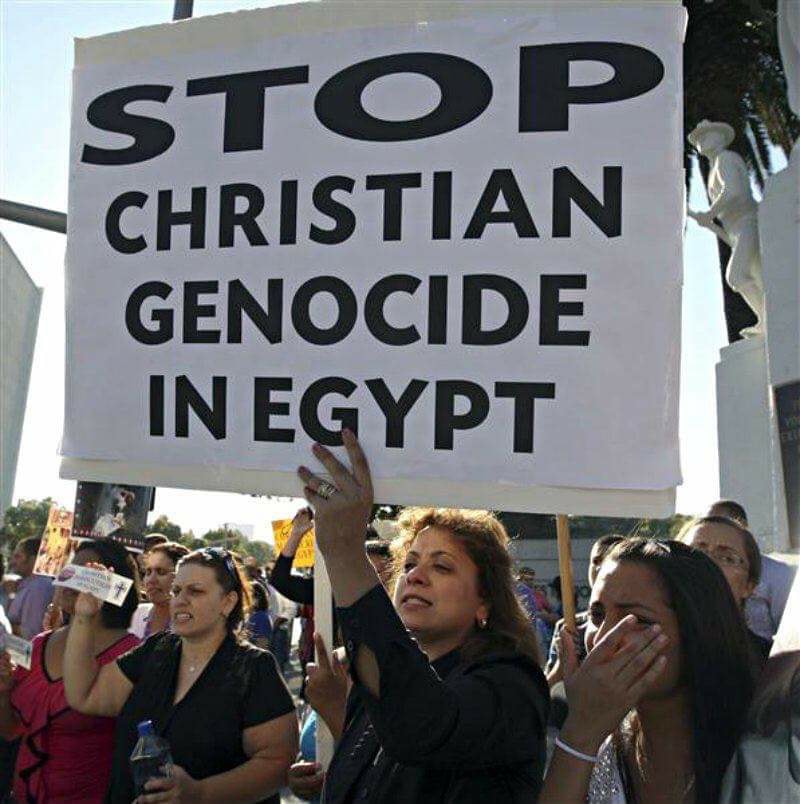

في اطار مسلسل اَضطهاد المسيحيين الأقباط في مصر/من إشاعة إلى اعتداء شامل…العقاب الجماعي لأقباط مصر

بقلم: ريموند إبراهيم/نقلاً عن موقع التضامن القبطي/ 23 تشرين الأول/2025

(ترجمة من الإنكليزية بحرية بواسطة الياس بجاني بالإتسعانة بمواقع ترجمة الكترونية)

In the context of the series of persecution of Coptic Christians in Egypt/

From Rumor to Rampage: The Collective Punishment of Egypt’s Coptic Christians

Raymond Ibrahim/Coptic Solidarity/October 23, 2025

On October 23, 2025, the village of Nazlet Jelf in Egypt’s Minya province became the latest site of anti-Christian violence. The trigger was familiar: rumors alleging a romantic liaison between a young Coptic man and a Muslim woman. As has so often been the case across Upper Egypt for centuries, the accusation alone sufficed to mobilize a mad Muslim mob.

Eyewitnesses reported scenes of chaos: “A large number of villagers surrounded the Copts’ homes,” one resident said. “They threw stones at the houses, breaking doors and windows. Fires were set in some of the farmland owned by the Copts. Women screamed repeatedly; children cried in terror. Even those with no connection to the alleged affair were attacked.”

The mob’s fury was indiscriminate, a collective punishment inflicted for violating Islamic sensibilities. According to one report, the attacks transformed a community once accustomed to a reasonable degree of coexistence into one gripped with fear. Residents described how moments of shared daily life—children playing together, neighbors visiting—turned, like the flip of a switch, into hatred, aggression, and terror.

Police eventually restored order (once the mob was sated) but the damage—physical and metaphysical—was extensive. Christian households kept their children home from school, afraid they would get attacked again. Many are looking into relocating.

Local officials offered the usual lip service: “Law must be applied to everyone,” they declared. Yet those familiar with Minya know that similar pronouncements have followed almost every comparable incident, rarely leading to any accountability.

Nazlet Jelf’s violent outburst is not an anomaly; it is the latest chapter in a centuries-long pattern of anti-Christian violence in Egypt. The mere accusation of transgressing sharia—which bans relations between Christian men and Muslim women—has been enough to mobilize Muslim mobs to collectively punish the Copts for nearly fourteen centuries.

Minya itself has a long record of such incidents. In past decades, militant Muslim groups like al-Gamaʿa al-Islamiya targeted Copts. Today, even without organized militancy, the logic of collective guilt persists: a rumor about a Christian man becomes a justification to terrorize his entire family and, by extension, his community.

Indeed, this most recent violence mirrors other egregious cases in Minya. In 2016, an elderly Christian woman, Soad Thabet, was publicly stripped naked, beaten, spat upon, and paraded through the streets of al-Karm village by hundreds of Muslim men—her only “crime” being that her son was accused of associating with a Muslim woman. Even as video evidence and eyewitness testimony clearly identified the attackers, they were acquitted.

“Though I am strong,” she later reflected, “it is sometimes hard for me to speak; I’m always fighting back tears and sometimes break down.”

As yet another example, in January 2012, a mob of over three-thousand Muslims attacked Christians in an Alexandrian village because a Muslim accused a Christian of having “intimate photos” of a Muslim woman on his phone.

Some months later, the village of Dahshur witnessed another large-scale attack on Copts after a Christian launderer accidentally burned a Muslim’s shirt. A brawl ensued, and in retaliation, some two-thousand Muslims attacked multiple Christian homes and businesses, causing widespread property damage and forcing dozens of families to flee.

All of these incidents demonstrate the enduring logic, first laid out in The Conditions of Omar, a key juridical text outlining Muslim and Christian relations: the offense of a single “dhimmi” justifies the collective punishment of an entire Christian community—a pattern repeated across centuries.

To the Muslim mob, the alleged “infraction” is not a private matter but a violation of divine and social order. Eyewitnesses in this latest uprising in Nazlet Jelf made this clear: “Even people with no relation to the accused were assaulted. The violence was indiscriminate. Fires were set. Houses were destroyed. Women and children were screaming for help.”

It is worth noting that many of these attacks occur on Fridays—the one day of communal Muslim prayer—when sermons and mosque gatherings often stir congregants to outrage over perceived offenses by non-Muslims. Ideological reinforcement, combined with long-standing social norms, ensures that collective punishment is not only tolerated but expected.

The rumors of a Christian man courting a Muslim woman, or minor disputes, thus become sufficient to mobilize a mob that perceives itself as enacting divine justice—as when thousands of Muslims attacked and burned Christian properties in another Minya province village on learning that a Christian household was about to have a mobile network booster installed on their roof..

In short, the most recent outburst in Nazlet Jelf follows a well-known script:

1. A rumor or accusation arises, often of a Christian “overstepping” his or her bounds and wounding Muslim sensibilities (by, for instance, dating a Muslim woman, trying to build or repair a church, etc.).

2. A Muslim mob gathers, compelled by collective notions of honor and religious obligation.

3. Coptic homes and property are attacked; women and children are terrorized.

4. Authorities intervene belatedly, restoring superficial order but rarely punishing the perpetrators.

5. Christians are compelled to “reconcile” with their attackers, without seeing any justice done, and brace themselves for the next time the pattern repeats.

The failure to punish offenders leads to the perception that such acts are acceptable. Impunity, reinforced over generations, normalizes collective punishment. In every case of the collective punishment of Copts, the same logic applies—and has for centuries: rumor + Islamic law + lenient enforcement = unchecked violence.

The script is old, familiar, and unbroken—and history will repeat itself so long as the conditions remain the same.

https://www.copticsolidarity.org/2025/10/26/from-rumor-to-rampage-the-collective-punishment-of-egypts-coptic-christians/

في اطار مسلسل اَضطهاد المسيحيين الأقباط في مصر/من إشاعة إلى اعتداء شامل: العقاب الجماعي لأقباط مصر

بقلم: ريموند إبراهيم/نقلاً عن موقع التضامن القبطي/ 23 تشرين الأول/2025

(ترجمة من الإنكليزية بحرية بواسطة الياس بجاني بالإتسعانة بمواقع ترجمة الكترونية)

في 23 أكتوبر 2025، أصبحت قرية نزلة جلف بمحافظة المنيا المصرية أحدث موقع للعنف ضد المسيحيين. كان المُحرِّض مألوفًا: إشاعات تزعم وجود علاقة غرامية بين شاب قبطي وامرأة مسلمة. وكما حدث مرارًا في صعيد مصر على مر القرون، كانت مجرد التهمة كافية لتحريك حشد مسلم غاضب ومُهيَّج.

أفاد شهود عيان بمشاهد من الفوضى: قال أحد السكان: “حاصرت أعداد غفيرة من القرويين منازل الأقباط. ألقوا الحجارة على البيوت، وحطَّموا الأبواب والنوافذ. أُضرِمت النيران في بعض الأراضي الزراعية المملوكة للأقباط. صرخت النساء مرارًا؛ وبكى الأطفال رعبًا. حتى أولئك الذين لا علاقة لهم بالعلاقة المزعومة تعرَّضوا للهجوم.”

كان غضب الحشد عشوائيًا، عقابًا جماعيًا يُفرَض بسبب انتهاك “الحساسيات الإسلامية”. ووفقًا لأحد التقارير، حوَّلت الهجمات مجتمعًا كان معتادًا على قدر معقول من التعايش إلى مجتمع يسيطر عليه الخوف. وصف السكان كيف تحوَّلت لحظات الحياة اليومية المشتركة—كاللعب المشترك للأطفال، وتبادل الزيارات بين الجيران—بلمح البصر إلى كراهية، وعدوان، ورعب.

استعادت الشرطة النظام في نهاية المطاف (بعد أن تشبَّع الحشد)، لكن الضرر—المادي والمعنوي—كان بليغًا. احتفظت الأسر المسيحية بأطفالها في المنازل ومنعتهم من الذهاب إلى المدرسة خوفًا من أن يتعرَّضوا للهجوم مرة أخرى. ويبحث العديد منهم الآن عن خيارات للانتقال من القرية.

قدَّم المسؤولون المحليون الوعود المعتادة: “يجب تطبيق القانون على الجميع”، صرَّحوا. ومع ذلك، يدرك المطلعون على وضع المنيا أن بيانات مماثلة قد أعقبت كل حادث مماثل تقريبًا، ونادرًا ما أدت إلى أي مساءلة.

إنَّ انفجار العنف في نزلة جلف ليس شذوذًا؛ بل هو الفصل الأحدث في نمط من العنف ضد المسيحيين في مصر يمتد لقرون. فمجرد اتهام بتجاوز الشريعة—التي تحظر العلاقات بين الرجال المسيحيين والنساء المسلمات—كان كافيًا لحشد الغوغاء المسلمين لفرض عقاب جماعي على الأقباط لما يقرب من أربعة عشر قرنًا.

تتمتع المنيا نفسها بسجل حافل بمثل هذه الحوادث. ففي العقود الماضية، استهدفت جماعات إسلامية متشددة مثل الجماعة الإسلامية الأقباط. واليوم، حتى في غياب التنظيم المسلح، لا يزال منطق الذنب الجماعي قائمًا: إشاعة عن رجل مسيحي تتحوَّل إلى تبرير لترويع عائلته بأكملها، وبالتالي مجتمعه.

في الواقع، يماثل هذا العنف الأخير حالات شنيعة أخرى في المنيا. ففي عام 2016، جُرِّدت امرأة مسيحية مسنة، سعاد ثابت، علنًا من ملابسها، وضُرِبت، وبُصِق عليها، وطُوِّفت بها في شوارع قرية الكرم على يد مئات من الرجال المسلمين—وكان “ذنبها” الوحيد هو اتهام ابنها بالارتباط بامرأة مسلمة. وعلى الرغم من أن أدلة الفيديو وشهادات الشهود حدَّدت المهاجمين بوضوح، فقد تبرَّأوا.

علَّقت لاحقًا بقولها: “على الرغم من أنني قوية، فإنه يصعب عليَّ التحدث أحيانًا؛ أنا دائمًا أحارب دموعي وأنهار في بعض الأحيان.”

منطق العقاب الجماعي المتواصل

كمثال آخر، في يناير 2012، هاجم حشد يزيد عن ثلاثة آلاف مسلم المسيحيين في قرية بالإسكندرية لأن مسلمًا اتهم مسيحيًا بامتلاك “صور حميمة” لامرأة مسلمة على هاتفه.

بعد أشهر، شهدت قرية دهشور هجومًا واسع النطاق آخر على الأقباط بعد أن أحرق كواء مسيحي قميص مسلم عن طريق الخطأ. اندلعت مشاجرة، وردًا على ذلك، هاجم حوالي ألفي مسلم منازل وأعمال تجارية مسيحية متعددة، مما تسبب في أضرار واسعة للممتلكات وأجبر عشرات الأسر على الفرار.

تُظهِر كل هذه الحوادث المنطق الدائم، الذي تم تحديده لأول مرة في شروط عمر، وهو نص فقهي رئيسي يحدد العلاقات بين المسلمين والمسيحيين: إساءة “ذمي” واحد تبرر العقاب الجماعي لمجتمع مسيحي بأكمله—وهو نمط يتكرر عبر القرون.

بالنسبة للحشد المسلم، فإن “الانتهاك” المزعوم ليس مسألة خاصة بل هو انتهاك للنظام الإلهي والاجتماعي. أوضح شهود العيان في هذا الهجوم الأخير في نزلة جلف ذلك: “حتى الأشخاص الذين لا علاقة لهم بالشخص المتهم تعرَّضوا للاعتداء. كان العنف عشوائيًا. أُضرِمت النيران. دُمِّرت المنازل. كانت النساء والأطفال يصرخون طلبًا للمساعدة.”

تجدر الإشارة إلى أن العديد من هذه الهجمات تحدث في أيام الجمعة—يوم الصلاة الجماعية للمسلمين—حيث غالبًا ما تثير الخُطب والتجمعات في المساجد غضب المصلين إزاء “التجاوزات” المتصوَّرة من قبل غير المسلمين. يضمن التعزيز الأيديولوجي، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الأعراف الاجتماعية الراسخة، أن العقاب الجماعي ليس مجرد أمر مُتسامح معه بل مُتوقَّع.

وهكذا، فإن إشاعات عن رجل مسيحي يغازل امرأة مسلمة، أو نزاعات بسيطة، تصبح كافية لتحريك حشد يرى نفسه ينفذ العدالة الإلهية—كما حدث عندما هاجم آلاف المسلمين وأحرقوا ممتلكات مسيحية في قرية أخرى بمحافظة المنيا عند علمهم بأن أسرة مسيحية على وشك تركيب مُقوِّي شبكة محمول على سطح منزلها.

باختصار، يتبع الانفجار الأخير في نزلة جلف سيناريو معروفًا جيدًا:

تظهر إشاعة أو اتهام، غالبًا ما يكون عن مسيحي “يتجاوز” حدوده ويجرح الحساسيات الإسلامية (عن طريق مواعدة امرأة مسلمة، أو محاولة بناء أو ترميم كنيسة، إلخ).

يتجمع حشد مسلم، مدفوعًا بمفاهيم الشرف والالتزام الديني الجماعية.

تُهاجَم منازل وممتلكات الأقباط؛ وتُروَّع النساء والأطفال.

تتدخل السلطات متأخرة، وتستعيد نظامًا سطحيًا لكنها نادرًا ما تعاقب الجناة.

يُجبَر المسيحيون على “المصالحة” مع مهاجميهم، دون رؤية أي عدالة تُطبَّق، ويستعدون للمرة التالية التي يتكرر فيها هذا النمط.

يؤدي الفشل في معاقبة الجناة إلى اعتقاد بأن مثل هذه الأفعال مقبولة. إن الإفلات من العقاب، المعزَّز على مر الأجيال، يُطبِّع العقاب الجماعي. في كل حالة من حالات العقاب الجماعي للأقباط، ينطبق المنطق نفسه—ولقرون: إشاعة + الشريعة الإسلامية + تطبيق متساهل للقانون = عنف غير مُقيَّد.

السيناريو قديم، ومألوف، وغير منقطع—وسوف يعيد التاريخ نفسه طالما بقيت الظروف كما هي.