Sixteen English Editorials, Analysis & Reports Addressing Recent Unfolding Important Events In Iranian Occupied Lebanon/

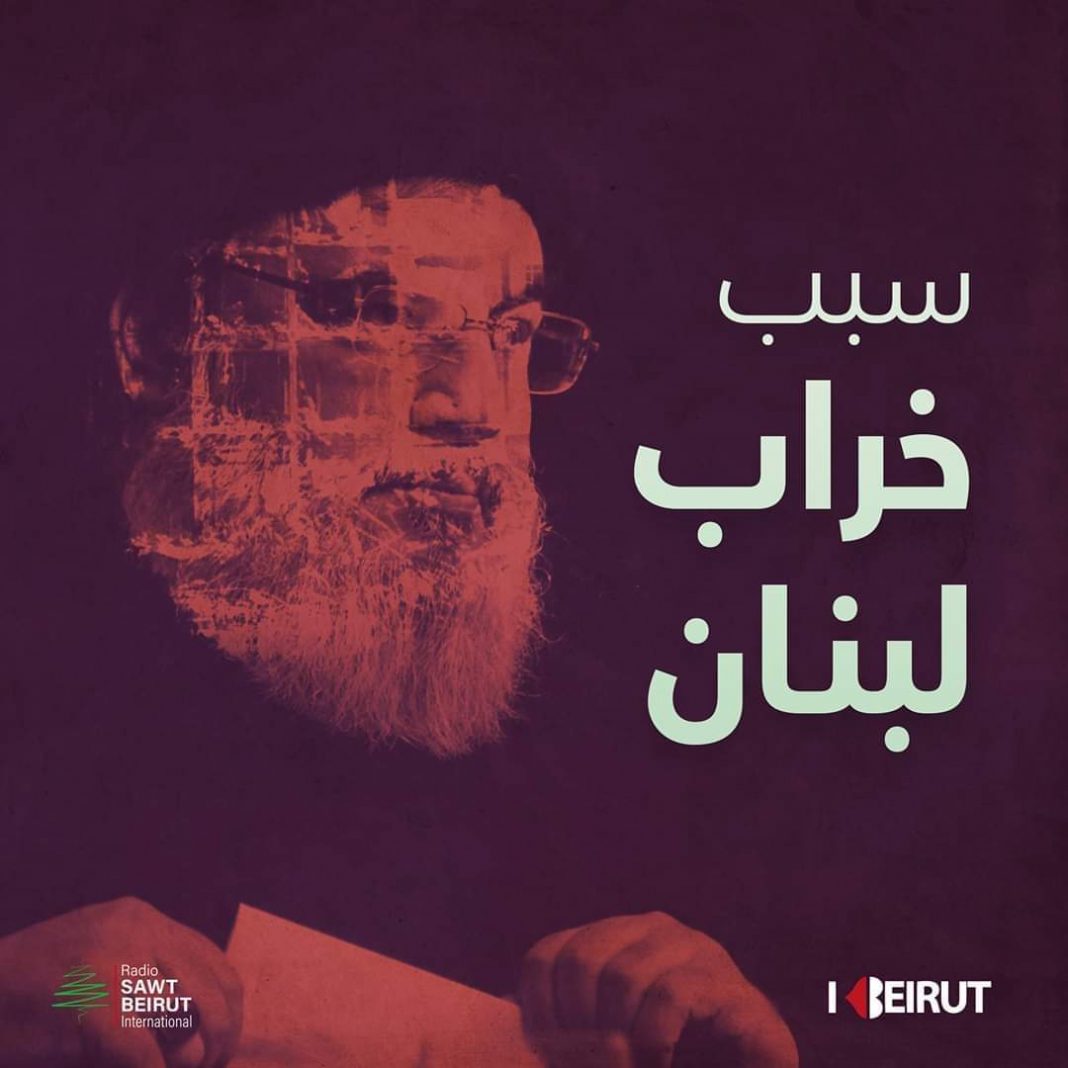

ستة عشر مقالة وتحليل وتقرير باللغة الإنكليزية يتناولون أخر التطوارات في لبنان الذي تحتله إيران وحزبها الإرهابي

*IDF attacks Hezbollah targets following incident on northern border/Arutz Sheva/August 26/2020

*A More Forceful France?/Ghida Tayar/Carnegie MEC/August 25/2020

*Hariri Says Doesn’t Want to Return as Premier/Naharnet/August 25/2020

*Riad Salameh: In Lebanon, depositors’ money is still available/Randa Takieddine/Arab News/August 25/2020

*Lebanon’s new start needs to be locally led/Javier Solana/Arab News/August 25/2020

*In fifteen years between Hariri’s assassination and the Beirut explosion what did we learn?/Dr Amira Abo el-Fetouh/Middle East Monitor/August 25, 2020

*Making Sense Of The Next Round Of Turmoil In Iraq And Lebanon/Alberto M. Fernandez/MEMRI Daily Brief /August 25/2020

*The American Mideast Coalition for Democracy (AMCD) Praises Trump Administration’s Historic Peace Deal between Israel and the UAE

*Weeks after blast, Lebanon patronage system immune to reform/Samya Kullab/AP/August 25/2020

*It’s time for Europe to follow Germany’s lead and ban Hezbollah/Jerusalem Post Editorial/August 25/2020

*City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut/Robyn Creswell/Reviewed by Franck Salameh/Middle East Quarterly/Summer 2020

*Syrians Lose Children, Homes and Jobs in Beirut Blast/Agence France Presse/Naharnet/August 25/2020

*After Beirut Blast, Foreign Workers Beg to Go Home/Agence France Presse/Naharnet/August 24/2020

*Occupation… Electronic Justice and the Mirage of an International Community

Sam Menassa/Asharq Al-Awsat newspaper/August, 24/2020

*Lebanese businesses rebel against lockdown

Najia Housari/Arab News/August 24/2020

*US Seeking to Reduce Number of UNIFIL Troops, Stop Hezbollah Violations

New York- Ali Barda/Asharq Al Awsat/August 24/2020

*******

IDF attacks Hezbollah targets following incident on northern border

Arutz Sheva/August 26/2020

IDF aircraft attack Hezbollah targets following incident on the northern border in which IDF forces were fired upon.

IDF combat helicopters and aircraft attacked Hezbollah terrorist targets early Wednesday morning following Tuesday’s incident on the northern border. The attack targeted observation posts of the terrorist organization located near the border with Lebanon. “The IDF considers the Lebanese government responsible for what happens in its territory. The IDF views the incident very seriously. Any attempt to violate the sovereignty of the State of Israel is a serious incident. The IDF will continue to maintain a high level of readiness in order to protect Israeli sovereignty and security,” the IDF Spokesperson’s Unit said in a statement.

Tuesday night’s security incident occurred around 10:40 p.m. near Kibbutz Menara when fire was opened toward IDF forces who were operating in the area. There were no injuries among the Israeli forces.

The troops responded by firing dozens of flash bombs and smoke shells.

Following the security incident in the north, the residents of Yiftach, Menara, Margaliot, Misgav Am and Malkia have been ordered to stay in their homes. Those restrictions were lifted early Wednesday morning.

The IDF Spokesperson’s Unit said that the residents “are prohibited from any activity in an open space, including agricultural work. Residents are required to stay in their homes and upon receiving a warning, to immediately enter a protected area – security/emergency room, shared shelter, internal stairwell or internal room in the house, close doors and windows and stay there for 10 minutes.”

“Please keep up to date with the guidelines disseminated in the media and obey the instructions of the security forces and the IDF operating in the area,” the statement added. According to one report, gunfire that was heard from the Lebanese side of the border alerted IDF forces who fired dozens of flares and conducted searches in the area. Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu was staying with his family on vacation at a hotel in Tzfat on Tuesday night. His office announced that he was holding security discussions following the incident and receiving regular updates about it. Defense Minister Benny Gantz also held consultations with Chief of Staff Aviv Kochavi following the incident.

About a month ago, an attempt was made to infiltrate Israeli territory near Har Dov in the vicinity of the Hermon. An IDF force identified the infiltration and opened fire.

The incident ended without any injuries, and the intruders fled into Lebanese territory. Israel filed a formal complaint with the UN Security Council following the incident.

A More Forceful France?

Ghida Tayar/Carnegie MEC/August 25/2020

https://youtu.be/65dq2vwwMYE

In an interview, Joseph Bahout discusses French policy toward the Levant and Mediterranean, and what we should watch for. Joseph Bahout is a nonresident scholar in Carnegie’s Middle East Program. He is also the incoming director of the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut (AUB), where he is also an associate professor of political science. Until 2019, Bahout taught Middle Eastern politics at Sciences-Po in Paris, where he was an associate professor. He worked as a permanent consultant for the policy panning unit of the French Foreign Ministry from 2008 until 2014, and again from 2018 until 2020. There, he was in charge of the Levant as well as U.S. policy toward the Middle East. Bahout was also a consultant on the Middle East in the presidential campaign of Emmanuel Macron. Diwan interviewed Bahout in late August to discuss French policy toward the Levant and the Mediterranean, particularly following Macron’s visit to Lebanon in the aftermath of the devastating explosion in Beirut Port on August 4.

Hariri Says Doesn’t Want to Return as Premier/Naharnet/August 25/2020

Ex-PM Saad Hariri declared Tuesday that he is not a candidate for the PM post and called on all political forces to withdraw his name from any deliberations in this regard. Hariri issued his statement following separate talks with Qatari Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdul Rahman al-Thani and Lebanese General Security chief Maj. Gen. Abbas Ibrahim. Below is the full text of an English-language statement distributed by Hariri’s press office: “I had committed not to take a political position before the pronouncement of the judgment of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon on the assassination of the martyr Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, and before having completed contacts with friendly countries, the international community and Lebanese political forces regarding the initiative that President Emmanuel Macron presented during his recent visit to Lebanon. In reality, I consider that the renewed international interest in our country, and especially the initiative of President Macron and the visits of a certain number of international and Arab officials, represent an opportunity which could be the last and cannot be failed, to rebuild our beloved capital Beirut, and to achieve a series of reforms that the Lebanese have demanded and that we have been trying to implement for many years. This is an opportunity to break the economic and financial isolation that Lebanon suffers from, with external resources that would first allow to stop the frightening collapse and then gradually shift to resuming growth.

With my sincere thanks to all those who proposed my name as a candidate to form a government that would undertake this national task, that is noble and difficult at the same time, I noticed, like all other Lebanese, that certain political forces are still in a state of severe denial of the reality of Lebanon and the Lebanese, and only see this as a new opportunity for blackmail, with the sole aim of keeping small power gains or even realizing personal dreams of later power. Unfortunately, it is a blackmail that goes beyond their political partners, to become a blackmail of the entire country, of the renewed international attention and of the livelihood and dignity of the Lebanese. Therefore, based on my firm belief that the most important thing at this point is to preserve the opportunity for Lebanon and the Lebanese to rebuild their capital and implement the well-known reforms that are long overdue, and to pave the way for the commitment of friends of the international community to help face the crisis and then invest in the return of growth, I declare that I am not a candidate to head the new government and I call on everyone to withdraw my name from the deliberations in this regard. The only starting point is for the President of the Republic to respect the constitution and immediately call for binding parliamentary consultations in accordance with Article 53, and that the heresy of composing the government before designating the Prime Minister ceases once and for all. Of course, with the Future parliamentary bloc, and in the parliamentary consultations that the constitution imposes without delay and that the Lebanese are impatiently awaiting, we will name the candidate that we consider competent and capable of forming a government guaranteeing the success of this unique and last opportunity for our country. We will also bet that this government is capable in form and substance of carrying out this mission, so that we cooperate with it in Parliament in order to carry out the reconstruction of Beirut, implement the necessary reforms and pave the way for our friends of the international community to support Lebanon at the humanitarian, economic, financial and investment levels.”

Riad Salameh: In Lebanon, depositors’ money is still available/Randa Takieddine/Arab News/August 25/2020

Riad Salameh told Arab News en Français he was in favor of the audit of the

Central Bank chief says he supports IMF involvement in Lebanon, Macron’s proposal for audit of BDL by Bank of France experts. Governor working on other means of financing, reassures depositors they ‘will get their money back, even if it takes time’

Riad Salameh has long been perceived as the strongman of Lebanon, the guardian of an economic model that has been the envy of many throughout the region. A skilled financier, he guaranteed the stability of the Lebanese pound for nearly 30 years and was awarded by the largest financial institutions. The banker saw his life change, however, with the October 2019 uprising and the economic collapse, which have mired the Land of the Cedars in turmoil. Since then, Salameh has come under fire. He is accused of having misused the money of Lebanon’s citizens by granting funds to the government, which have been wrongly managed by a political class corrupt to the bone.

Bank of France experts

In an exclusive interview with Arab News en Français, Salameh defended himself against these accusations, which he considers “unfair.” He claims to be in favor of the audit of the Banque du Liban (BDL) by experts from the Bank of France in order to advance negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The audit was proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron, who is visiting Lebanon after the explosion at the port of Beirut on Aug. 4. “An audit of the BDL, going back to 1993, was conducted by two international firms,” recalls Salameh. “The latest reports of this audit were sent to the IMF at the beginning of the negotiations. It is therefore important to acknowledge that this international audit exists, to dismiss any doubts about the way the BDL is managed. We welcome the proposal of the Bank of France to audit the BDL. The decision is the responsibility of the Bank of France, but we are ready to welcome their experts at their convenience.” On April 30, the government announced an economic recovery plan and requested assistance from the IMF, from which Beirut hopes to secure about $10 billion in aid. Lebanon initiated negotiations with the fund, but nearly three months later, the process stalled.

Lebanon’s new start needs to be locally led

Javier Solana/Arab News/August 25/2020

The writer Amin Maalouf, one of Beirut’s most celebrated sons, described the city as it was in the 1960s as “the intellectual capital of the Arab East,” and “the ideal place for maximum flowering and pluralism.” In his latest work, “The Shipwreck of Civilizations,” Maalouf charts the decline of that vibrant and resplendent Lebanon after it was razed by the same sectarianism that robbed so many countries in the Middle East of a promising future.

At the beginning of August, much of the Lebanese capital was literally razed by a huge explosion at its port. All indications suggest that the tragedy was the result of repeated negligence directly linked to the country’s political sclerosis. On the eve of the disaster, the Lebanese foreign minister had resigned, warning that narrow party interests threatened to turn Lebanon into a failed state. The explosion in Beirut is just the tip of the iceberg. Lebanon was already experiencing a deep economic and financial crisis that prompted a wave of protests last October against political deadlock, systemic corruption, and the continued interference of foreign powers. Since then, things have gone from bad to worse.

The UN World Food Program estimates that the price of food in Lebanon rose by 109 percent between October 2019 and June 2020. To this must be added the effects of the coronavirus disease, which have been aggravated by the chaos resulting from the explosion. Moreover, this troubled country has the highest number of refugees per capita in the world: Today, displaced Syrians make up 30 percent of the population. Lebanon is mired in its most serious crisis since the 1975-90 civil war, although in fact the country has never succeeded in closing the door on that bloody chapter. Its recent trajectory represents a paradigmatic case of what the British academic Mary Kaldor calls “new wars.” In this type of conflict, opposing factions seek to encourage extremist identities and perpetuate hostilities, because doing so gives them free rein to pursue extractive policies.

Lebanon’s situation demands that the West listen with humility and firmly support the demands of the local population.

Furthermore, factional leaders tend to use peace agreements to consolidate their positions of power and patronage networks, as was the case with the 1989 Taif Agreement that ended Lebanon’s civil war. This pact slightly modified the confessional quota system that has prevailed in the country’s public bodies since independence, hindering effective governance and the construction of a national identity. As Kaldor points out, peace agreements often don’t even end the violence. The emergence of Hezbollah during Lebanon’s post-civil war period attests to that. In short, Lebanon has been adrift for many years and the international community simply cannot look the other way. Let us not forget that the predecessor of the current Lebanese state was conceived precisely a century ago by the victorious powers of the First World War, following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The League of Nations placed Lebanon under a French mandate that lasted until 1943, and France maintains close relations with the country. French President Emmanuel Macron visited Beirut two days after the explosion and subsequently hosted a UN-backed virtual donor conference.

But the West has a broader historic responsibility that includes encouraging effective governance systems in Lebanon and the rest of the region. All too often, it has not been up to this task, resorting to interventionist excesses and paternalistic attitudes in its desire to assert control. The case of Libya, for example, shows how Western arrogance in backing regime change without viable reconstruction plans can contribute to state failure. Above all, any policy initiative undertaken on humanitarian grounds should respect a basic maxim of medicine: “First, do no harm.”

Lebanon’s situation demands that the West listen with humility and firmly support the demands of the local population, which is displaying a greater degree of cohesion than that sought by their leaders. Popular outrage following the explosion has already brought about the Lebanese government’s resignation, but that is not enough. Protesters are calling for a complete overhaul of the system, even by adopting slogans associated with the Arab Spring, although such an undertaking seems very complicated.

Neither Lebanon’s ruling class nor the country’s more influential neighbors will accept fundamental reform willingly, and the experience of the Arab Spring is far from encouraging. Only the Tunisian revolution led to democracy, and even that success has not been a panacea for the country’s problems. Nevertheless, any hope that Lebanon might have of rising from its ashes will lie, as in Tunisia, in allowing local voices to ring loud and dynamic social movements to develop from the bottom up.

*Javier Solana, a former EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Secretary-General of NATO, and Foreign Minister of Spain, is currently President of the EsadeGeo Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics and Distinguished Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In fifteen years between Hariri’s assassination and the Beirut explosion what did we learn?/Dr Amira Abo el-Fetouh/Middle East Monitor/August 25, 2020

There is no doubt that the verdict of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon regarding the assassination of Rafic Hariri, the former Prime Minister, shocked those searching for the truth. The court’s ruling was a disappointment, because it acquitted the leaders of the criminal Syrian regime and Hezbollah, and only convicted one of the four defendants who were brought to trial. Salim Ayyash, the former Hezbollah leader, was convicted in absentia of organising and carrying out the attack, when a suicide bomber killed Hariri and 21 others on 14 February 2005. Nobody knows Ayyash’s whereabouts, whether he is still alive or if Hezbollah killed him to destroy any evidence and conceal the truth.

The court did not close the case, which has left its mark on the Lebanese political system and almost led to civil war, with the Lebanese people split into two alliances, one represented by Hezbollah and its aides who are loyal to the Syrian regime, known as the March 8 Alliance, and the March 14 Alliance, consisting of the Future Movement and its fellow Maronites, the enemies of Syria such as the Lebanese Forces led by Samir Geagea, and the Aoun movement when General (now President) Michel Aoun returned from Paris and before his transformation into an ally of Hezbollah and Damascus.

This tribunal cost the Lebanese treasury nearly $1 billion, but it did not answer the most important question: who gave the order for Hariri’s assassination? Is it realistic to believe that Ayyash decided to act on his own volition? Logic dictates that someone else tasked him with this operation, and that this someone, whether a state, a movement or an individual, had a direct interest in killing the Lebanese Prime Minister. The political circumstances of the assassination were noted by the tribunal, which pointed out that Syria and Hezbollah may have had motives to eliminate Hariri and some of his political allies who were against them; in other words, that Syria and Hezbollah would benefit from killing Hariri. However, there is no physical evidence against either Syria or Hezbollah. This is often the case with political crimes that are tried in criminal courts, as if they were criminal offences, but there is a huge difference.

I was disappointed by the verdict, as I believed that the tribunal was the first stage of stripping away the immunity enjoyed by killers in Lebanon for too long; political assassinations have been taking place there for decades. This verdict was for a crime committed 15 years ago, and several similar crimes have since been committed in Beirut. Israel’s siege of the capital in 1982 killed more than 1,000 civilians, then Hezbollah invaded Beirut neighbourhoods in 2008, killing dozens. More recently we saw the terrible explosion that destroyed Beirut Port and a number of surrounding neighbourhoods, killing, wounding and displacing thousands. Meanwhile, Hezbollah is involved in the ongoing war in Syria. Waiting for the verdict brought to mind the struggle during which many people have paid the price for seeking justice.

Fifteen years have passed between the assassination of Hariri and the tribunal’s verdict; these years were full of change in both Lebanon and Syria. In July 2006 a war led to tremendous destruction in Lebanon, deemed necessary for Hezbollah and the Syrian regime to move beyond the repercussions of Hariri’s assassination and erase the remaining effects of the “Damascus Spring”. The outbreak of the Arab Spring revolutions in late 2010 and 2011, and the fall of the regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, as well as the arrival of the revolutionary wave in Syria in March 2011, put the Assad regime, Hezbollah and the entire Iranian axis back into defensive mode. It is possible that the massive explosion in Beirut at the beginning of August was an operation similar to the assassination of Hariri, with the same people behind it hoping to terrorise the Lebanese people just before the tribunal issued its verdict. It seems to me that those responsible in both cases have become known to everyone near and far.

Making Sense Of The Next Round Of Turmoil In Iraq And Lebanon/Alberto M. Fernandez/MEMRI Daily Brief /August 25/2020

Both Lebanon and Iraq have caught, beyond the usual routine of Middle East turmoil, the attention of the West in recent months. Lebanon, beset by Great Depression-level economic collapse, suffered the still-not-fully-explained Beirut Port explosion on August 4 that killed several hundred, injured 6,000, and destroyed part of the country’s capital city and principal port. As a result of the crisis, Lebanon’s government formally resigned and is in caretaker mode, awaiting the outcome of jockeying for ministerial seats by different factions. In Iraq, the year opened with the liquidation of Iranian terror master Qassim Soleimani in Baghdad, and in May 2020 the caretaker government of Adel Abdel Mahdi was finally replaced by a new government headed by Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, who visited Washington in August 2020 (his first foreign visit was to Iran in July).

Despite the reality that the governments of both countries are heavily influenced by Iran and its local proxies, the West has engaged. French President Emmanuel Macron visited Beirut in the immediate aftermath of the port explosion and has promised enhanced French engagement. Al-Kadhmi was warmly received in Washington, and his government signed agreements worth billions of dollars with American companies in the fields of oil, gas, and electricity.

The subtext in both situations – in two very different Middle East countries facing some superficially common issues – is of Western governments making good faith efforts to engage with counterparts. While Washington is more upbeat about the new Iraqi prime minister than about a new Lebanese government, in both cases the hope is that engagement and encouragement by the West can produce better results, for the local people and for Western interests, than past governments in Beirut and Baghdad have been able to deliver. But how realistic are these hopes for reform, and what are the immediate challenges to change?

On the surface, prospects seem better in Iraq. The economic situation is terrible, but nowhere near as catastrophic as Lebanon’s. Iraq has some money, while Lebanon has none. Al-Kadhimi is at least a fresh face on the scene, and has said some very good things about bringing perpetrators in the killing of activists to justice. Whether or not he can deliver is another question.

For Lebanon, sadly, the way forward seems to consist of forging a “national unity government” completely beholden to Hizbullah, or a more narrowly based “technocratic” government also beholden to Hizbullah. The Lebanese political cartel on which Hizbullah relies to implement its will seems confident that it can weather the disastrous social, economic, environmental, and political situation that it has engendered.

One similarity between the two countries is that despite the continued hegemony of Iran and its local minions, the disgust that led to constant demonstrations in both, from October 2019 and into 2020, by tens of thousands of people, especially young people, has not dissipated. These rallies were enduring enough to bring about the fall of the puppet government of the day, but not strong enough to bring about real change. As weak as the eventual result was, the demonstrations did represent an inchoate challenge to the Iran-controlled political order. The Iran-led response to even weak challenges has come and will continued to manifest itself in three ways: through violence, through political penetration, and through economic manipulation.

As Iraq’s new prime minister at least tries to make public efforts towards reform, Iran’s many proxies inside Iraq have escalated their activity, with targeted killings of activists, opinion makers, and journalists. The July 7 assassination of Hisham Al-Hashemi, who advised the government on terrorism, including on Iran-controlled death squads, was a direct message to Al-Kadhimi. Assassinations have continued into August 2020, aided and abetted by a massive pro-Iran militia/political party media apparatus inside Iraq built up over the past decade. Al-Kadhimi will be forced to either accommodate the death squads or confront them. There is a real public appetite in Iraq for a political leader that puts Iraq’s interests and sovereignty first, but it is still unclear if Al-Kadhimi can be that man, and, if he actually tries to do so, whether he will survive. In Lebanon, the trend towards violence and coercion is headed in a similar direction. There has been an increase in heavy-handed repression, assaults on journalists and demonstrators, and efforts to silence critical media voices such as Beirut’s MTV (Murr Television). The repression reached a new level of malevolent ridiculousness when Lebanese security forces hunted down, blindfolded, and extracted a confession and apology from one demonstrator, ironically a Lebanese Christian, who had disrespected a framed photo of Lebanon’s Christian President Michel Aoun during demonstrations. Some Lebanese fear that as Hizbullah becomes concerned that the people are losing their fear, another wave of assassinations of Hizbullah critics may come, as happened from 2004 to 2013 when prominent politicians, journalists, and security officials were targeted.

The threat of violence is always implicit. But Iran and its proxies rule in Lebanon and Iraq through their manipulation of politics and the electoral process. Particularly useful, especially in Lebanon, are non-Shia politicians who serve the interests of Iran. These Christian and Sunni enablers extend and disguise Iran’s reach into the political process. Any early elections that happen in either country – a demand by many earnest reformers – will be susceptible to manipulation by these corrupt political cartels in sync with Iran, to game an already skewed system in their favor.

As for economic manipulation, both Lebanon and Iraq are places where Iran and Hizbullah launder their money and also use ill-gotten gains and local government corruption to maintain their hegemony. What better way to care for an Iranian mole than to have him on the payroll of the state he is sent to infiltrate? The avarice of local elites works hand in glove to enrich themselves in the service of Iran’s larger objectives.

In the face of this Iranian straitjacket, what is the West to do? Is it better to walk away and cut our losses? Should the West, in this case France and the U.S., aggressively work towards reform? Are newer figures like Al-Kadhimi or wasted ones like Lebanon’s Saad Al-Hariri able to deliver anything of real value? Some voices in these countries criticize outsiders who call for an impossibly tough hardline in Lebanon and Iraq from far away, even though these same voices don’t seem to look askance at Western funding as long as there are few strings attached.

In my view, the West can and must engage, but needs to be much more cynical and transactional in its objectives. Too much “institution building,” “economic development,” and “process for the sake of process” can easily becloud our perspectives. Our main goal should be to deny Iran and its proxies the resources they need to rule, to raise the price of their hegemony. This could mean propping up elements of local society – independent media is one obvious sector – that can make useful contributions to making the price of hegemony higher. Putting pressure on enablers, those who provide convenient fig leaves for Iranian proxy rule, is another obvious gambit.

Absent a successful popular and violent uprising in Lebanon or Iraq against the Iranian satrapy – an outcome that seems very unlikely – the key to ending Iranian control of those states lies inside Iran itself, with the fall of that regime. In the meantime, keeping our objectives as hardnosed and tangible as possible seems the best choice.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI.

The American Mideast Coalition for Democracy (AMCD) Praises Trump Administration’s Historic Peace Deal between Israel and the UAE

التحالف الأمريكي الشرق أوسطي من أجل الديمقراطية يشيد بصفقة السلام التاريخية التي أبرمتها إدارة ترامب بين إسرائيل والإمارات

WASHINGTON, DC, USA, August 25/2020 / EINPresswire.com

The American Mideast Coalition for Democracy unequivocally supports President Trump’s bold and historic peace initiative to normalize relations between our two allies in the Middle East, Israel and the United Arab Emirates. Though our advisor, Dr. Walid Phares, was not standing behind the President when the deal was announced, he played a critical role in the development of its concept with the major actors going back to December 2015, when he and then-candidate Trump discussed the possibility of creating an Arab coalition to counter Iran along with Israel. In September, 2016, Dr. Phares then met with UAE’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan and then in November of that year, he met with the Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan. Later, he met with American Jewish leaders and Israeli scholars, as well as advisors to the Palestinian Authority visiting Washington. Always, Dr. Phares endeavored to advance the vision that he and President Trump developed back in 2015.

‘This agreement is destined to change the history of the Middle East,’ said AMCD co-chair Tom Harb. ‘After Obama signed that disastrous Iran deal, which betrayed all of our long-time allies in the region, it took some time to re-build the trust and confidence of the moderate Sunni states.’

‘Now that the UAE has come to the table, others will follow,’ continued AMCD co-chair John Hajjar. ‘A new strategic set of alliances in the Middle East will create the necessary peace and stability so that the people of the Middle East can begin to thrive and prosper. They have had enough of the death and destruction that radicalism brings. Young people are looking for a new direction. The people of the region are way ahead of their regimes and are ready for peace with Israel and a rejection of sectarianism. The UAE-Israel pact, although extremely important and historic, merely reflects this reality. Our communities will reflect this fact when we show our support at the signing ceremony in DC.”‘This deal is historic on many levels,’ declared Dr. M. Zuhdi Jasser, President and founder of the American Islamic Forum for Democracy. ‘You know it’s real when the imams inside the UAE are now giving sermons about the need for Arab and Muslim friendship with the Jewish community and with the state of Israel. Without that deep ideological shift and reform, similar deals would be meaningless. Mark today in history as a time when a tectonic shift happened in Arab-Israeli relations. Many with political agendas will try to minimize the relationship, yet other Arab states including Bahrain, Oman, Morocco, and even Saudi Arabia may be next. Naysayers need to be asked one question: If this is not a big deal, why has it not happened in the past? The fact that the Arab world’s greatest radicalizing influence on Muslims, the Islamist political movements from the Muslim Brotherhood, to Erdogan’s AKP to the Jama’at in Pakistan are upset speaks volumes to the long lasting impact of this deal.’

‘The death-dealing Iranian regime has been trying to export the revolution all over the Middle East by supporting radical Islamists of all stripes,’ added AMCD vice-chair Hossein Khorram. ‘They want to dominate the Middle East and to do that, they sew chaos and destruction at every opportunity. A stable coalition of moderate Arab states will eventually force them to become another nation among nations.’

‘The people of Iran are seeking peace and prosperity,’ said Sheikh Mohammad Al Hajj Hassan, who leads the Free Shia Movement and is chairman of the American Muslim Coalition. ‘They are furious that the Mullahs support terrorism to the tune of some $16 billion a year. This is money taken directly from the people of Iran where it is needed most. The people don’t want their money going to Hezbollah and Hamas, especially when the country is hurting so much economically.’

‘The deal with the UAE is a step in a broader process of Arab political recognition of Israel’s strategic, technological, and economic importance in the Persian Gulf zone, and across the Middle East,’ added Dr. Mordechai Nisan of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ‘Israel is rising to new heights in the historic saga of the re-constituted Jewish state.’AMCD is planning to hold a demonstration to support peace in the Middle East in Washington DC when the UAE’s Crown Prince comes to the White House to sign this historic agreement sometime in September.

Rebecca Bynum

The American Mideast Coalition for Democracy

+1 615-775-6801

Weeks after blast, Lebanon patronage system immune to reform/Samya Kullab/AP/August 25/2020

FILE – In this Aug. 6, 2020 file photo, French President Emmanuel Macron, second left, meets with Lebanese President Michel Aoun, second right, Lebanese Prime Minister Hassan Diab, right, and Lebanese Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, left, at the presidential palace, in Baabda east of Beirut. Beirut’s massive explosion fueled widespread anger at Lebanon’s ruling elite, whose corruption and negligence many blame for the disaster. Yet, three weeks later, the change many hoped for is nowhere in sight. The same politicians are negotiating among themselves over a new government.

Three weeks after a catastrophic explosion ripped through Beirut, killing nearly 200 people and rendering thousands homeless, the change many hoped for is nowhere in sight. Instead, activists said they are back to square one.

The same politicians whose corruption and negligence the public blames for the disaster are negotiating among themselves over forming a new government. Calls for early elections have petered out. To devastated Beirutis, still sweeping shards of glass and fixing broken homes, the blast revealed the extent to which an entrenched system of patronage remains impervious to reform.

In fact, the tools that the ruling elite have used to ensure a lock on power the past 30 years are only more powerful.

Rising poverty amid a severe economic crisis gives them greater leverage, with more people desperate for the income their patronage provides. Their grip on electoral politics was made tighter by an election law they passed in 2017, making it harder for independents to win seats. And there are armed groups affiliated with political parties.

“Basically, we have no way to force them out,” said Nizar Hassan, a civil activist and an organizer with LiHaqqi, a political movement active in the October mass anti-government protests.

Lebanon’s political parties are strictly sectarian, each rooted in one of the country’s multiple religious or ethnic communities. Most are headed by sectarian warlords from Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war — or their families — who stand at the top of powerful local business holdings. The factions pass out positions in government ministries and public institutions to their followers or carve out business sectors for them, ensuring their backing.

Opposition parties that cross sectarian lines with a reform agenda struggle to break that barrier. They are divided and lack grassroots support. They have also increasingly been met with brute force by security agencies.

Street protests have been dramatic. But the array of anti-government movements were not sizable enough to push for sea-change reforms, Hassan said.

“To seize the moment, you need people on grassroots level that are ready to announce they support it, and this doesn’t really exist in Lebanon,” he said.

Civic movements like LiHaqqi are not well-financed, face intimidation and can hardly afford to book airtime on mainstream channels, where elites are regular talking heads.

A sliver of hope is found in growing support from businessmen who once financed elites but have become increasingly frustrated, Hassan and other activists said.

Business owners began having a change of heart around the beginning of the year, as the economy deteriorated, hyperinflation flared and many people fell into poverty, said Paul Abi Nasr, a member of the Association of Lebanese Industrialists.

“The business community used to stay out of this from fear of retribution on their businesses,” he said. “But with the situation so dire already, a lot are now much more forthcoming.”

That has translated into a small stream of money to civil groups, though limited to covering organization and lobbying.

Industrialists and businessmen have helped prop up the patronage system, but most “were forced to play along,” Abi Nasr said. Politicians helped businesses in return for kickbacks and political support when needed.

Those in government who have witnessed the system from the inside maintain it cannot reform itself.

“People like me, after years in the world of government, basically feel that the system is immune to reform,” said Khalil Gebara, who left his job as an adviser to the Interior Ministry.

“But at the same point, the total collapse of the system will unleash a Pandora’s box of all kinds of sectarian conflicts,” said Gebara, now a consultant to the World Bank. “I don’t know what I should hope for.”

The wake-up call for Lebanon’s activists came not during the October uprising, when tens of thousands took to the streets in protest against the corrupt political class, but four years ago when Beirut held municipal elections.

It was the first time that a candidate slate emerging from a protest movement, Beirut Madinati, won in an electoral district. The small victory emboldened activists to look to polls to bring change.

It also spooked elites. The following year, they passed a new electoral law. It created a proportional representation system that ostensibly aimed to address demands of civil society and improve representation for minority sects.

But they “gerrymandered every aspect of the law in order to ensure that all political parties in power will be re-elected and none of the voices in the opposition could be,” said elections expert Amal Hamdan.

Under the law, a special formula determines the minimum threshold of votes for candidates to win seats. The factions worked to ensure those thresholds were high — ranging from 8% to 20% — and difficult for independents to gain, lawmakers and advisers with knowledge of the drafting of the law said.

In the south, for example. Shiite Hezbollah rejected proposals for a 5% threshold and arranged one as high as 20%, said Chantal Sarkis, an expert in political affairs and former adviser to Samir Geagea’s Lebanese Forces throughout negotiations over the law.

Activists like Hassan said the core problem lies with lack of grassroots support to initiate real political change. “When it comes to actual political dominance over the social fabric — everything is really manifest on local level.”

In his home district in the Chouf, where former warlord and Druze leader Walid Jumblatt is dominant, LiHaqqi supporters faced intimidation on the ground during the 2018 general election, Hassan said.

The father of one activist was sacked from his government job; mothers begged their activist children to stop canvassing in case powerful politicians got wind; others said they would vote for establishment parties because they wanted jobs. Not a single village allowed them to hold public events.

In the wake of the Aug. 4 explosion, when nearly 3,000 tons of improperly stored ammonium nitrate ignited at the Beirut port, political parties have set up field offices offering humanitarian and other assistance to victims.

Now with the falling Lebanese lira, Hassan fears establishment parties have more clout than before.

“It’s even cheaper for them to buy people.”

It’s time for Europe to follow Germany’s lead and ban Hezbollah/Jerusalem Post Editorial/August 25/2020

Germany justified the decision to ban the terrorist movement because of its call for armed struggle and rejection of Israel’s right to exist. The Jerusalem Post’s Benjamin Weinthal reported Sunday that Switzerland might follow the decision made in April by its neighbor Germany and ban all Hezbollah activities within its territory.

Last week, the Swiss Federal Council agreed to review a “Report on the activities of the Shi’ite Islamist Hezbollah in Switzerland.” The initiative was launched by Marianne Binder of the Christian Democratic People’s Party of Switzerland in June.

The proposed anti-Hezbollah legislation notes that Germany justified the decision to ban the terrorist movement because of its call for armed struggle and rejection of Israel’s right to exist.

The initiative reads: “The EU previously banned the [military] arm that engaged in terrorist activities. It is not known which activities Hezbollah is developing in Switzerland. In view of the neutrality of Switzerland, however, the activities of Hezbollah cannot be legitimized and a report is also advisable for reasons of security policy.”This highlights the ridiculous European Union approach to the terrorist organization, whose deadly tentacles have reached around the world. In July 2013, EU governments agreed to partially blacklist Hezbollah as a terrorist organization, but they made an artificial and dangerous distinction. The EU outlawed Hezbollah’s “military arm” but allowed its “political arm” to continue to operate, raise funds and recruit members. This financial pipeline and recruitment system keeps Hezbollah alive. It is absurd to promote the illusion that there is a difference between the “political” and “military” activities of an organization whose terrorists have caused hundreds of deaths and vast suffering globally. The terrorist organization itself does not make a distinction between its political and military operations.

As we noted after the welcome German decision in April, Hezbollah’s record as the perpetrator of major terrorist atrocities around the world has been known for decades. Its deadly acts include the bombings, orchestrated by Imad Mughniyeh, of the US Embassy and the military barracks in Beirut in 1983; the bombing attacks on the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires in 1992 and the AMIA Jewish center there in 1994; the bombing attack against US military forces stationed in Saudi Arabia in 1996; the murder of Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri; the bombing of a tour bus carrying Israeli tourists in Burgas, Bulgaria, in 2012; not to mention the myriad attacks against, and kidnappings of, Israelis, Europeans and Americans; its role in provoking the Second Lebanon War in 2006 and its part in the Syrian civil war, where it helped Iran – its sponsor – create a corridor of terrorism from Tehran to Beirut.

The devastating explosion that destroyed the Port of Beirut earlier this month – killing at least 180 people and leaving a quarter of a million homeless – can also be pinned on Hezbollah. Although the exact cause is not yet certain, it is clear that Hezbollah is responsible either through negligence, corruption or stockpiling of explosive material with malevolent intent, or a combination of all these factors.

Hezbollah’s efforts to obtain precision-guided missiles and the discovery of the warren of terrorist attack tunnels crossing from Lebanon into Israel are additional indications that it has not given up its deadly goals.

For years, the US and Israel urged Europe to ban Hezbollah, but it was only after Hezbollah carried out the attack in Burgas that the EU moved to partially ban the organization. This newspaper has reported on many Hezbollah activities in Europe and its open support of terrorism. It has also been reported that the Mossad provided intelligence that helped thwart attacks on European soil.

In Europe, apart from Germany, the UK, Lithuania and the Netherlands have also outlawed Hezbollah in its entirety. Elsewhere, the Arab League, Israel, the US, Canada and many Latin American countries have designated Hezbollah’s entire entity a terrorist movement.

We hope that Switzerland follows suit. A full ban on Hezbollah everywhere is long overdue. It is not only Israel that is at risk. Hezbollah’s terrorism – funded by its Iranian sponsors – affects the whole world. This is not just an Israeli concern. Terrorism cannot be tackled in halves, with artificial distinctions between “military” and “political” wings. The only way to stop Hezbollah is to universally recognize that it is a terrorist organization whose heinous acts cannot be tolerated anywhere in the world.

City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut/Robyn Creswell/Reviewed by Franck Salameh/Middle East Quarterly/Summer 2020

Writing in 1968 of a city of “varied vertigos,” Franco-Lebanese poet Nadia Tuéni described her native Beirut as both a courtesan sophist and sainted,[1] “A pink merchant city, like a fleet of ships adrift, scanning the horizons for the warmth of a seaport.” Tuéni’s Beirut was the “Orient’s very last shrine, where mankind could still adorn its kind with a mantle of light,”[2] burning away regional obscurantism and gloom.

Creswell’s City of Beginnings is a story of that irreverent, incandescent Beirut, of a coterie of young Arabophone writers, cosmopolitan iconoclasts who made that Beirut of multiple identities home. Beirut was a crucible for their cultural and political rivalries, a shrine for impieties suppressed elsewhere in the Middle East but given sanctuary in a Levantine city stalled between World War II and the beginnings of the 1975 Lebanese civil war. In that sense, City of Beginnings is a book of mutiny and mutineers, who shunned the Arab world’s conformist proclivities in mores, language, cultural rituals, and intellectual production.

With an intellectual historian’s sensitivity and a firm grasp of mid-twentieth century Lebanon’s languages and worldviews, Creswell’s focus is the “modernism” emanating from Beirut’s Arabic-language literary journal Shi’r and its luminaries: Greek Orthodox Lebanese Youssef al-Khal (1917-87) and Syrian heterodox Adonis (b. 1930.)

Like many of their contemporaries, whether Shi’r collaborators or Francophone Lebanese nationalists apprehensive of Arabism, Adonis and Khal spurned Arab national orthodoxies, espoused cosmopolitanisms, and called for “Eastern,” “Oriental,” and “Levantine” rebirth and renewal rather than then-normative allegiance to Arabism. They valorized pagan, pre-Arab, pre-Muslim progenitors—including Canaanite-Phoenician seafarers of classical antiquity—and spoke of the extinction of Arab civilization even as they sought to restore its belles lettres.

Arabism’s tyranny had staying power, and the iconoclasts of Shi’r ran out of breath.

But Arabism’s tyranny had staying power, and the iconoclasts of Shi’r ran out of breath. This resignation played out in early 1970s Beirut, in the self-immolation of Shi’r’s vaunted “learned republic,” that had once married cultural and communal pluralism to political exceptionalism, irreverence, and a turbulent, pedigreed oriental Christendom, naturally predisposed to peculiarities, unlike those of the Arab hinterland.[3]

In the view of Kamal Jumblatt, founder of the Lebanese Progressive Socialist Party, the Beirut of Shi’r had a natural vocation: transmitting to the West the faintest pulsations of the East. This was the city’s immemorial calling, to “interpret the life ripples of the Mediterranean … to the Muslim realms of sands and mosques and sun.”[4] But there comes a time when a city and its people can no longer give. In Beirut’s chaotic clash of ideas, and later, orgies of violence, Adonis watched all the grand ideas emanating from Arabism, Syrianism, and Lebanese nationalism end up in bloodshed and wars of extermination. In the mid-1980s, the writers of Shi’r, adopted sons of Beirut, no longer recognized the city that had once nurtured them.

And yet, Shi’r predicted its adoptive parent’s demise. Adonis in the late 1960s prophesied an apocalyptic end resembling Beirut of a decade or two later. He even depicted a self-immolating Beirut as harbinger of things to come elsewhere in the Middle East: Syria for instance, in these sad decades of the twenty-first century, child of an “Arab Spring” that never was. In his “Elegies for the Times at Hand,” one of his most haunting poems written in the late 1950s, Adonis spoke of tyranny, silence, destruction, and exile as renditions of the Arabs’ nightmares and realities.

Speaking of Syria’s own slide into war in 2011, Adonis indicted Arabism as a desecration of the Middle East’s diversity, surrendering its richness “to a single, one-dimensional linguistic, cultural, racial, and religious Arabism.”[5] More nuanced in his charges against Arabism, Amin Maalouf, a Franco-Lebanese novelist, spoke of his Parisian neighbor Adonis’s Beiruti cosmopolitanism as a notion

that brings a scornful smile to the lips of the ignorant … partisans of triumphalist barbarity … children of arrogant tribes who make battle in the name of the one and only God, and who know no worse enemy than our subtle, fluid identities.[6]

Creswell’s City of Beginnings is about those ideas of a capacious, Levantine port-city, a Beirut that once condensed the dreams of a generation of intellectuals and laymen, offered a crossroads of ideas, identities, and influences, and provided a laboratory of diversity, rebirths, and renewals—ultimately aborted—but which deserve being revisited. It is a snapshot of “another Middle East” that once was and a blueprint of a “Middle East yet to come,” seldom recalled by area specialists, students, scholars, and policy makers still smitten by Arabist uniformity.

To the student of the Middle East, Arabic literature, literary modernism, or Near Eastern intellectual history, this book is a learned, nuanced, and deeply searching guide.

Franck Salameh is a professor of Near Eastern Studies at Boston College where he teaches in the Department of Slavic and Eastern Languages and Literatures. He is the author, most recently, of The Other Middle East (Yale, 2017) and Lebanon’s Jewish Community (Palgrave, 2019).

[1] Nadia Tuéni, Liban: Vingt poèmes pour un amour (1979) in Œuvres poétiques complètes (Beirut, Leb.: Dar al-Nahar, 1986), p. 278.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Samir Kassir, Histoire de Beyrouth (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2003), p. 610.

[4] Quoted by Camille Abousouan in “Présentation,” Les Cahiers de l’Est (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1945), p. 3.

[5] Adonis, “Risala maftuha ila ar-Ra’is Bashar al-Asad: al-insan, huquqihi wa hurriyatihi, aw al-hawiya,” as-Safir (Beirut), June 14, 2011.

[6] Amin Maalouf, Les désorientés (Paris: Grasset, 2012), p. 36.

Syrians Lose Children, Homes and Jobs in Beirut Blast/Agence France Presse/Naharnet/August 25/2020

Ahmad had saved his family from Syria’s brutal war by bringing them to Lebanon, but then Beirut’s massive blast ripped his wife and two of their daughters away forever. Weeks later, looking at the rubble of his former home near the port, he recounted how the explosion in one horrific moment upended his life.

“I feel like I’ve lost my mind. I closed my eyes, and when I opened them everything around me had changed,” said the man, aged in his forties. “I lost everything in an instant. We were a family of six people, but now it’s just me and my two daughters.” Ahmad, from the Syrian province of Idlib, had worked hard in Lebanon for years, holding various jobs to send money home. Three years into Syria’s war, as fighting intensified in 2014, he decided to bring his family to Lebanon. Then the August 4 disaster struck, Lebanon’s worst peace-time disaster. After hundreds of tonnes of ammonium nitrate exploded at the Beirut port and sent shockwaves across the city, Ahmad rushed home to Beirut’s Karantina neighbourhood. He was first to find the body of his 22-year-old daughter Latifa, who had been thrown against what remained of a wall. With the help of neighbours and civil defence workers, he also pulled from the rubble the bodies of his 13-year-old daughter Joud and 40-year-old wife Khalidiyeh. They managed to save another daughter, Diana, 17, after she had been trapped for 11 hours under the debris, screaming as both her legs were severely injured. Only 14-year-old Dima survived unscathed and now spends her days by Diana’s hospital bedside.

– ‘Somewhere safe’ –

Ahmad says all he hopes for today is to leave. “I wouldn’t dream of returning to Syria while it’s not safe,” he said. “I’m trying to find a way to travel abroad,” he said. “I want to live somewhere safe with them.”The working class neighbourhood of Karantina was one of the most damaged by the blast that killed more than 181 people, wounded thousands and ravaged large parts of the city. Twenty-year-old Syrian Uday Qattan and his extended family, most of whom have lived in Lebanon for years and worked at the port, also lost their home. In what remained of it, walls have cracked or collapsed, ceilings caved in, and most furniture has been destroyed except for the odd television or mirror. An adjacent shack shared by the bachelors in the family has been reduced to splintered wood. After the explosion, which the family says they survived by a “miracle”, the married men sent their wives to other parts of Lebanon to live with relatives. Remaining family members now sleep in the courtyard in between the rubble, behind a washing line strung up with clothes. “We no longer have any work or home,” Qattan said. “We sit here all day with nothing to do.” They cannot return to Syria, where they lost their homes in Hama province in the war, and risk being detained over dodging military service.

– ‘No food, no country’ –

Qattan joined his relatives a year ago from Syria’s Idlib, where a fragile ceasefire has barely stemmed a regime offensive on a rebel bastion. But he and his family say the Beirut blast was like nothing they even witnessed during the war. “In Syria, if we heard the sound of a war plane, we’d hide then stand back up after the strike, brush off the dust, and continue our lives,” Qattan said. “Here a single explosion has wrecked everything around us.”Syria’s embassy has said 43 of its nationals were among those killed in the blast. The United Nations says 13 refugees lost their lives, while 59 are missing. It is not clear how many were Syrian. Syrians had long sought employment in Lebanon before the war started in 2011 and sent 1.5 million Syrians fleeing for shelter across the border. In Karantina, other Syrians, both those long-established and newcomers, recounted their experiences the day of the blast. With Syria’s conflict, then the blast in already economically suffering Lebanon, “it’s really been a double blow to the head,” said one of them. As they talked, an aid truck pulled up, and they rushed out to receive their portions: pasta, biscuits, a few canned goods and water. Twenty-one-year-old Nasr said that Syrians had been denied emergency aid deliveries on some occasions, being told that the packages were only for Lebanese. “We used to work just enough to eat and drink, and pay rent,” he said. “Now there is no food, drink or money, and no country — in Syria or in Lebanon.”

After Beirut Blast, Foreign Workers Beg to Go Home/Agence France Presse/Naharnet/August 24/2020

After struggling first through Lebanon’s economic crisis and then the coronavirus pandemic, Ethiopian worker Tarik Kebeda said the deadly blast that ripped through her Beirut home was the final straw. Inside the small house she shares with four friends, she pointed to the window frames covered by sheets, because the glass was smashed out by the August 4 explosion. They had already lost their jobs — as domestic workers, or in supermarkets or restaurants — but now their home too is at risk. “I’m scared to sleep here,” the 22-year old said, showing the deep cracks running down the bedroom’s walls, saying she feared the building “will collapse on top of us”. Thousands of foreign workers were already stranded in Lebanon, after months of dollar shortages and then the coronavirus pandemic. Then came the blast in Beirut’s port that killed more than 181 people, wounded thousands and devastated swathes of the city. Many say it was just one disaster too many, and now they need to leave. “I love Lebanon, but I don’t want to live here anymore,” Kebeda said. “There’s no more work. How will I eat?”Some foreign workers also say they feel sidelined by aid efforts. In the poor neighbourhood of Karantina, Kebeda’s neighbour Hana claimed aid workers sometimes put fellow Lebanese first. Next door, 31-year-old Romane Abera recounted how she hid beneath a parked car to hide from the explosion. “Once, a truck came to distribute food boxes but they said: ‘Only give them to the Lebanese’,” Hana said.Today her damaged home is barely held up by scaffolding, with hot gusts of summer air sweeping through a huge hole in the wall.

Hammer protest

“I wish Lebanon could go back to how it was before,” said Abera, who left behind her baby boy in Ethiopia and recently lost her job. Hundreds of thousands of migrant workers of multiple nationalities — including at least 250,000 housekeepers and carers — toil in Lebanon for cash to send home. They enter Lebanon under a controversial sponsorship system called “kafala”, which has been repeatedly denounced by rights groups as enabling a wide range of abuses. Under kafala, a worker cannot terminate their contract without the permission of their employer or they will lose their legal immigration status. Many foreign workers have reached breaking point. Outside the Gambian consulate in Beirut, around 30 Gambian women clamoured for help. “We’re like slaves,” one protester shouted. “We are not treated well, and the racism here is very high.” Zeina Ammar, from Lebanon’s Anti-Racism Movement (ARM) organisation, urged countries to fund evacuations, and provide travel documents when needed. “We want to go home,” they chanted. Some threw handfuls of dirt towards the building, while others hit its door with hammers. “It should be a systematic, unconditional provision of laissez-passer to absolutely everyone in order to save their lives,” she said.

‘Systematically dehumanised’

After the port blast, Lebanese shared videos online celebrating the courage of migrant workers helping with clean-up efforts in the streets, as well as footage of a housekeeper on August 4 diving to rescue a toddler from an imploding window. But ARM says not enough attention is being given to the migrants who fell victim to the blast. “The official tally of the deceased and the missing remains incomplete, excluding primarily people of non-Lebanese origin,” ARM said. “Migrant workers and refugees are systematically dehumanised and marginalised in Lebanon, in life as in death.”Outside the Kenyan consulate, dozens of women said they had been holding a sit-in since August 10 to demand their repatriation. Among them, a 21-year-old recounted escaping abusive employers, only to be injured and see her home destroyed in this month’s explosion.

The consulate said efforts were underway to fly those who wished back home, but demonstrators complained of inaction. Another woman said her employers had dumped her at the consulate just days after the blast without a passport or the salary she was owed, accusing her of being too ill to work. A fellow protester, 27-year-old Emily, was incensed.”Who throws a sick woman on the streets at night?” she asked, with another woman’s five-month-year-old baby lying beside her.”We just need help to go back home. Only that.”

Occupation… Electronic Justice and the Mirage of an International Community

Sam Menassa/Asharq Al-Awsat newspaper/August, 24/2020

…Now that the Special Tribunal for Lebanon has finally issued its verdict on the assassination of ex-PM Rafik Hariri and his companions, no one can continue to turn a blind eye any longer.

A military official in Hezbollah by the name of Salim Ayyash has been found guilty of killing a Lebanese prime minister, a hard fact that cannot be blown off from today onwards, and any scenario that ignores it has no worth in politics, security, law or the balance of international or Lebanese justice.

However, despite this fact, and without getting into its legal dimensions which I will leave to experts, the verdict that came 15 years after the earthquake that had shaken Lebanon in 2005, allowed, because of its form and content, commentators and pundits of the “axis of resistance” to promote what they now consider facts and build on them. Four are most prominent.

First, the verdict acquitted Syria, or, more accurately, the court was unable, with conclusive legal evidence, to confirm its ties to the crime.

Secondly, the verdict acquitted Hezbollah’s leadership, or, more accurately, the court could not find evidence to prove that the party had been involved beyond reasonable doubt.

Third, based on the acquittal of Syria and the impossibility of Hezbollah having carried out an act of this magnitude and seriousness without the former’s knowledge, the commentators hold Israel responsible for Hariri’s assassination and link the crime to the war that broke out afterward in Syria. Their analysis can ever go as far as to also connect it to the explosion at the Port of Beirut.

Fourth, they considered the only person that the court had convicted of the assassination, Salim Ayyash, a bird flying away from it flock.

Without getting into the court’s precision, objectivity and professionalism, it is worth mentioning that the verdict was based on communication network data gathered by a Lebanese Captain, Wissam Eid, who had been assassinated in one of a series of murders that killed off a select group of Lebanese figures opposed to the Assad regime and Hezbollah, and the investigation did not subsequently add anything new to that data.

Given that the Tribunal is an independent judicial body that includes Lebanese and international judges, and is not a United Nations court and does not have the authority to charge states, bodies or parties, this long-awaited ruling reiterated to skeptics the limits of the international community, represented by the United Nations and its agencies.

This came as a shock to the Lebanese, especially in light of the country’s current situation, magnifying their disappointments that stem from many other issues, some old and some new. The most prominent of these issues are chronic political gridlock, the unprecedented economic and financial collapse and the horrors of the Beirut Port blast and its humanitarian and political repercussions, especially the fall of Hassan Diab’s government and the subsequent hard-line position declared by Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah, with his rejection of any neutral government that can implement the reforms demanded by the international community.

All of this brings us back to the real problem in Lebanon; the Lebanese state that has existed, in theory, since the country’s independence in 1943, is being eaten away to the advantage of an alternative state that is being built. While so-called demands for reform, ending corruption and improving public administration, it has become glaringly apparent, aim to shift attention away from the source of all of these problems. That is, the fact that the country has been under occupation for six decades.

A quick overview of Lebanon’s modern history, from the 1960s onwards, shows us that throughout the period stretching from the Cairo Agreement in 1969 until the explosion at the port, Lebanese crises were being addressed, or sought to be addressed, through attempts at political reform that enhances political participation and economic reform that eliminates corruption and squander.

The same demands are currently being raised by both the local and external parties. The unequivocal reality of the situation, nonetheless, is that the causes of the actual and real crises were and still are the state’s weakness, or even collapse, in the face of foreign presence on Lebanese land and the roles that have been played by the different parties.

At the end of the sixties, it had been manifested in the Palestine Liberation Organization and its domination over factions that benefited from the rifts in the ranks of the Lebanese. At the time, the civil war began with the Two Years War and what had been called the transitory phase of the Arab nationalist and progressive parties’ front, which aimed to reform the regime by curtailing the influence of what had been known as Political Maronitism to ensure greater powers for the premiership, cancel political sectarianism and achieve other objectives.

During the same period, towards the end of President Suleiman Franjieh’s term in 1976 in particular, the constitutional document appeared, another document for reform. After the Israeli invasion and the subsequent Palestinian exit and the entry of Syrian forces in their place, while the Syrian and Israeli troops were still present in the country, the Geneva Conference of 1983 and then the Lausanne Conference of 1984 also called for reforming the political system, as the war had been ongoing.

Later there came the tripartite agreement of 1985 and the Taef Agreement of 1989, which theoretically established the Second Republic through a reform of the political system. After Syria’s exit and the Iranian occupation that took its place through its ally Hezbollah, the Doha Agreement was signed in 2008.

During all these stages, demands for political change and reform or reformulating political participation served as a smokescreen that obscured the reality of the political turmoil and conflicts in Lebanon. The state’s weakness at first, which eventually led to its complete absence due to the various foreign occupiers who have been making the decisions since the 1960s, has allowed for corruption to ravage the country as it does today.

Mismanagement, neglect, chaos and smuggling are rampant. This does not negate the need; indeed, there is an urgent need for reform and good governance. However, we are still being sucked into the same vortex; we are preoccupying ourselves with clothing though the body is dead, with reforms in a country that does not exist. This has pushed some to consider an international management for the Lebanese crisis as the country’s only hope for escaping the abyss.

The Tribunal’s verdict came to affirm that these hopes are a mirage, as it demonstrated the international indifference to Lebanon’s fate despite all the noise around it today.

It also reiterated the international community’s inability to help or save Lebanon at this stage, which cannot be surmounted with any political reform or settlement. If the ruling were such to avoid straining the country further by referring to the real criminal, because of powerful countries’ apprehensions about a potentially explosive conflict, the decision nonetheless failed to eliminate this specter because it dashed the hopes of a substantial segment of Lebanese society and turned it into a time bomb that could explode at any moment as its sense of marginalization and vulnerability continues to grow.

The most disappointing aspect of the ruling is that it showed that the Western world, which has been relied upon, is today run by craftsmen and technocrats whose decisions are driven by modern technology and computers and lack common sense. This is precisely the logic the international tribunal used to come to its verdict; it claimed the evidence is legally considered circumstantial without considering the political and geostrategic incentives to be conclusive evidence for the decision on this terrorist act…

The West lives in the ambiguous virtual world of miniscreens and focuses its attention on consumption and people’s daily needs. On the other side of the world, “ideologues” have been hijacking the real world for more than two decades.

Western leaders and elites argue on social media and electronic platforms to compensate for not boldly interacting with events to find creative solutions they are capable of. Instead, they waste their capabilities on luxuries and entertainment…

Lebanese businesses rebel against lockdown

Najia Housari/Arab News/August 24/2020

BEIRUT: The owners of stores, restaurants and other businesses in Beirut and other cities in Lebanon on Monday rebelled against a government-imposed lockdown intended to slow the spread of the coronavirus. They said they will reopen from Wednesday.

The defiant move reflects growing concern about the political stalemate in efforts to form a new government, and the worsening financial crisis. Riad Salameh, governor of the Banque du Liban, Lebanon’s central bank, reportedly told President Michel Aoun, caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab and caretaker Minister of Finance Ghazi Wazni last week that there is only enough cash in reserve to fund subsidies of basic items such as bread, fuel and medicines for three months. It has $19.6 billion available, $17.5 billion of which must be kept to cover a portion of deposits by bank customers. This leaves $2.1 billion for subsidies, which cost $700 million a month. This financial drought has been caused by declines in remittances from expatriates, which reached $7.5 billion in 2019, the collapse of tourism, worth up to $7 billion a year, and a lack of investment.

Nicolas Chammas, the chairman of Beirut Merchants Association, announced a “total rejection of the lockdown in light of the failure of the state to provide alternative income for the people, and the restrictions on access to money deposited in banks.”

He also criticized the lack of government action to help businesses and added: “We used to say 25 percent of shops will close by the end of this year — now we will be lucky if 25 percent of commercial establishments survive until the end of the year.”

Chamas called for the formation of “a national salvation government quickly” and added: “We refuse to turn into a relief economy because we are not beggar people; we want a productive economy.”

The previous government resigned this month amid public anger over the explosion that destroyed Beirut’s port on Aug. 4. Many analysts predict the financial situation will get worse before it gets better. The Lebanese currency has lost 85 percent of its value, inflation is 90 percent, and a second wave of the coronavirus is adding to the problems. As more people lose their jobs, Lebanon does not have a social safety net to help them. “I do not understand how the politicians have not yet been provoked by the fact that the central bank’s hard-currency reserves have hit rock bottom and they are not moving in the direction of immediate solutions,” said Bechara Asmar, the head of the General Labor Union. “They must form a government of competent people who can decide on the beginning of a strategy.

“The first way to address the problem is to form a government with a minimum level of understanding of economic policy. It is unacceptable that leaders elected by the people do not speak to each other.”

A source at the Ministry of Finance said: “A set of measures could have been taken to address the economic collapse the country is facing … but the problem is that no one in authority wants to make any concessions.”

To recover, Lebanon will need to borrow billions of dollars from the international community, and the main condition for such a loan is sweeping economic reforms. On Monday, Wazni delivered to Aoun a contract with management consultancy Alvarez and Marsal. It will carry out a forensic audit of the accounts at the central bank. Wazni said he expects the contract to be signed in a few days and the audit would begin four or five days later. An initial audit report would be published within 10 weeks.

“The president is keen to ensure the audit includes all public institutions and is not limited to the accounts of the central bank,” he added.

US Seeking to Reduce Number of UNIFIL Troops, Stop Hezbollah Violations

New York- Ali Barda/Asharq Al Awsat/August 24/2020

France distributed a draft resolution to members of the Security Council, authorizing the extension of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) until the end of August 2021, in order to continue the implementation of UNSC Resolution 1701.

The French draft resolution included amendments that diplomats described as “balanced”, to counter the pressure exerted by the United States to introduce changes to the mandate of the international forces.

The US is seeking to reduce the number of UNIFIL troops by a third and extending their mandate for six months instead of a full year, in addition to granting the international mission more powers to prevent militants and illegal weapons from circulating in its area of operations between the Blue Line and the Litani River. Asharq al-Awsat obtained the second draft of the resolution, which was distributed to the council members after three rounds of negotiations.

“Until the last round of negotiations, the US negotiator was insisting on three amendments: reducing the UNIFIL troops from 15,000 to 10,000, decreasing the extension period from 12 months to six months, and preventing (Hezbollah) from continuing its violations of Resolution 1701,” a diplomat told Asharq Al-Awsat.UNIFIL’s current mandate expires on August 31. Contrary to the US desire, the French negotiators distributed the second draft of the 29-paragraph draft-resolution, which “extends the current mandate of the UNIFIL until August 31, 2021,” welcomes “the expansion of coordinated activities between UNIFIL and the Lebanese army, and calls for increased cooperation without compromising the UNIFIL mandate.”It also reiterated the Security Council’s call on the Lebanese government to “submit a plan to increase its naval capabilities as soon as possible… with the aim of reducing the naval force of UNIFIL and transferring its responsibilities to the Lebanese Army.”A new paragraph was added to the draft stating that the Council welcomed the report of the Secretary-General (of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres) regarding the assessment of the continuity of UNIFIL resources and its options to improve the efficiency and coordination between UNIFIL and the Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator in Lebanon, taking into account the maximum number of forces and the civilian component within the UNIFIL. The draft resolution called for “an increase in international support for the Lebanese army and all the state’s security institutions” and denounced “all violations of the Blue Line.”It also urged all parties “to respect the cessation of hostilities, to prevent any violation of the Blue Line, and to cooperate fully with the United Nations and UNIFIL.”While the Security Council welcomes the “constructive role played by the tripartite mechanism” between Lebanon, the United Nations, and Israel in “facilitating coordination and de-escalating tensions”, it encourages “UNIFIL, in close coordination with the parties, to implement measures to further enhance the capabilities of the tripartite mechanism, including the establishment of additional sub-committees,” according to the French draft resolution.