مايكل يونغ/ذا ناشيونال: للرئيس اللبناني نفوذ لكن تحالفه مع حزب الله لم ينته بعد

Lebanon’s president has leverage but his alliance with Hezbollah isn’t over

Michael Young/The National/January 05/2022

Hezbollah’s critics should support Michel Aoun’s calls to talk about a national defence strategy.

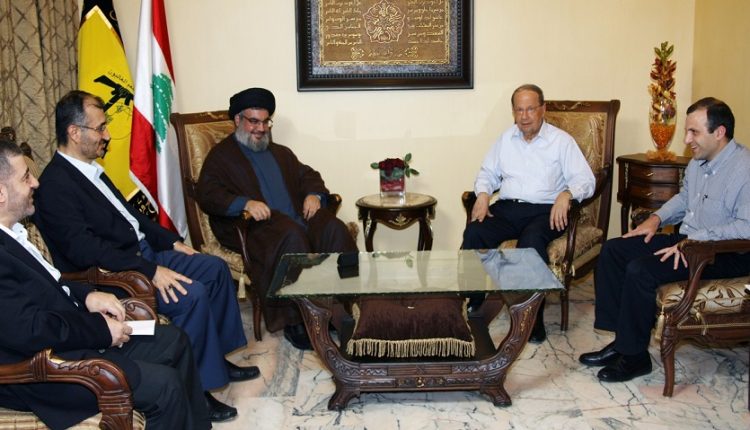

In a speech two days after Christmas, Lebanese President Michel Aoun took a novel position on Hezbollah that contrasted sharply with his enduring appeasement of the party. While the speech received mixed reviews, Mr Aoun did create an opening that Hezbollah’s critics must exploit to try to find a solution for its weapons.

In his speech, the president called for an urgent national dialogue around a national defence strategy for Lebanon, along with other objectives. Agreement over a defence strategy has particular resonance for Hezbollah, as this is another term for finding a formula to integrate the party’s weapons arsenal into the state. Mr Aoun declared: “It’s true that defence of the country requires co-operation among the army, the people, and [Hezbollah], but the prime responsibility belongs to the state. Only the state can establish a defence strategy and supervise its implementation.”

In a broadside aimed at Hezbollah and the allied Amal movement, Mr Aoun continued: “Before reaching this stage, we need to begin by putting an end to the deliberate, systematic, and unjustified blockage leading to the dismantling of institutions and the dissolution of the state.” Both Hezbollah and Amal are boycotting cabinet sessions until a resolution is found for the investigation of the Beirut port explosion. Hezbollah wants the investigating magistrate, Tarek Bitar, removed from the case, because he is trying to interrogate former ministers affiliated with the party’s allies.

Mr Aoun’s rivals dismissed his comments as too little, too late. They noted that the president’s purpose in highlighting his differences with Hezbollah was to push the party to support the presidential ambitions of his son-in-law, Gebran Bassil. Unless it did so, Mr Aoun implied, his alliance with Hezbollah was open to reconsideration.

There is considerable truth to that conclusion. However, disregarding the president’s remarks and leaving things at that would be a mistake. After 2005, when Syria’s army was forced to withdraw from Lebanon, those seeking Hezbollah’s negotiated disarmament were frustrated because the party had allied itself with Mr Aoun’s and Mr Bassil’s Free Patriotic Movement. This created a political stalemate in Lebanon that prevented progress in pushing the party to surrender its weapons.

It would be premature today to assume that the Aoun-Hezbollah alliance is over. If anything, Mr Aoun is opportunistically holding up the possibility of a divorce to avoid such an outcome by ensuring that Mr Bassil can succeed him.

However, for the first time the president has placed the formula for a defence strategy on the table – based on a Hezbollah that must be subordinate to the state, and therefore whose weapons, implicitly, must be integrated into a larger entity that retains paramount responsibility for defending the nation. The party, which is keen on preserving an independent military capability outside the confines of the state, mainly to benefit Iran, is unwilling to enter into a serious national discussion on the matter.

If Hezbollah were to commit to Mr Bassil’s presidency now, Aoun might move away from his call for a dialogue on a defence strategy.

Yet Mr Aoun has some leverage, as Hezbollah regards his endorsement of its status as a resistance force as valuable official legitimisation. Were Mr Aoun to withdraw this, the party would be isolated against a majority of Lebanese who believe the main problem in their country is the presence of an armed group acting as a proxy for a foreign power and that will always impose a debilitating status quo to protect its interests.

If Hezbollah’s critics should do anything, it is to collectively support Mr Aoun’s calls for a dialogue over a national defence strategy, and insist it begin as soon as possible. Hezbollah made it clear after the president’s speech that now was not the time to discuss this. That is precisely why Hezbollah’s rivals should try to take advantage of the space between the president and the party to work toward that objective.

If Hezbollah were to commit to Mr Bassil’s presidency now, it is likely that the president would move away from his call for a dialogue on a defence strategy. However, it is highly improbable that it will do so. Hezbollah prefers to leave its options open and may be under pressure from Syria to back a more overtly pro-Syrian president.

In that case, Mr Aoun may be thinking of something else. He realises that a majority of his Christian co-religionists do not sympathise with Hezbollah’s state within a state. Amid Lebanon’s severe economic crisis, the party has alienated many Arab countries, leaving the Lebanese isolated and facing poverty, with little outside help. Nor does the prospect of a war with Israel on Iran’s behalf appeal to Christians, or anyone. Christians also are especially keen to see Mr Bitar pursue his investigation.

If Mr Aoun can make progress over a defence strategy, he feels he might bolster his Christian bona fides and help his party in elections in May – and perhaps even Mr Bassil’s chances. The party will not give up its weapons, but if its rivals, along with Mr Aoun, can limit its margin of manoeuvre somewhat, this could be something to build upon in the future. Mr Aoun may feel this is a fight worth embarking on, whether it succeeds or not, because his party and Mr Bassil desperately need to revive their political appeal.

***Michael Young is a Lebanon columnist for The National