كيف يهدد الجشع مسيحيي الشرق الأوسط

قراءة في خلفيات وأسباب مصادرة السلطات المصرية ملكية دير سانت كاترين للروم الأرثوذكس في جبل سيناء وأعلانه ملكاً للدولة.

ألبرتو إم. فرنانديز/ناشيونال كاثوليك ريجستر / 04 حزيران 2025

(ترجمة إلى العربية بحرية بواسطة إلياس بجاني، بالاستعانة بمواقع ترجمة إلكترونية)

How Greed Threatens Middle East Christians

An Analysis of the Background and Motives Behind the Egyptian Authorities’ Seizure of Saint Catherine’s Greek Orthodox Monastery in Mount Sinai and Its Declaration as State Property

Alberto M. Fernandez/National Catholic Register/June 04/2025

COMMENTARY: Power politics of the rich and numerous against the dwindling and powerless is very much at play.

Among the earliest remarks by Pope Leo XIV were expressions and concern for the Christians of the East. Less than a week after his election as Supreme Pontiff, he spoke at the Jubilee of the Oriental Churches of the “abyss of violence” that threatens Christian existence in those ancient regions of the faith, “from the Holy Land to Ukraine, from Lebanon to Syria, from the Middle East to Tigray and the Caucasus.”

Certainly, terrorism, religious hatred and violence are bitter realities for Eastern Christians, but other pressing threats may be more insidious.

The Pope spoke of the need for Middle East Christians to “persevere and remain in their homelands, resisting the temptation to abandon them.” This is not a hypothetical or future risk but a daily reality, for example, for Gaza’s beleaguered Catholics and Orthodox Christians — alive, battered and wounded — to try to remain in an urban landscape where most of what they see seems to be reduced to rubble.

Despite the rhetoric in the Gaza war, it is unlikely that Christians were ever targeted directly, and yet, like Muslims and Jews, they have borne a heavy price.

Persecution and martyrdom get the headlines, but while they are real, a more omnipresent, far more common threat appears, associated not so much with religious hatred as with greed — and with the power politics of the rich and numerous and against the dwindling and powerless.

From Egypt to Iraq, Christian property is under assault. It’s not personal; it’s just business.

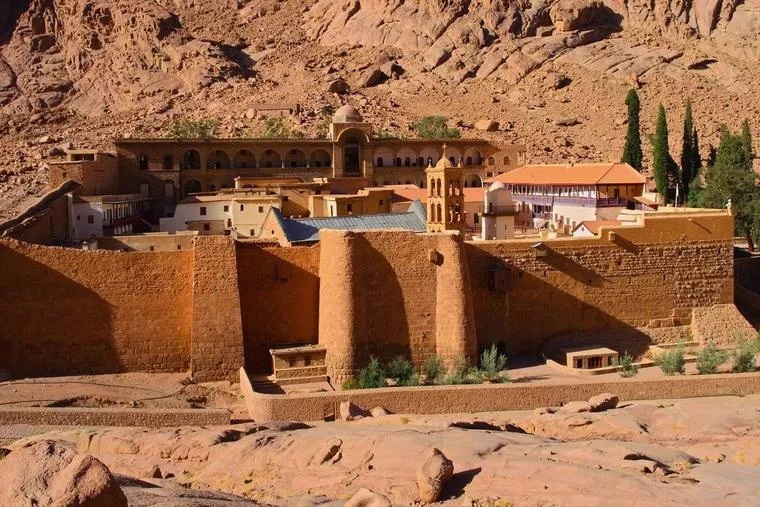

On May 29, Greek newspapers blared that the Egyptian government had seized St. Catherine’s Greek Orthodox Monastery on Mount Sinai and declared it state property. While online commentators were quick to portray it as some sort of Muslim, anti-Christian action shutting the monastery, the reality was much more mundane. This was more about real estate than persecution, eminent domain rather than religious hatred, involving a 10-year legal case by local officials.

Egyptian authorities, eager for income, see St. Catherine’s as a potential money maker, promoting religious and cultural tourism, which would complement Sinai’s splendid beaches. The danger to the monks seems to be more that they will be “Disney-fied” and marketed rather than expelled. The monastery, founded by Emperor Justinian the Great and once the site of the famed Codex Sinaiticus, one of the oldest, most complete copies of the Bible, is to be part of a larger tourist attraction. The sacred mountain seems to be more at risk from developers rather than jihadists.

In the Old City of Jerusalem, the historic Armenian Quarter is threatened less by religious hatred than by a shady deal with what Armenians consider unscrupulous real estate developers, who claim to have a valid 98-year lease on 25% of the Armenian Quarter. As in the case of Sinai, the ultimate goal seems to be profit and greed rather than hatred. But Christians rightly feel hemmed in by forces more powerful than them seeking to exploit what little remains in their hands.

Christian populations are dwindling throughout the region, but one thing that they still have is land, often empty land, which, coupled with zero to no political clout, makes for an enticing target. Neither Egypt nor Israel are particularly anti-Christian states, but they have more than their share of cutthroat businessmen.

Much Christian real estate in the Middle East is waqf land, religious endowments generally protected from seizure. In Islamic law, which is where waqf comes from, this land cannot be sold or transferred. It is for the use of the religious community.

Such land used for commercial or rental purposes should generate income for the local church or mosque. But, of course, holding on to the land is only as good as the will of the lawyers, judges and the state to protect private property owned by religious minorities. In post-Assad Syria, at least some of the tensions in early 2025 between Christians and Muslims has been over property rights.

Not all of the Christian real-estate land-grab news has been bad over the past years. In Turkey’s historic Tur Abdin region, after many years of turmoil, litigation, village rivalries and high-level international attention, the fourth-century Syrian Orthodox Mor Gabriel Monastery recovered its land in a 2014 decision hailed as “the largest restitution of church property ever seen in Turkey.” The ruling was part of Turkey’s democratization process at the time overseen by the prime minister, now president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

While Turkey was a rare positive light, the land grab against Christian property in Iraq continues to be a concern. Christians being displaced or fleeing the country have found their land being taken by political parties, militias and connected individuals. Records are falsified and deeds doctored, and even waqf land has not been immune. It isn’t outright persecution per se but merely the strong preying on the weak.

A Justice Ministry official told the Al-Arabi al-Jadeed newspaper in February 2025 that “the file is still complicated, and the ministry is making every effort to return Christian property and provide protection for it through strict measures.”

Impoverished Middle East Christians, disinherited ones, Christians tied up in years of agonizing litigation against the powerful are, of course, far less like to stay in their ancient homelands, less likely to put down roots when the very land is taken away from them.

While we focus on the very real, often violent, persecution of Christians in the East, let us not forget the all-too-silent, gradual usurpation of their rights as full citizens, rights to be secure in their persons, their faith and their property.

**Alberto M. Fernandez Alberto M. Fernandez is a former U.S. diplomat and a contributor at EWTN News.

https://www.ncregister.com/commentaries/how-greed-threatens-middle-east-christians

كيف يهدد الجشع مسيحيي الشرق الأوسط

قراءة في خلفيات وأسباب مصادرة السلطات المصرية ملكية دير سانت كاترين للروم الأرثوذكس في جبل سيناء وأعلانه ملكاً للدولة.

ألبرتو إم. فرنانديز / ناشيونال كاثوليك ريجستر / 04 حزيران 2025

(ترجمة إلى العربية بحرية بواسطة إلياس بجاني، بالاستعانة بمواقع ترجمة إلكترونية)

تعليق: سياسات القوة التي يمارسها الأغنياء والأكثريات الدينية ضد الأقليات والمستضعفين هي في صميم المشهد.

من بين أولى الملاحظات التي أدلى بها البابا فرنسيس بعد انتخابه، كانت تعابيره واهتمامه بالمسيحيين في الشرق. فبعد أقل من أسبوع على انتخابه حبراً أعظم، تحدث في يوبيل الكنائس الشرقية عن “هاوية العنف” التي تهدد الوجود المسيحي في تلك المناطق العريقة بالإيمان، “من الأراضي المقدسة إلى أوكرانيا، ومن لبنان إلى سوريا، ومن الشرق الأوسط إلى تيغراي والقوقاز”.

بالتأكيد، الإرهاب والكراهية الدينية والعنف هي حقائق مريرة بالنسبة للمسيحيين الشرقيين، ولكن قد تكون التهديدات الأخرى، الأكثر إلحاحًا، أكثر دهاءً وخفاءً.

تحدث البابا عن حاجة مسيحيي الشرق الأوسط إلى “المثابرة والبقاء في أوطانهم، ومقاومة إغراء التخلي عنها”. وهذا ليس مجرد خطر افتراضي أو مستقبلي، بل واقع يومي، على سبيل المثال، بالنسبة للكاثوليك والأرثوذكس المحاصرين في غزة — أحياء، متضررين وجرحى — يحاولون البقاء في مناطق مدنية يبدو أن معظمها قد تحول إلى أنقاض.

ورغم ما يُقال في سياق حرب غزة، فمن غير المرجح أن يكون المسيحيون قد استُهدفوا بشكل مباشر، ومع ذلك، فقد دفعوا ثمناً باهظاً، شأنهم شأن المسلمين واليهود.

إن الاضطهاد والاستشهاد يتصدران العناوين، لكن في حين أن هذه الوقائع حقيقية، هناك تهديد آخر أكثر انتشارًا، لا يرتبط بالكراهية الدينية بقدر ما يرتبط بالجشع — وبسياسات القوة التي يمارسها الأغنياء والأكثريات (الدينية) ضد الأقليات والمهمشين.

من مصر إلى العراق، تتعرض ممتلكات المسيحيين لهجمات ممنهجة. الأمر لا يبدو شخصيًا؛ بل “مجرد عمل تجاري”.

في 29 أيار، تصدرت الصحف اليونانية أنباء تفيد بأن الحكومة المصرية استولت على دير سانت كاترين للروم الأرثوذكس في جبل سيناء وأعلنته ملكاً للدولة. وبينما سارع المعلقون عبر الإنترنت إلى تصوير الأمر على أنه عمل إسلامي معادٍ للمسيحية يهدف إلى إغلاق الدير، كانت الحقيقة أكثر بساطة وواقعية. الأمر كان يتعلق بالعقارات أكثر منه بالاضطهاد، وبالاستيلاء العام أكثر منه بالكراهية الدينية، وهو نتيجة دعوى قضائية استمرت عشر سنوات رفعها مسؤولون محليون.

ترى السلطات المصرية، المتعطشة للدخل، أن دير سانت كاترين مصدر محتمل للأرباح، وتسعى لتشجيع السياحة الدينية والثقافية فيه، بما يُكمل جاذبية شواطئ سيناء. ويبدو أن الخطر الذي يواجهه الرهبان يتمثل في أنهم سيتحولون إلى “عرض ديزني” يتم تسويقه بدلًا من طردهم. الدير، الذي أسسه الإمبراطور جستنيان العظيم وكان في السابق موطنًا للمخطوطة السينائية الشهيرة — إحدى أقدم وأكمل نسخ الكتاب المقدس — أصبح جزءًا من مشروع سياحي أكبر، ويبدو أن الخطر على الجبل المقدس يأتي من المطورين العقاريين لا من الجهاديين.

وفي نفس السياق وفي البلدة القديمة بالقدس، يواجه الحي الأرمني التاريخي تهديدًا لا من الكراهية الدينية، بل من صفقة عقارية مشبوهة مع من يعتبرهم الأرمن مطورين عقاريين عديمي الضمير. هؤلاء يزعمون امتلاكهم عقد إيجار صالح لمدة 98 عامًا على 25% من الحي الأرمني. وكما في حالة سيناء، يبدو أن الدافع هو الربح والجشع لا الكراهية، لكن المسيحيين يشعرون — عن حق — أنهم محاصرون بقوى أقوى منهم تسعى لنهب ما تبقى في أيديهم.

إن أعداد السكان المسيحيين تتناقص في كل أنحاء المنطقة، لكن ما يزال لديهم شيء واحد ثمين: الأرض، وغالبًا ما تكون أراضي غير مستثمرة. ومع نفوذ سياسي معدوم أو ضعيف، تصبح هذه الأرض هدفًا مغريًا. لا مصر ولا إسرائيل دولتان معاديتان للمسيحيين بشكل منهجي، لكن فيهما ما يكفي من رجال الأعمال عديمي الرحمة.

الكثير من الممتلكات المسيحية في الشرق الأوسط هي أراضي وقف، وهي أوقاف دينية محمية من المصادرة عمومًا. ففي الشريعة الإسلامية، مصدر نظام الوقف، لا يمكن بيع أو نقل هذه الأرض، وهي مخصصة لخدمة المجتمع الديني.

ينبغي أن تولد هذه الأراضي، إذا تم استثمارها تجاريًا أو تأجيرها، دخلاً للكنيسة أو المسجد المحلي، لكن الاحتفاظ بهذه الأراضي يعتمد كليًا على إرادة المحامين والقضاة والدولة في حماية حقوق الأقليات الدينية. في سوريا ما بعد الأسد، برزت في أوائل عام 2025 توترات بين المسلمين والمسيحيين بشأن حقوق الملكية.

رغم كل شيء، لم تكن جميع أخبار الاستيلاء على الممتلكات المسيحية سلبية، ففي منطقة طور عابدين التاريخية بتركيا، وبعد سنوات من الدعاوى والصراعات القروية والاهتمام الدولي، استعاد دير مار جبرائيل السرياني الأرثوذكسي، الذي يعود للقرن الرابع، أراضيه في قرار صدر عام 2014 ووُصف بأنه “أكبر ردّ لممتلكات كنيسة في تاريخ تركيا”. جاء هذا القرار ضمن جهود دمقرطة تركيا في تلك المرحلة تحت إشراف رئيس الوزراء، والرئيس الحالي، رجب طيب أردوغان.

لكن تركيا تبقى استثناء نادراً، ففي العراق، لا تزال عمليات الاستيلاء على ممتلكات المسيحيين مصدر قلق كبير. فالمسيحيون الذين نزحوا أو فروا من البلاد اكتشفوا أن أراضيهم تم الاستيلاء عليها من قبل أحزاب سياسية وميليشيات وأفراد مرتبطين بها. يتم تزوير السجلات والصكوك، بل وحتى أراضي الوقف لم تسلم. هذا ليس اضطهادًا مباشرًا بقدر ما هو استغلال القوي للضعيف.

في شباط 2025، صرح مسؤول بوزارة العدل لصحيفة “العربي الجديد” قائلاً: “الملف لا يزال معقدًا، والوزارة تبذل قصارى جهدها لإعادة الممتلكات المسيحية وتوفير الحماية لها من خلال إجراءات صارمة”.

المسيحيون الفقراء والمحرومون، والذين عانوا لسنوات من التقاضي المؤلم ضد الأقوياء، هم بطبيعة الحال أقل قدرة على البقاء في أوطانهم، وأقل رغبة في ترسيخ جذورهم حين تُسلب منهم الأرض ذاتها.

وبينما يتم التركيز على الاضطهاد العنيف والصريح الذي يطال المسيحيين في الشرق، فلنتذكّر أيضًا الاغتصاب الصامت والبطيء لحقوقهم كمواطنين متساوين، وحقهم في أن يكونوا آمنين في أشخاصهم، وإيمانهم، وممتلكاتهم.

ألبرتو إم. فرنانديز

دبلوماسي أمريكي سابق، وكاتب مساهم في “EWTN News”