الجمود الإسرائيلي الفلسطيني….لم يكن ترامب أول من أدخل الترحيل العربي في الحوار السياسي

بقلم مردخاي نيسان/مجلة نيو إنكلش ريفيو/02 آذار/2025

(ترجمة غوغل والياس بجاني بحرية مطلقة)

The Israeli-Palestinian Impasse…Trump was not the first to introduce Arab transfer into the political conversation

by Mordechai Nisan/New English Review/March 02/ 2025

Zionism and the Arabs

Moshe Smilansky, a founder of Rehovot in 1890, became intimately familiar with Arabs in the country. He contended in his essay Be-Moledet (The Homeland) in 1915 that, the Arab would succumb “if he senses you have power … and maintain his hatred for you in his heart.” Facing a harsh reality, the dreaded sea and its waves, there was no alternative to “jumping into the sea, and blessed be that jump for all times.”

Yitzhak Epstein, an educator in the Galilee, pondered the Arab question in his lecture The Hidden Question from 1907. Epstein warned that the Arab is rooted in the land and bound to his village; and he will not gingerly leave when Jews purchase the land where he tills the soil, wander elsewhere, abandoning the graves of his fathers.

Yosef Haim Brenner, a noteworthy author, came to the homeland arriving in Haifa in 1909. Brenner lamented when immediately encountering Arab youth: “Hatred between us [Jews and Arabs] – already exists and will exist.” His was a bitter prognosis for the future of Zionism. Brenner’s own future ended when brutally murdered by Arabs in Jaffa in 1921.

Zev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism, explained in his essay The Iron Wall in 1923, that there was no possibility that Arabs would voluntarily accommodate Zionism: “there has never been an indigenous inhabitant anywhere or at any time who has ever accepted the settlement of others in his country.” Zionism needs, figuratively but perhaps also literally, an iron wall which the native population cannot break through.”

Arthur Ruppin headed settlement activities in the Galilee after arriving to Jaffa in 1908. Cognizant of obstacles on the path of Zionism, he questioned in his diary entry from January 12 whether in the long term “Zionist aspirations will be regarded as the beginning of an important historic movement or as a fantastic stupidity.” He perceived the Arabs as the biggest problem, with no hope for genuine reconciliation between the two peoples.

Shmuel Yosef Agnon, renowned Nobel-prize author, lived in the Talpiot neighborhood of Jerusalem when the countrywide Arab bloodbath burst out in 1929. He confided to his patron-publisher S. Z. Schocken: “Since the days of the riots my attitude to the Arabs had changed. My attitude is now this: I don’t hate them and I don’t love them, all I want is not to see their faces.” Separation from the Arabs was the optimal choice for the Jews.

War and the Transfer Idea

In April 1920, the Nebi Musa riots in Jerusalem left nine Jews dead and over two hundred injured; in the 1921 Jaffa riot 47 Jews were murdered; and in the pogroms of 1929—in Hebron, Jerusalem, and elsewhere—133 Jews met their brutal death. The Arab Revolt of 1936-39 accounted for approximately 500 dead Jews. British authorities concluded that Zionism was an unsettling provocation and threat to the Arab population.

The idea of Arab emigration, expulsion, or transfer surfaced in Zionist circles. Inter-communal clashes, notoriously initiated by the Arab side, signaled that the presence of two rival peoples in one tiny country was a prescription for tension and war.

Theodor Herzl, the political founder of Zionism, was an early advocate for propelling Arab migration from Palestine. His diary entry from June 12, 1895, was revelatory: “We shall try to spirit the penniless [Arab peasant] population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries whilst denying it any employment in our own country.” This was a paradigmatic formula to incentivize Arab transfer through economic measures, without the use of force.

David Ben-Gurion, later Israel’s first Prime Minister, did not shy away from the transfer of Arab tenant farmers relocating from Western Palestine to Transjordan across the river. In 1937, when the British Peel Commission recommended the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state, it also proposed the transfer of over 200,000 Arabs to the Arab state. It concluded that for Jews and Arabs “within the narrow bounds of one small country…there is no common ground between them. Their national aspirations are incompatible.” The Peel Report recognized “the gulf is wide and will continue to widen.” Ben-Gurion enthusiastically endorsed the possibility of an Arab transfer to Transjordan, or Syria and Iraq.

Berl Katznelson, the conscience of the Labor Movement, believed moreover that transfer “is the best of solutions … this must take place one of these days.” He intended Arab transfer, not to nearby Nablus, but echoing Ben-Gurion to Syria and Iraq.

Yosef Weitz, who headed the Jewish Settlement Department in pre-state years, left the following diary entry in 1940 (quoted in Davar, September 29, 1967): “…it must be clear that there is no room in this country for both peoples. The only solution is Eretz-Israel, at least the Western Israel, without Arabs, and there is no other way but to transfer the Arabs from here to the neighboring countries—to transfer them all—not one village, not one tribe should be left.” This radical program of ethnic cleansing enabled Weitz to confront the elephant in the room.

Chaim Weizmann, to be Israel’s first President, opposed transfer through coercion in an article in Foreign Affairs in January 1942. He presumed that Muslims would prefer to evacuate rather than live under an “infidel” Jewish regime.

In 1947, the Arabs rejected the United Nations Partition Resolution and fighting which they initiated raged throughout the country. Arabs fled from Tiberius and Haifa in April of 1948. After the IDF captured Lod in July, Ben-Gurion visited the area and motioned to senior army officers Yigal Allon and Moshe Dayan with a wave of his hand to expel the Arab inhabitants. Fear of living under Jewish rule, yet hope for a final Arab victory, impacted decisively upon thousands of departing inhabitants.

By the end of Israel’s War of Independence, about a half a million Arabs took flight and became refugees. In cases where Jews entreated Arabs to endure the situation and remain, they nonetheless packed their belongings as in Haifa and left the country. Benny Morris concluded in The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, that the Arab exodus “had solved the embryonic Jewish state’s chief and agonizing political-strategic problem, the existence in it of a very large actively or potentially hostile Arab minority.”

Moshe Sharett, Israel’s first Foreign Minister, confessed to Weizmann in July 1948, that Arab flight from the fledgling state was an opportunity: “We are determined … to explore all possibilities of getting rid, once and for all, of the huge Arab minority which originally threatened us.”

Alec Kirkbride, senior adviser to the government of Transjordan in the 1920s, understood the path to conflict-resolution. He revealed in his autobiography that the British intended the area east of the river “to serve as a reserve of land for use in the resettlement of Arabs once the National Home for the Jews in Palestine, which they were pledged to support, became an accomplished fact.”

Leopold Amery, a member of the British cabinet dealing with Palestine, addressed a letter to Prime Minister Churchill in 1941: “Taking a long view the ideal policy might be to give the Jews the whole of Palestine and find the money for the transference of the existing Palestinian [Arab] population to Transjordan and Syria and its resettlement there.”

Reality caught up with Kirkbride and Amery during the years from 1948 to 1967. Approximately 250,000 Arabs—one-third of the population—migrated eastward from the West Bank to Amman, Salt, Zarka, and other Jordanian towns. This served as a temporary station for a sizable number who resettled in Kuwait, Chile, Germany, and the United States.

Edward Norman, an American philanthropist, proposed in the 1930s the resettlement of Palestinian Arabs in Iraq. The agricultural potential of Mesopotamia, filled with the waters of the Euphrates valley, could easily support a large Arab immigration. Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt had both expressed their agreement with transfer. John Gunther in his book Inside Asia considered that “something drastic must be done” in the conflict-ridden Palestine arena, mentioning the Turkey-Greece population exchange after World War I as a model to separate the warring protagonists in Palestine one from the other.

Insightful observers who had met with Herzl and aware of his Jewish state idea predicted a violent outcome, which in fact occurred in the 1948 War. Sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz mused on Herzl’s naiveté: “You want to create a state without bloodshed? Where have you ever seen such a thing? Without force and without cunning?” Sidney Whitman, an Englishman familiar with the East, magnified the Zionist quandary: “How, without dispossessing the natives [Arabs], would the Jews obtain the land they needed?” Jews would have to re-enter history with a sword in their hands.

George Antonius, employed by the British administration in Palestine, concluded in The Arab Awakening from 1938: “There is no room for a second nation in a country which is already inhabited … it is not possible to establish a Jewish state in Palestine without the forcible dislodgement of a peasantry who seem readier to face death than give up their land.” The First Arab-Israeli War in 1948 partially confirmed Antonius’s grim prognosis.

Arabs in Israel

Within the renewed Jewish state of Israel in 1948, there remained an Arab minority numbering nine per-cent of the total population, escalating to some twenty per-cent by 2025. Of the two million non-Jews seventy-five per-cent were Muslims. Israel therefore acquired the character of a Jewish-Muslim country or a Jewish-Arab country that compromised the essence of the Zionist ethos. Arab collective confidence soared, many identified as Palestinians, and many accentuated their Muslim faith. All the while, Arab citizens possess voting rights and liberty without the state demanding they fulfill obligations—neither military nor civilian service of any kind.

The Arabs in Israel experienced the benefits of life in the Jewish state. They enjoyed a state-financed Arabic-language educational stream and access to higher education entailing affirmative action criteria for Arab applicants. Job opportunities expanded over the years: nearly a third of Israel’s physicians, a quarter of the nurses, and half of the pharmacists, are Arabs. Israel’s brand of Jewish nationalism was not antithetical to accommodating a diversified and inclusive society.

Arab Knesset representation jumped from two in 1949 to 15 in 2015, dropping to 10 in 2022. Ninety-per cent of Arab voters support the three Arab parties. They all espouse the Palestinian narrative—bemoaning the ’48 Nakba catastrophe, denouncing Israel’s occupation in the post-’67 territories, and demanding an inherently irredentist Palestinian state beside Israel—all the while spouting grievances as victims of discrimination in Israel.

The Arab public, unlike the small Druze community, is decidedly anti-Zionist. Polling conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute found that more than half of the respondents reject the definition of Israel as a Jewish nation-state. Arabs do not identify with the Israel National Anthem, the Israeli flag, and Independence Day celebrations. Indeed, Independence Day is a mournful memory for the loss of Palestine, not forgiving, not forgetting. Popular folklore relates that Arab women, perhaps grandmothers of elderly women of today, would despondently say of Jews/Israelis: “Cursed are the boats that brought you here.

Arab university students in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa, protest on campuses against the Army, unfurling the Palestinian flag. This political ritual is the badge of Palestinian national sentiment in Jewish Israel. Arab citizens are notoriously prominent in crime and subversion in and against the state. Intra-Arab murders and Palestinian terror cells feature prominently. Interestingly, a report from November 2023 found that if offered citizenship in a western country, many Arabs—more than among Jews—would leave Israel.

Meanwhile, Arabs stay in Israel and parade their true political colors. In 2017, a delegation of Arab dentists from Israel attended a medical course in Bogota. Each foreign delegation sang its national anthem, but the ‘Israeli’ one refused to sing Hatikva, and chose a Palestinian Arab anthem instead. This outrageous behavior is of a piece with the call by Ra’ed Salah, heading the Islamic Movement in Israel, to hoist the flag of Islam on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

Former Member of Knesset Azmi Beshara, suspected of espionage for Hezbollah in the 2006 Second Lebanese War, provided a scandalous case of Arab disloyalty. He subsequently fled Israel to Qatar to escape interrogation and arrest.

Leading Arab agitators and instigators included parliamentarians Hanin Zoabi, Ayman Odeh, and Jamal Zahalka. MK Ahmed Tibi praised “martyrdom terrorism” and defined the Land of Israel as a [Zionist] colonial phrase. In a meeting with President Reuven Rivlin in 2019, he showed unflinching arrogance. Stating: “We [Arabs] did not immigrate here [unlike the Jews]. We are the owners of this land.”

Mahmoud Darwish, the soi-disant Palestinian national poet, had earlier depicted Jews in his poem “Identity Card” as strangers destined to go away: “So leave our country, our land, our sea … Everything and leave.”

Sample polling has examined the attitude of Jewish respondents toward Arab fellow-citizens. The Israel Democracy Institute found a majority of Jews favoring revoking Arab citizenship or denying them the right to vote and sit in the Knesset. This finding converges with another disclosure from a Dahaf poll from mid-November 2023, with half of the Jewish respondents feeling that relations between the two peoples had changed for the worse since the Iron Swords War began. As reported by the A Chord social-academic organization on March 24, 2024, only about half the Jews polled believe that Arab citizens oppose violence against Jews; and 64 percent of the Jews fear for their own safety, and with greater urgency after the massacre of October 7, 2023. The absence of trust cuts to the core of the Jewish-Arab impasse.

Raymond Aron, in his 1962 book Peace and War: A Theory of International Relations, could not have been more accurate: “Israelis and Palestinian Muslims [who are Israeli citizens] cannot form a single collectivity and cannot occupy the same territory: one or the other is doomed to suffer injustice.” Unless otherwise proven, the ideological deadlock is built-in and carved in stone.

Escalation and Expanding the Conflict

Beginning in 1967 an additional Arab population complicated and exacerbated the problem.

The inclusion within Israel of the Palestinians in Judea-Samaria [West Bank] and the Gaza Strip magnified the conflictual predicament between the two peoples. The Six Day War, which Israel won, burdened her with a large Palestinian community. Before the 1993 Oslo Accord and thereafter, Palestinian terrorism intensified throughout Israel: bus and restaurant bombings, car and truck rams, fire projectiles and gun shootings, stabbings and kidnappings—the gamut of ways to kill Israelis.

While demanding a Palestinian state, to implement the devious two-state solution, Palestinians aspired to the complete eradication of Israel. Faisal al-Husseini and Abu Iyad, among other nefarious PLO figures, advocated a single state solution with refugee return to forge a Palestinian majority. Indeed, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy published a report in July 2021 that found support for a two-state solution drop among Arabs with the rise of support for one state that could “reclaim all of Palestine.” The Arab Center Washington DC published an article by Samer Elchahabi “Shifting the Paradigm” in December 2023, proposing a single democratic state for Jews and Palestinians that would rent asunder the state of Israel.

Hamas, as the leading Palestinian rival to the Fatah-PLO movement, wrapped its war against Israel and the Jewish people in the Islamic idiom. The objective of Hamas as codified in Article Seven of its covenant is to kill the Jews, and fight to liberate Palestine as an Islamic Waqf land consecrated for Muslim generations until Judgment Day. Article 13 put on record that “there is no solution for the Palestinian question except through Jihad.”

The Koran calls upon Allah “to exalt Islam above all religions” (61:9) and “to help [the Muslims] overcome the nonbelievers” (2:286). It is this mission of Islam—inflamed by hatred of the Jews—that whipped up the Palestinians to invade and attack Israel, murder and rape, dismember and mutilate, burn babies in ovens and stab to death pregnant women on October 7, 2023. This Palestinian Nazi-like barbarism is the blackest stain on Islam in modern times.

The Failure of Co-Existence

Many are the examples of tension and violence in bi-national and poly-ethnic states, as plagued Yugoslavia, South Africa, Sudan, Syria, Iraq, and Rwanda. In past decades, forced expulsion was the fate of Turks in Bulgaria, Palestinians in Kuwait, Yemenis in Saudi Arabia, and Bosnians in Serbia.

Instances of societal escalation on religious or ethnic grounds terminate at times with demographic flight, expulsion, transfer, and population exchange. After the First World War, a consensual population exchange of two million people occurred from 1922-24 between Turkey and Greece; after the Second World War, and with the Allied Powers’ agreement, eight million Germans fled, migrated, or were expelled from Poland and Czechoslovakia. In war between India and Pakistan in 1947, 15 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs, fled across newly demarcated borders. In the same year over 400,000 Finns were driven from Russia and resettled in Finland. The Soviet Union forcibly transferred six million people in the years 1930-52. While hundreds of thousands of Arabs left Israel in 1948, a similar number of Jews fled Arab countries. In the 1980s, many thousands of Whites fled the insecurity of life in Zimbabwe and Zambia. Azerbaijan expelled one hundred thousand Armenians from the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave in the war of 2023 in the southern Caucasus. Since 2022 and Russia’s war against the Ukraine, six million Ukrainians left their country for Hungary and Poland and other destinations; another eight million were displaced within. Unrest and warfare in Afghanistan led to refugee flight of more than five million people to Iran and Pakistan. Fear and hope sometimes alternate or intertwine to trigger a flood of human displacement.

Economic motives have played a role in encouraging migration. More than three million Indians sought work in the United Arab Emirates. Mass Muslim migration from Africa, the Middle East, and southern Asia swamped Europe. A reckoning with illegal immigration to America is a central pillar in President Trump’s program in the years ahead.

Promoting Emigration

Yitzhak Rabin, IDF Chief-of-Staff and later Israel’s Prime Minister, proposed in an interview with the Israeli newspaper Ma’ariv on February 16, 1973 a solution for Gazan refugees on the East Bank of the Jordan: “We [Israel] can bring about a population movement [of Arabs] on a basis other than through the use of force. I want to create conditions such that…there will be a natural population migration to the East Bank.” Speaking on BBC TV on May 1 the same year, Moshe Dayan was blunt: “Israel should remain for eternity and until the end of time in the West Bank … If Palestinians didn’t like this they could go and establish themselves in an Arab country.” Writing in Breakthrough, Dayan, like Rabin, believed Jordan to be the optimal and proximate destination for Palestinian refugees. Jordan was already the home to a Palestinian-majority population.

On June 26, 2023, the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research published the Arab Barometer Poll, finding that more than one-third of the Gazans and 20 per-cent of the West Bankers were considering emigrating to Turkey, Germany, Canada, and the United states, in search of economic and educational opportunities.

In February 2024, Israeli researchers Noga Arbel and Yoav Sorek outlined a plan for “Voluntary Emigration” to facilitate Gazan refugees, facing the harsh reality of the massive damage and destruction of houses and infrastructure in the war, to seek resettlement elsewhere. Transfer by consent sounds like turning a punishment into a reward.

The subject of transfer can also turn in the opposite direction. Yasser Arafat had predicted that the time would come when the Israelis will flee Palestine. He shared his hope in July 1985 with journalist Abdul Bari Atwan that he, Atwan, will live to see the day when “the Israelis would flee like rats from a sinking ship” (MEMRI, Aug. 19, 2021). Under the vice of Palestinian warfare, a frightened and demoralized Israeli society would collapse. Refugee return will usher in the demographic subversion of Jewish Israel.

Findings published in January 2025 from a global survey commissioned by the ADL (Anti-Defamation League) illustrate the profound Arab hatred of Jews blazoned across Palestinian political skies. Among all peoples and places regarding anti-Semitic attitudes, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip Palestinians ranked first in the world with a figure of 97%. In Sweden it was 5% and in Canada 8%. No country wants neighbors holding such abhorrent feelings just next door across the border. A popular refrain in Palestinian society was the rhythmic Arabic mantra Filastin biladna wa al-Yahud kilabna (Palestine is our land and the Jews are our dogs). The myth of a Palestinian peace partner fades away.

Toward a Solution

Admittedly, there are daily Jewish–Arab relations and interactions on various levels in Israeli society. Co-existence takes place in work environments and in mixed towns. This humanizes an otherwise conflictual situation; yet this piece of reality is nothing more than of local, anecdotal, personal and non-political significance.

Israeli government policies could create conditions to spur Arab citizens to pack up and leave:

In the economic field—enforcing strict tax collection.

In the security field—collecting illegal weapons.

In the cultural field—canceling affirmative action in higher education.

In the linguistic field—limit public, official, and transportation signs to the Hebrew and English languages.

In the political field—forbidding candidacy in elections to supporters of terrorism and deniers of a Jewish state.

In the social field—imposing mandatory civilian national service.

These non-violent measures are reasonable and equitable in a democratic state, accounting especially for Israel’s particular character and circumstances.

Israeli measures to promote migration eastward are doubly important regarding the Arab population in Judea and Samaria, and the Gaza Strip. Palestinians have conducted a savage terrorist war against Israeli soldiers and Jewish settlers. Parading their weapons marching through Jenin in northern Samaria, with high profile exposure and chanting jihad-like slogans, is a 2025 Palestinian nightmarish reality.

The Arabs in Israel are vulnerable and walking on thin ice. They who actively operate to push the Jews out may ultimately find themselves in the dialectic twist as victims of their own demonic designs. The Arabs have forced Israel’s hand, in 1948, somewhat in 1967, partially in 2024 within Gaza. Have they learned any lesson from the past?

Until President Trump dropped his political bomb proposing to relocate Gazan Arabs out of the country, transfer was a taboo subject. Incessantly maligned was anyone who dared mention transfer, though in the past the politically mainstream Herzl, Katznelson, Sharett, Weizmann, Ben-Gurion, and Rabin, advocated in varying configurations and formulations this very idea. The idea is sound regardless of who gives voice to it.

Table of Contents

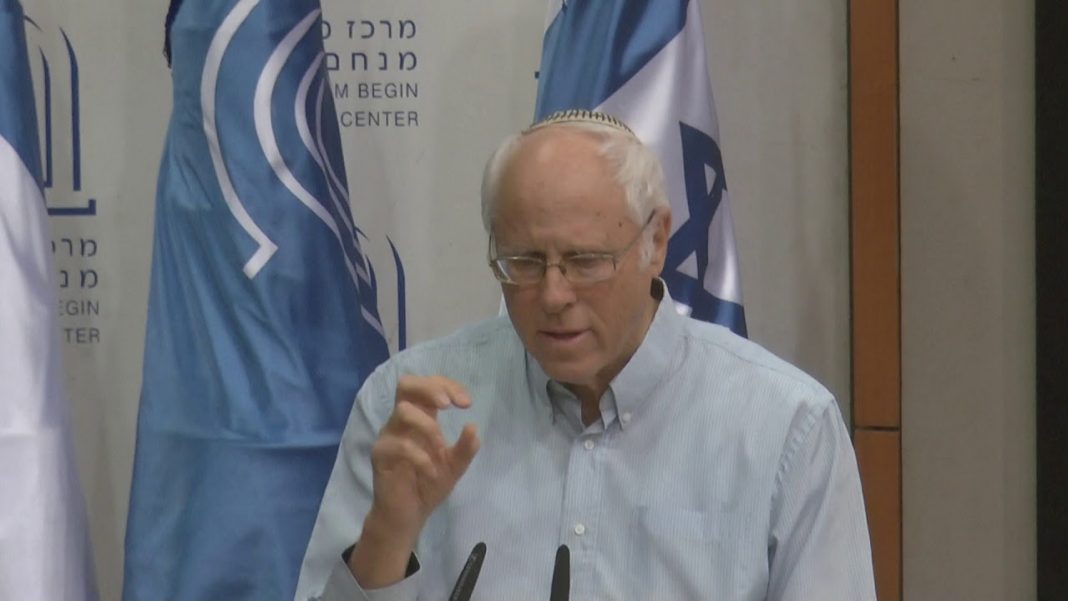

Mordechai Nisan is a retired lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He also taught at Bar-Ilan University, the Open University, and the pre-army Lachish academy at Beit Guvrin. Among his books: Minorities in the Middle East, Toward a New Israel, The Crack-up of the Israeli Left, The Conscience of Lebanon, and Identity and Civilization.