ريموند إبراهيم: الإبادة الأرمنية ماضياً وحاضراً ومستقبلاً

The Armenian Genocide: Past, Present, and Future?

Raymond Ibrahim/September 08/2021

On April 24, 2021, Joe Biden became the first sitting U.S. president formally to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide. What was this genocide about, and what is its significance for today?

The Genocide Education Project offers a summary of that tragic event which transpired during World War I, specifically between 1915 and 1917:

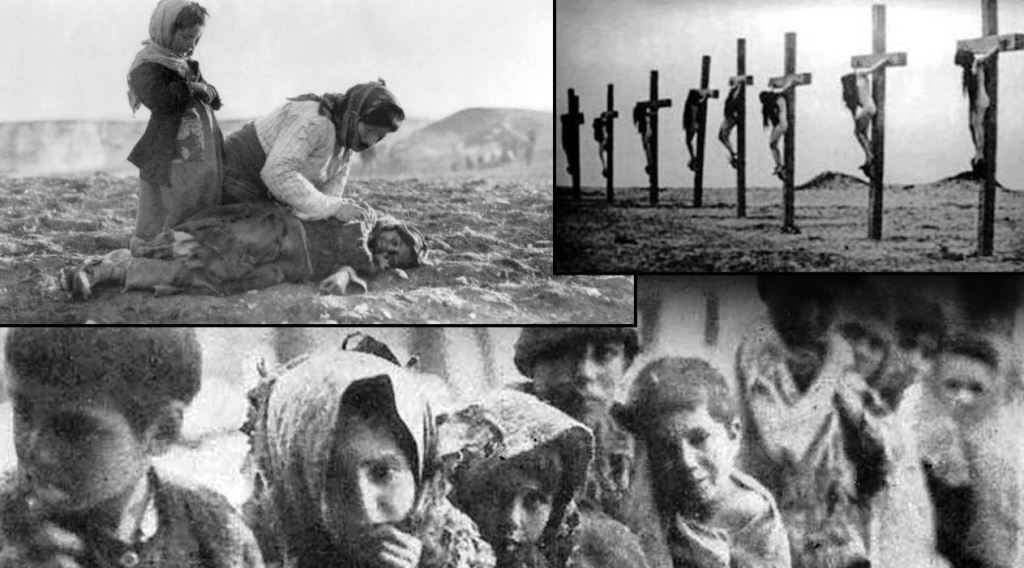

More than one million Armenians perished as the result of execution, starvation, disease, the harsh environment, and physical abuse. A people who lived in eastern Turkey for nearly 3,000 years [more than double the amount of time the invading Islamic Turks had occupied Anatolia, now known as “Turkey”] lost its homeland and was profoundly decimated in the first large-scale genocide of the twentieth century. At the beginning of 1915 there were some two million Armenians within Turkey; today there are fewer than 60,000…. Despite the vast amount of evidence that points to the historical reality of the Armenian Genocide, eyewitness accounts, official archives, photographic evidence, the reports of diplomats, and the testimony of survivors, denial of the Armenian Genocide by successive regimes in Turkey has gone on from 1915 to the present.

The evidence is indeed overwhelming. As far back as 1920, U.S. Senate Resolution 359 heard eyewitness testimony concerning the “[m]utilation, violation, torture, and death [which] have left their haunting memories in a hundred beautiful Armenian valleys, and the traveler in that region is seldom free from the evidence of this most colossal crime of all the ages.”

In her memoir, Ravished Armenia, Aurora Mardiganian described how she was raped and thrown into a harem (consistent with Islam’s rules of war). Unlike thousands of other Armenian girls who were discarded after being defiled, she managed to escape. In the city of Malatia, she saw 16 Christian girls crucified: “Each girl had been nailed alive upon her cross,” she wrote, “spikes through her feet and hands, only their hair blown by the wind, covered their bodies.” (Such scenes were portrayed in the 1919 documentary film Auction of Souls, some of which is based on Mardiganian’s memoirs.)

In short, that the Turks orchestrated and carried out a deliberate genocide of Armenians during World War I is an uncontested fact—for those who still care about facts—irrespective of who does or does not acknowledge it (Turkey itself epitomizing the latter category).

Even so, the extent of Turkish atrocities committed against Armenians far exceeds the Armenian Genocide. In fact, it is more appropriate to see the latter, not as a singular event, but as an especially severe segment of an ancient and ongoing continuum.

The Genocide before the Genocide

The Turks’ initial genocide of Armenians began slightly over a thousand years ago, when the Muslim tribesmen first began to pour into and transform a then much-larger Armenia into what it is today: the eastern portion of modern-day Turkey.

Thus, in 1019, “the first appearance of the bloodthirsty beasts … the savage nation of Turks entered Armenia … and mercilessly slaughtered the Christian faithful with the sword,” writes Matthew of Edessa (d.1144), a chief chronicler for this period. Three decades later, the raids were virtually nonstop. In 1049, the founder of the Seljuk Empire himself, Sultan Tughril Bey (r. 1037–1063), reached the unwalled city of Arzden, west of Lake Van, and “put the whole town to the sword, causing severe slaughter, as many as one hundred and fifty thousand persons.”

After thoroughly plundering the city, he ordered it, including 800 churches, to be set ablaze and turned into a desert. Arzden was “filled with bodies” and none “could count the number of those who perished in the flames.” Eight hundred oxen and forty camels were required to cart out the vast plunder, mostly taken from Arzden’s churches. “How to relate here, with a voice stifled by tears,” continues Matthew, the many butchered Armenians who were “left without graves” and “became the prey of carrion beasts,” and “the exodus of women … led with their children into slavery and condemned to an eternal servitude! That was the beginning of the misfortunes of Armenia,” laments the chronicler, “so, lend an ear to this melancholy recital.”

Other contemporaries confirm the devastation visited upon Arzden. “Like famished dogs,” writes Aristakes (d.1080) an eyewitness, the Turks “hurled themselves on our city, surrounded it and pushed inside, massacring the men and mowing everything down like reapers in the fields, making the city a desert. Without mercy, they incinerated those who had hidden themselves in houses and churches.”

Eleven years later, during the Turkish siege of Sebastia (modern-day Sivas) in 1060, 600 churches were destroyed and “many [more] maidens, brides, and ladies were led into captivity.” Another raid on Armenian territory saw “many and innumerable people who were burned [to death].” The atrocities are too many for Matthew to recount, and he frequently resigns in lamentation:

Who is able to relate the happenings and ruinous events which befell the Armenians, for everything was covered with blood. . . . Because of the great number of corpses, the land stank, and all of Persia was filled with innumerable captives; thus this whole nation of beasts became drunk with blood.

Then, between 1064 and 1065, Tughril’s successor, Sultan Muhammad bin Dawud Chaghri—known to posterity as Alp Arslan, one of modern Turkey’s most celebrated heroes—laid siege to Ani, the fortified capital of Armenia, then a great and populous city. The thunderous bombardment of Muhammad’s siege engines caused the entire city to quake, and countless terror-stricken families are described in memoirs as huddling together and weeping.

Once inside, the Turks—reportedly armed with two knives in each hand and an extra in their mouths—“began to mercilessly slaughter the inhabitants of the entire city … and piling up their bodies one on top of the other…. Innumerable and countless boys with bright faces and pretty girls were carried off together with their mothers.”

Not only do several Christian sources document the sack of Armenia’s capital—one contemporary succinctly notes that Muhammad “rendered Ani a desert by massacres and fire”—but so do Muslim sources, often in apocalyptic terms: “I wanted to enter the city and see it with my own eyes,” one Arab explained. “I tried to find a street without having to walk over the corpses. But that was impossible.”

Such is an idea of how Armenian/Turkish relations began—nearly a millennium before the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1917. The Turks naturally put the Armenians through much more in the intervening centuries—Sultan Abdulhamid massacred as many as 300,000 Armenians in the name of Islam between 1894-1896—but this should suffice as a glimpse of the past.

A Holy Hate

While human conquests are as old as time, why was the initial Turkish conquest of Armenia so inundated with excessive acts of cruelty? The answer is that, for the Turks and other Muslim peoples, conquering “the other” was further imbued with a pious rationale—an ideology, the necessary ingredient for sadistic hatred and its natural culmination: genocide. What Jews and Christians were taught was “sin”—murder and rape—took on a noble and sacred character for the already rapacious Turks, so long as their victims were non-Muslims, which by default made them enemies—“infidels” whom Islamic law requires to be killed, subjugated, or enslaved.

As Gregory Palamas, a clergyman who was taken captive by the Turks wrote in 1354, “They live by the bow, the sword, and debauchery, finding pleasure in taking slaves, devoting themselves to murder, pillage, spoil … and not only do they commit these crimes, but even—what an aberration—they believe that God approves them!” Nor were the Armenians unaware of what fueled Turkish animus: “[They attack] us because of our Christian faith and they are intent … on exterminating the Christian faithful,” one David, an Armenian chieftain, explained to his countrymen during the Muslims’ eleventh century invasions.

Equally telling is that the most savage treatment was always reserved for those visibly proclaiming their Christianity. During the aforementioned sack of Arzden, the Muslim invaders “burned priests whom they seized in the churches and massacred those whom they found outside. They put great chunks of pork in the hands of the undead to insult us”—Muslims deem the pig unclean—“and made them objects of mockery to all who saw them.”

Similarly, during the sack of Ani, clergy and monks “were burned to death, while others were flayed alive from head to toe,” writes Matthew. Every monastery and church—before this, Ani was known as “the City of 1001 Churches”—was desecrated and set aflame. A zealous jihadi climbed atop the city’s main cathedral “and pulled down the very heavy cross which was on the dome, throwing it to the ground.” Made of pure silver and the “size of a man”—and now symbolic of Islam’s might over Christianity—the broken crucifix was sent as a trophy to adorn a mosque in modern-day Azerbaijan.

The Armenian Genocide and Religion

Did this same early Muslim animus for “infidels” also fuel the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1917? Unfortunately, since its occurrence, the West has usually articulated the genocide through a singularly secular paradigm, one that only factors things such as territorial disputes and nationalism. While there is some merit to this approach, so too does it invariably project modern Western motivations onto vastly different peoples and projects.

In fact, it was the Armenians’ religious identity that ultimately led to the Armenian Genocide. This is underscored by the often-overlooked fact that, along with killing 1.5 million Armenians, the Turks also systematically massacred approximately 750,000 Greeks and 300,000 Assyrians—Christians all—during World War I. As one Armenian studies professor rhetorically asked, “If it [the Armenian Genocide] was a feud between Turks and Armenians, what explains the genocide carried out by Turkey against the Christian Assyrians at the same time?” From a Turkish perspective, the primary thing Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks had in common was that they were all Christian “infidels,” and therefore existential enemies.

As such, the genocide can be seen as the culmination of the Ottoman Empire’s jihad on its Christian population. According to the 2017 book, Year of the Sword: The Assyrian Christian Genocide, the “policy of ethnic cleansing was stirred up by pan-Islamism and religious fanaticism. Christians were considered infidels (kafir). The call to Jihad, decreed on November 29, 1914 and orchestrated for political ends, was part of the plan… [to] combine and sweep over the lands of Christians and to exterminate them.” As with Armenians and Greeks, eyewitness accounts tell of the eye-gouging of Assyrians and the gang rape of their children on church altars—hallmarks of jihadist sadism. According to key documents, all this was part of “an Ottoman plan to exterminate Turkey’s Christians.”

As for the argument that, because all of these genocidal atrocities occurred during World War I, they are, ultimately, a reflection of just that—war, in all its death-dealing destruction—reality is different. War was a factor, but only because it offered the Turks the cover to do what they had long wanted to do anyway. After describing the massacres as an “administrative holocaust,” Winston Churchill correctly observed that “The opportunity [WWI] presented itself for clearing Turkish soil of a Christian race.” Or, in the clear words of Talaat Pasha, the de facto leader of the Ottoman Empire during the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1917: “Turkey is taking advantage of the war in order to thoroughly liquidate its internal foes, i.e., the indigenous Christians, without being thereby disturbed by foreign intervention…. The question is settled. There are no more Armenians.”

The Nagorno-Karabakh War

Sadly, recent events indicate that, far from being repentant for the Armenian Genocide, the Turks still regard the Armenians with genocidal intent.

In October 2020, war erupted between Armenia and its other Muslim neighbor, Azerbaijan, over the disputed territory now known as Nagorno-Karabakh. Although it was Armenian for thousands of years, known as Artsakh, and remains predominantly Armenian, after the dissolution of the USSR, it was allotted to Azerbaijan, causing problems since and culminating in the recent war. (See “15 Artsakh War Myths Perpetuated By Mainstream Media.”)

Turkey quickly joined its Azerbaijani co-religionists and arguably even spearheaded the war against Armenia, though the dispute clearly did not concern it. As Nikol Pashinyan, Armenia’s prime minister, rhetorically asked on October 1, 2020, “Why has Turkey returned to the South Caucasus 100 years [after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire]?” His answer: “To continue the Armenian Genocide.”

Among other things, Turkey funded Sharia-enforcing “jihadist groups,” to quote French President Macron, that had been operating in Syria and Libya—including the pro-Muslim Brotherhood Hamza Division, which kept naked, sex slave women in prison—to terrorize and slaughter the Armenians.

One of these captured mercenaries confessed that he was “promised a monthly $2,000 payment for fighting against ‘kafirs’ in Artsakh, and an extra 100 dollar[s] for each beheaded kafir.” (Kafir, often translated as “infidel,” is Arabic for any non-Muslim who fails to submit to Islam, which makes them enemies by default.)

Among other ISIS-like behavior committed by this Islamic coalition of mercenaries, Turks, and Azerbaijanis, they “tortured beyond recognition” an intellectually disabled 58-year-old Armenian woman by sadistically hacking off her ears, hands, and feet, before finally executing her. Her family were only able to identify her by her clothes. Similarly, video footage shows camouflaged soldiers overpowering and forcing down an elderly Armenian man, who cries and implores them for mercy, before they casually carve at his throat with a knife. In one instance—and as has happened countless times throughout the ages—a jihadist stood atop an Armenian church, after its cross had been broken off, and triumphantly cried “Allahu Akbar!”

Incidentally, and as might be expected, Azerbaijan shares in Turkey’s Islamic hostility for Armenians. According to a March 27, 2021 report, over the course of just two weeks, at least three Armenian churches in the Nagorno-Karabakh region were vandalized or destroyed—even though a ceasefire was declared in November. Video footage shows Azerbaijani troops entering into one of the churches, laughing, mocking, kicking, and defacing Christian items inside it, including a fresco of the Last Supper. Turkey’s flag appears on the Azeri servicemen’s uniform, further implicating that nation. As they approach, one of the soldiers says, “Let’s now enter their church, where I will perform namaz.” Namaz is a reference to Muslim prayers; when Muslims pray inside non-Muslim temples, those temples immediately become mosques. In response to this video, Arman Tatoyan, an Armenian human rights activist, issued a statement:

The President of Azerbaijan and the country’s authorities have been implementing a policy of hatred, enmity, ethnic cleansing and genocide against Armenia, citizens of Armenia and the Armenian people for years. The Turkish authorities have done the same or have openly encouraged the same policy.

By way of example, he said that Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev proudly stated in early March that “the younger generation has grown up with hatred toward the enemy,” meaning Armenians.

An Innate Hate?

The aforementioned hate, which is always a precursor to genocide, is evident everywhere in modern-day Turkey. One need only listen to the religiously-laden rant of a Turkish man about how all Armenians are “dogs” and that any found in Turkey should be slaughtered for an idea:

What is an Armenian doing in my country? Either the state expels them or we kill them. Why do we let them live?… We will slaughter them when the time comes…. This is Turkish soil. How are we Ottoman grandchildren?…. The people of Turkey who have honor, dignity, and Allah must cut the heads of the Armenians in Turkey. It is dishonorable for anyone to meet and not kill an Armenian… If we are human, let us do this—let us do it for Allah…. Everyone listening, if you love Allah, please spread this video of me to everyone…

Similarly, in response to a question being asked to random passersby on the streets of Turkey—“If you could get away with one thing, what would you do?”—a woman said on video: “What would I do? Behead 20 Armenians.” She then looked directly at the camera, and smiled while nodding her head.

Some might argue that the two above examples are circumstantial—that is, they reflect Turkish anger brought on by the Armenian/Azerbaijan conflict. But if that were the case, what does one make of the fact that Turkish hate and violence for Armenians goes back years before the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict?

Consider a few examples—all of which occurred before and therefore have no connection to the recent conflict—in no special order:

In 2013, an 85-year-old Armenian woman was stabbed to death in her Istanbul apartment. Lest anyone mistake the motive, her Turkish murderer carved a crucifix on her naked corpse. According to the report, that “attack marks the fifth in the past two months against elderly Armenian women (one has lost an eye).” In one instance, another octogenarian Armenian woman was punched in the head and, after collapsing to the floor, repeatedly kicked by a masked man.

On Sunday, February 23, 2019, threatening graffiti messages were found on the main entrance door of the Armenian Church of the Holy Mother of God in Istanbul. The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople said in a statement that “There were written racist and hate speeches in both English and Arabic [saying] you are finished!” An Armenian Member of Parliament tweeted, “Every year, scores of hate attacks are being carried out against churches and synagogues. Not just the perpetrators, but also the people who are behind them, should be addressed. For the most important part, the politics that produce hate should be ended.”

In August 2020, an Armenian cemetery and church were desecrated. According to the report, “the remains were taken out of the graves and the bones of the deceased were scattered everywhere” (pictures here).

On May 22, 2020 in broad daylight, a man climbed the fence of a historic Armenian church in Istanbul and proceeded to yank off its metal cross and hurl it to the ground, as captured on surveillance footage. Two weeks earlier, another Turk broke into Holy Cross, a historic Armenian cathedral in eastern Turkey, and proceeded to recite the adhan—the Islamic call to prayer traditionally made from mosques—punctuated by chants of “Allahu Akbar.”

At this point, it increasingly seems that, when it comes to Turkey’s genocidal hate for Armenians, not only is religion a factor; it is the deciding factor. This is evident in that, just as the Turks committed a genocide against other Christians than the Armenians—notably Greeks and Assyrians—so too is contemporary Turkish hostility directed against all Christians, not just Armenians. Consider the following examples, which have nothing to do with Armenians, and which occurred before the Nagorno-Karabakh.

In 2009, a group of young Turks—including the son of a mayor—broke into a Bible publishing house in Malatya. They bound, sadistically tortured for hours, and eventually slaughtered its three Christian employees, one of whom was German. “We didn’t do this for ourselves, but for our religion,” one of the accused later said. “Let this be a lesson to enemies of our religion.” They were all later released from prison on a technicality.

In late 2019, a Muslim boy, aged 16, stabbed a Korean Christian evangelist in the heart several times; the 41-year-old husband and father died shortly thereafter. Months earlier, an “86-year-old Greek man was found murdered in his home with his hands and feet tied”; he was reportedly “tortured.”

In 2019, two Muslim men beat a Christian teenager in the street after they noticed he was wearing a crucifix around his neck. The Protestant Association of Churches said in response that “This attack is a result of the growing hatred against Christians in Turkey. We invite government officials to take action against hate speech.”

Much more common than the targeted beating or killing of Christians—but no less representative of the hate—are church-related attacks. Thus, when a man opened fire on the Saint Maria Catholic Church in Trabzon in 2018, it was just the latest in several attacks on that church. Weeks earlier, a makeshift bomb was thrown at its garden; in 2016 Muslims crying “Allahu Akbar” vandalized the church, including with sledgehammers; in 2011 the church was targeted and threatened for its visible cross; and in 2006 its Catholic priest, Andrea Santoro, was shot dead while praying during church service.

Also while shouting “Allahu Akbar” and “Revenge will be taken for Al-Aqsa Mosque,” another Muslim man in 2015 hurled a Molotov cocktail at Istanbul’s Aya Triada Orthodox Church, partially setting it on fire. In another incident, in 2016, four Turks banged and kicked at the door of Agape Church in the Black Sea region—again while shouting “Allahu Akbar!,” thereby establishing their jihadist motives.

In 2014, a random gang of Muslims disrupted a baptismal church service in Istanbul. They pushed their way into the church, yelling obscenities; one menacingly waved a knife at those in attendance. “It’s not the first, and it won’t be the last,” a local Christian responded.

In late 2019, while shouting abusively and making physical threats against Christians gathered at the Church of St. Paul in Antalya, a man said he “would take great pleasure in destroying the Christians, as he viewed them as a type of parasitism on Turkey.”

One of the most alarming instances occurred in 2015: as many as 15 churches received death threats for “denying Allah.” “Perverted infidels,” one missive read, “the time that we will strike your necks is soon. May Allah receive the glory and the praise.” “Threats are not anything new for the Protestant community who live in this country and want to raise their children here,” church leaders commented.

In March, 2020, some 20 gravestones in just one Christian cemetery in Ankara were found destroyed. Separately, but around the same time, desecraters broke a cross off a recently deceased Catholic women’s grave; days earlier, her church burial service was interrupted by cries of “Allahu Akbar!”

In discussing all these attacks on anything and everything Christian—people, buildings, and even graves—Seyfi Genç, a journalist in Turkey, laid the blame on an “environment of hate”:

But this hateful environment did not emerge out of nowhere. The seeds of this hatred are spread, beginning at primary schools, through books printed by the Ministry of National Education portraying Christians as enemies and traitors. The indoctrination continues through newspapers and television channels in line with state policies. And of course, the sermons at mosques and talk at coffee houses further stir up this hatred.

All of this is a reminder that the primary ingredient—religiously-inspired hate—that led to the genocide of Christians (Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians) between 1915-1917, is not only alive and well, but growing—and no doubt waiting to be realized once the next opportunity presents itself.

In his April 24 statement on Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, 2021, President Biden said, “Each year on this day, we remember the lives of all those who died in the Ottoman-era Armenian genocide and recommit ourselves to preventing such an atrocity from ever again occurring [emphasis added].”

While this sounds promising, until such time that the root cause of the Armenian Genocide—the root cause for the ongoing persecution of hundreds of millions of Christians today—is recognized and dealt with, all such claims of vigilance must be relegated to the realm of theater.