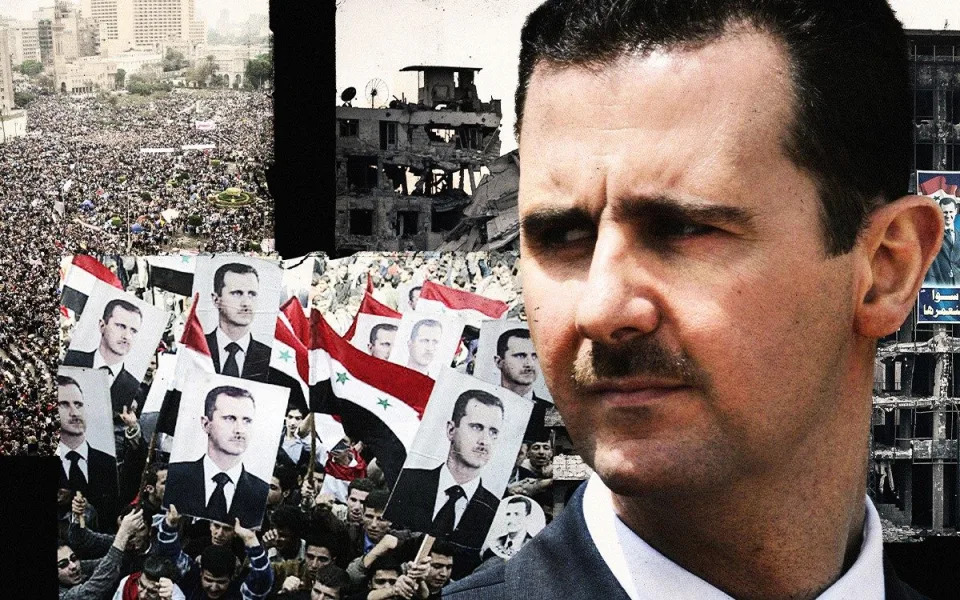

Is the world really ready to rehabilitate Bashar al-Assad?

Con Coughlin/The Telegraph/Wed, June 21, 2023

هل العالم جاهز حقًا لإعادة تأهيل بشار الأسد؟

كون كوغلين/التلغراف/ الأربعاء 21 حزيران 2023

Since Bashar al-Assad took power, Syria has seen over a decade of civil war and the tyrannical suppression and murder of its people. Yet recent overtures suggest a sudden shift in international attitudes to the dictator.

When I first began writing about the Middle East for The Daily Telegraph in the early 1980s, I experienced not so much a baptism of fire, but a coming under fire in every sense.

Back then there were none of the hazardous-environment courses that foreign correspondents these days undergo before travelling abroad. The only requirements for covering war zones were basic reporting skills and an appetite for adventure.

Prior to arriving in war-torn Beirut in 1983 at the height of the country’s brutal civil war, my only previous experience of unrest was covering the Brixton riots in 1981 which, while violent, hardly counted as warfare.

Immediately before flying into Beirut’s battered airport, I had spent a bewildering few weeks writing about America’s military invasion of the delightful Caribbean island of Grenada.

During my three-week sojourn in St George’s, the capital, the only hazards to my well-being were the large clouds of cannabis smoke that accompanied Hunter S Thompson, the high priest of gonzo journalism, who was covering events for Playboy magazine.

Beirut was a different proposition altogether. I was 28, and had a burning desire to prove myself by undertaking front-line assignments in some of the world’s most demanding war zones. Lebanon’s civil war, which dated back to 1975, fitted the bill perfectly.

The US Marine Corps detachment that had invaded Grenada had been sent to relieve the American Marine detachment in Beirut, which had just suffered 241 dead and hundreds more injured after their barracks were blown up by a new Lebanese militia called Hizbollah.

As I had already become acquainted with the Marines in Grenada, my Telegraph bosses thought it made sense for me to accompany them to Lebanon. And so began my long involvement with the region, where during the next decade I came under fire on numerous occasions and narrowly escaped being kidnapped by Islamic militants.

To say I was unprepared to deal with such dangers is an understatement. On one of my first nights in Beirut I ventured into the southern suburbs to investigate reports of a tank battle between rival militias only to find myself being caught up in the fighting and having to run for cover. In those days foreign correspondents did not enjoy the luxury of flak jackets and protective helmets: you were literally expected to survive on your wits.

Gradually, I became more street smart. When the shelling around my hotel was particularly intense, I took to sleeping in the bath as protection against shrapnel fragments. And when the militiamen began kidnapping British journalists, such as my colleague John McCarthy, I made a hasty escape by hiding under a blanket on the back seat of a taxi to Beirut airport, where I managed to catch one of the last flights out to Cyprus and safety.

It was during this tumultuous period in my four decades-long Telegraph career that I developed an abiding interest in the Middle East, and especially the menacing shadow the Assad regime in Syria has cast over the region since the late president Hafez al-Assad seized power in a coup in 1970.

As a close ally of Iran, Assad was deeply involved in the Lebanese civil war: Syrian intelligence had been implicated in the bombing of the US Embassy and Marine compounds in 1983. My coverage was highly critical both of the Assad regime and Hizbollah – its main ally in Lebanon.

As a consequence, I soon discovered that not only had I been banned from travelling to Syria; my name had been added to Hizbollah’s hit list of Western targets.

After Syria became the latest repressive Arab state to fall victim to a brutal civil war in 2011, my focus turned to the role of Bashar al-Assad in the conflict. Having inherited the residency from his father, the shy and retiring Bashar had managed to turn himself into one of the most reviled dictators of the modern age.

Throughout the course of the Syrian conflict, Bashar was to be found at the heart of his regime’s murderous assault against the Syrian people, whether it be supervising massacres in rebel strongholds or launching chemical-weapon attacks against his own people.

Bashar’s ability, despite his glaring personal flaws, to survive this most brutal of conflicts is what persuaded me to write a book where I have sought to examine the complex and contradictory nature of the Syrian leader, and the key factors that have kept him in power.

For a man who was not born to be a dictator, Bashar al-Assad has done a pretty good job of brutalising his people. On his watch, an estimated 500,000 Syrians have lost their lives, while millions more have been forced to flee their homes. In March this year, 12 years after the start of the conflict, the UN estimated that 15.3 million Syrians were in need of humanitarian assistance.

It was not supposed to be like this. Bashar al-Assad was never intended to be the leader of Syria. The role of heir apparent had resided with his older brother, Bassel. He was a playboy, portrayed by the ruling Baath Party as the ‘Golden Knight’, who lived up to his image by becoming the darling of Beirut’s lively nightclub scene.

Hopes that Bassel would succeed his father, however, ended in January 1994, when he was involved in a fatal car crash while driving to Damascus airport shortly before his 32nd birthday.

At the time of his brother’s death, Bashar, then aged 28, was living a quiet and relatively obscure existence in London as a medical student. Diffident, speaking with a slight lisp, he lived in an apartment in a townhouse in Belgravia, with two Syrian security guards in constant attendance. He rarely socialised, and to relax listened to Phil Collins and Whitney Houston.

When he had first indicated his preference to complete his studies in London, having acquired a degree in medicine in Damascus, the British government was not overjoyed at the prospect of hosting a prominent member of the Assad clan in the capital.

Britain has a strained relationship with Damascus, dating back to a failed attempt by Syrian intelligence to blow up an Israeli passenger jet at Heathrow in 1986. Nevertheless, a family acquaintance who was on good terms with Downing Street offered to intervene on Bashar’s behalf, and he was offered a place to study ophthalmology at the Western Eye Hospital.

The young Assad took a keen interest in technology, especially computers. When he did venture out, he often used a pseudonym, especially when socialising among London’s vibrant Arab community. Despite his hard work, his supervisors did not think he was a particularly impressive student.

‘He was diligent – pleasant enough to work with – but pretty ordinary,’ recalled a former tutor who supervised his studies during the 18 months Bashar was in London. As the tutor recalls, ‘One day, a big black limousine appeared and whisked him away, never to be seen again.’

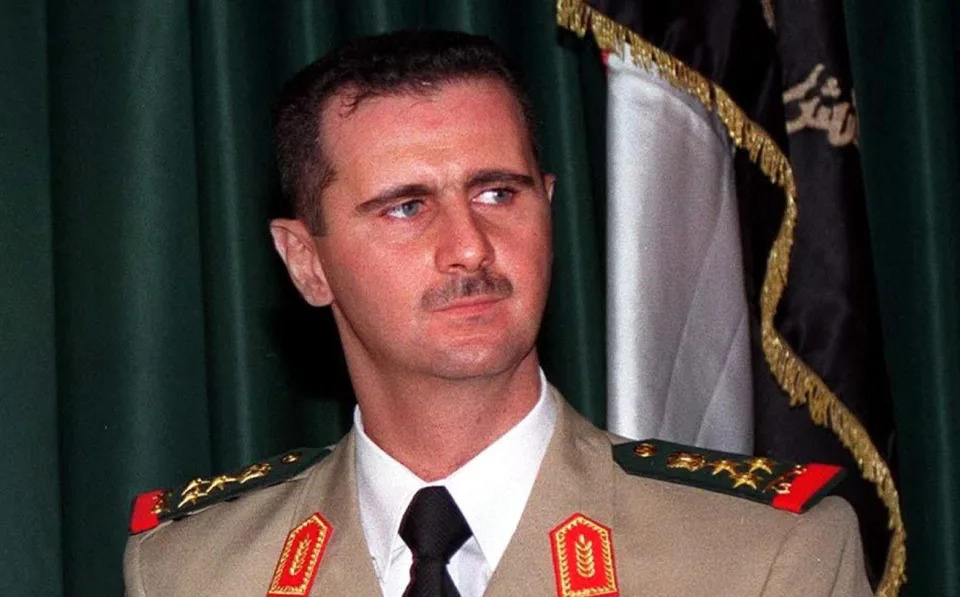

A private jet touched down in London, ready to return the second son to his homeland, where he succeeded Bassel as the president’s heir apparent. On his father’s orders, Bashar was given a crash course in the political and diplomatic skills necessary to control a fractious state like Syria – a position to which he was temperamentally unsuited. As his father remarked to a close acquaintance at the time, ‘Syria is a jungle, and Bashar is not yet a wolf.’

When he first assumed the presidency in the summer of 2000, Bashar was greeted as a refreshing change. Syria had endured decades of oppressive rule during the 30 years of his father’s dictatorship.

The image Bashar presented to the outside world during the early years was that of a well-educated and dynamic leader whose objective was to modernise the country by implementing radical political and economic reforms.

In his first address as President, he spoke passionately about making the economy and education the focus of his ambitious reform programme. ‘I find it very important to invite every citizen to participate in the journey of development and modernisation if we’re really sincere and serious about attaining desired results in the shortest possible time.’

During Hafez’s repressive rule, any hint of political opposition was instantly crushed, and the economy was controlled by a corrupt clique of Baathist loyalists. Bashar was keen to portray himself as the antithesis of his father.

Not only was he Western-educated, but he had also acquired a glamorous wife, 25-year-old Asma al-Akhras, the daughter of a London-based Syrian cardiologist, whom he had met during his studies

Asma – known to her British friends as Emma – had graduated from King’s College London with a degree in computer science. ‘She was very polite,’ recalls a childhood acquaintance who lived in the same street as the al-Akhras, in the unremarkable west London suburb of Acton.

Marriage to Asma certainly helped to make Assad more appealing to the outside world. When Tony Blair arranged for the couple to meet the Queen at Buckingham Palace in December 2002 as part of a diplomatic charm offensive to get Damascus to back the invasion of Iraq, glittering profiles of the Middle Eastern power couple appeared in the British press, with Asma dubbed an ‘icon’.

Yet behind the scenes, Assad was riven with self-doubt, and – perhaps because of this – already making his authoritarian nature known. ‘There was always this feeling with Bashar that he was trying to be two people at the same time,’ a close family friend told me. ‘One half of him was trying to be his father, the other half was trying to be Bassel.’

‘Bashar was always in his father’s shadow, and in his big brother’s shadow,’ recalled another contemporary. ‘He hated it when people underestimated him.’

And so, he cracked down on the nascent reform groups that had emerged after his father’s death, sidelined those deemed not sufficiently enthusiastic about his accession and promoted key allies to key positions in the Baathist regime. His younger brother, Maher, was given command of the Syrian military’s elite 4th Armoured Division.

Yet the world turned a blind eye. Even as the storm clouds of popular unrest began to gather in the first days of the Arab Spring in early 2011, US Vogue published a profile of Asma, entitled ‘A rose in the desert’.

In it the Assads were described as a ‘wildly democratic’, family-focused couple who took their vacations in Europe, fostered Christianity, were at ease with American celebrities and whose only ambition was to make their beloved country ‘the safest in the Middle East’.

The veneer of respectability the Assads had acquired through their carefully curated PR campaign evaporated the moment the regime found itself under threat as a result of the anti-government protests that erupted during the Arab Spring.

Political unrest had been simmering beneath the surface in Damascus ever since Assad had taken power and his promised political and economic reforms never happened.

Within days of the first Syrian protests in Deraa, in the south of the country, in March 2011, Bashar revealed a pathological ruthlessness. Under his command, a new security apparatus, the sinisterly named Central Crisis Management Cell (CCMC), was set up. Its main task was to identify the primary centres of the revolt, and target them with massacres of civilian protesters on an industrial scale.

In one notorious incident in the Tadamon suburb of Damascus in April 2013, Syrian forces dug a large trench in one of the main streets before executing more than 280 people, whose bodies were then dumped in the mass grave.

The CCMC also established a nationwide network of detention centres where suspected opponents of the regime were subjected, under direct orders from the President, to terrible abuse: held for prolonged periods during which they were subjected to intimidation, physical violence and torture. Sexual violence, including rape, was a regular occurrence, involving women, men and even children.

Over the course of the next two years, thousands of detainees died in custody in Damascus, and when a defector from the Syrian military smuggled pictures of the dead out of the country, their injuries were consistent with torture, starvation and suffocation. They were, he said later, ‘torturing to kill’.

So how did this mild-mannered ophthalmologist and his suburban British wife end up as some of the world’s most prolific killers?

Assad himself was not a natural war leader: racked by indecision, close aides complained that he could change his mind 20 times in a single day, making it impossible for commanders to issue clear instructions.

On the one hand he was promising reform while at the same time personally supervising brutal reprisals. This made it immensely difficult for officials to ascertain the President’s main objectives, which only added to the sense of confusion at the heart of the regime’s response.

Robert Ford, who served as US Ambassador to Damascus at the start of the conflict, was never in any doubt as to who was ultimately responsible for the Syrian’s regime’s brutality. ‘I never saw one iota of evidence that Bashar was trying to rein them [the hardliners] in,’ he recalled.

‘He was not in control of the day-to-day tactics: he just told his senior security officials to get on with it. He would say to his advisors: “You know what you have to do.” We never got any idea that he was urging restraint.’

Even so, Assad, and to a lesser degree Asma, seemed to be in a constant state of denial about their role in the violence. Later on in the conflict, when confronted with an Amnesty International report detailing the regime’s appalling abuses, Assad blithely dismissed the findings.

‘You can forge anything these days,’ he remarked in a rare interview with The Wall Street Journal. ‘We are living in a fake news era.’ He went on to claim that photographs of the corpses of prisoners piled up in a Damascus hospital had been put together by ‘photo-shop’.

In public, Assad tried to maintain a tough guy image, constantly railing against the enemies who were trying to overthrow his regime. But his lack of effective leadership qualities was laid bare after Iran became more involved in the conflict.

After Tehran agreed to respond to Assad’s plea for help following the influx of thousands of Islamist fighters to the rebel side from neighbouring Iraq, Qasem Soleimani, the leader of the Iranian Quds Force, effectively took personal control. ‘It had got to the point where Soleimani would go to see Assad to tell him what was going on as a matter of courtesy,’ explained a former senior US intelligence official.

Assad’s involvement in his own war was reduced further after Soleimani persuaded Vladimir Putin to join the fight. ‘From the moment they arrived, the Russians dictated their terms… Russian commanders had no interest in informing Assad what was going on,’ recalls a former Syrian officer.

Meanwhile, Asma’s efforts to distance herself from the regime’s atrocities were undermined somewhat after the Metropolitan Police announced in 2021 that it was conducting an investigation into her involvement in war crimes, a move that could ultimately result in her standing trial and losing her British citizenship.

But somehow, the Assads remain leaders of Syria and despite everything, the President and his wife are quietly enjoying a period of rehabilitation, at least in the Arab world.

With attention fixed on more pressing issues, such as the war in Ukraine, a number of Arab countries have begun re-establishing diplomatic ties with Damascus – so much so that Syria was last month invited to rejoin the Arab League, and more recently, the UAE issued an invitation to Assad to attend the Cop28 global summit later this year.

The many interviews with the survivors of the Syrian conflict that I conducted for my book led me to conclude that the only way that both Assad and Asma have been able to survive the horrors of the civil war was by living in a parallel universe – one where the narrative they had constructed for themselves set them as the innocent victims of a violent uprising that had forced them to defend their country and their people.

It remains to be seen whether the Assads will ultimately be able to escape justice for their participation in the violent suppression of the Syrian people. Lawyers and activists across the globe have already accumulated compelling evidence relating to numerous war crimes; now that the International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, many Syrians believe it is simply a question of time before the Assads suffer a similar fate.

Certainly, until the Assads are held fully accountable for their crimes, for the Syrian people it will simply be a case that justice delayed is justice denied.

Assad: The Triumph of Tyranny is published by Picador at £25. To order your copy for £19.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books

Read an exclusive extract from Assad: The Triumph of Tyranny

On 10 June 2000 Bashar al-Assad made his usual early morning call at the Presidential Palace to check on his father’s health. He knew that the ailing dictator was nearing the end of his life, but nonetheless it came as a shock when he entered the bedroom and found his father’s lifeless body lying peacefully in his bed. Hafez was just a few months short of his seventieth birthday. The rest of the house was still asleep and Bashar, who had anticipated this moment for several weeks, knew that he had to move quickly to secure the succession. He may have been his father’s choice to become the next president of the Syrian Arab Republic, but his appointment was by no means a foregone conclusion.

Bashar’s first instinct was to make sure that no one else in the family knew that Hafez had died during the night. Having respectfully tended to his dead father’s body, he left the room and quietly locked the door, putting the key in his pocket. He then went to a neighbouring room, where his mother Anisa was staying, and informed her that her husband was resting after a difficult night and was not to be disturbed. Reassuring her that he would come back later that morning to check on his father’s health, he hurried to his office in the presidential complex to begin implementing the carefully laid plan that would guarantee his succession.

One of his first calls was to Mustafa Tlass, the long-serving head of Syria’s armed forces and a veteran Baathist associate of his father. Tlass was one of a select group of trusted Baathists who had been given responsibility for implementing Hafez’s dying wish for Bashar to take control; he had no hesitation in implementing the well-rehearsed plan to ensure a peaceful transition of power. Within hours of hearing the news that Hafez was dead, Tlass had arranged for three army divisions to station tanks and armoured units at key points around Damascus. For good measure, Bashar’s younger brother Maher, a senior commander in the Republican Guard, deployed his elite forces too. It was only after these vital measures had been taken to safeguard the regime that Bashar returned to his father’s quarters to break the news to his mother and the rest of the family that Hafez had died in his sleep.

Having taken precautions to prevent any serious challenge to the status quo, Bashar spent the next few days attending to the other key issues that needed addressing before he could assume the presidency. The first obstacle was to make changes to the Syrian constitution, which stipulated that the minimum age for a president-elect was forty. Bashar was still only thirty-four. A meeting of the People’s Assembly, the regime’s rubber-stamp parliament, was hastily arranged and – perhaps unsurprisingly – voted unanimously to amend Article 83 of the constitution. Henceforward, the minimum age for Syria’s president-elect would be thirty-four.

Over the course of the next few days, Bashar’s nomination as secretary general of the Baath Party was approved, as was his promotion to the country’s highest military rank of fariq, or commander of the armed forces. Within days of his father’s demise, Bashar had successfully ensured that he would be Syria’s next dictator. The unbending confidence and efficiency that Bashar displayed as he moved to secure his dynastic inheritance so soon after losing his father took many by surprise, not least those who had questioned whether he had the charisma and strength of character required to lead a fractious and challenging country like Syria.

The self-assured demeanour that Bashar demonstrated in the days immediately following his father’s death was certainly unexpected by those who did not know him well. Gone was the diffident medical student; instead, foreign dignitaries paying their respects to the Assad family were surprised at Bashar’s composure. One of the first visitors to the Presidential Palace, a close family friend, recalled how relaxed the heir apparent had seemed. Far from being overwhelmed by the loss of the man who had dominated Syria for nearly three decades, Bashar was at pains to reassure his guest that he had everything under control. When the friend asked the young president in-waiting to ‘assure me that you have done everything that needs to be done to make sure the regime transition takes place’, he was taken aback at the boldness of the response. ‘You see these hands,’ Bashar replied, raising both his palms. ‘When people look at my hands, they think they are soft, as though I am wearing velvet gloves. But they are very mistaken. For, if I take them off, you will see an iron fist.’