هالة القدسية سقطت وهكذا خسر حزب الله الكثير من رصيده في الشارع اللبناني

ربيكا كولارد/فورين بوليسي/29 تشرين الثاني/2019

Untouchable No More: Hezbollah’s Fading Reputation

Rebecca Collard/Foreign Policy/November 29/2019

As Hezbollah sides with Lebanon’s political elite, protesters in Beirut are increasingly willing to criticize it.

BEIRUT—It was the sort of chant that, only a month or so ago, would have been all but unthinkable in Lebanon. “Terrorists, terrorists, Hezbollah are terrorists,” yelled some of the hundreds of anti-government protesters who stood on a main road in Beirut early Monday morning, in a tense standoff with supporters of Hezbollah and another Shiite party, the Amal Movement.

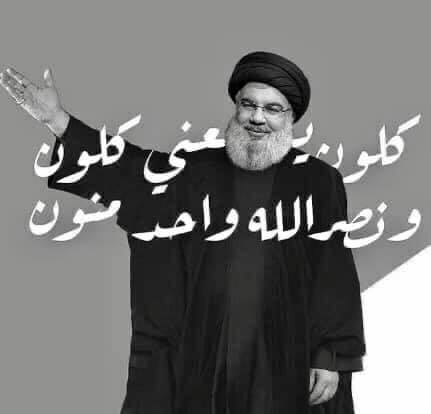

Other protesters told the chanters to stop, but as widespread economic discontent and anger engulf Lebanon—and with Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah defending the government—the sanctity around Hezbollah’s reputation is clearly broken.

“Hezbollah is being seen as part and parcel [of] the main hurdle to change in Lebanon,” said Mohanad Hage Ali, a fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center.

The demonstrations have been mostly peaceful and unilaterally against the whole ruling class—all sects, all political parties. And until recently Nasrallah, who doesn’t have an official government position, was seen as above the endemic corruption that has helped push the country toward a collapse, particularly among Hezbollah’s Shiite support base. Hezbollah’s expulsion of Israeli troops from Lebanese territory in 2000 earned the group the moniker “the resistance” among Lebanese of all sects and political affiliations. Even after the 2006 war, which left swaths of Lebanon in ruins, the group enjoyed popular support for what many here saw as a victory against Israeli aggression by defenders of the country. In May 2008, Hezbollah fighters took over central Beirut after the government threatened to shut down the group’s telecommunications network and remove an ally in charge of airport security, pointing their weapons inside rather than toward the border for the first time.

And as Hezbollah sent thousands of fighters across the border to fight in Syria in support of President Bashar al-Assad in 2013, more people questioned exactly whom Hezbollah was defending. The group’s reputation has been fading further since the first days of protests in mid-October, which saw large crowds take to the streets in primarily Shiite areas such as Tyre and Nabatieh. Suddenly, with demonstrators there shouting similar anti-government slogans as protesters in Beirut—who want all the current sectarian political leaders gone and new elections under a new system—Hezbollah found itself part of the targeted establishment. The protests are seen as a direct challenge to the gains made by Hezbollah in the 2018 elections and a threat to the organization’s foreign-policy agenda, said Hage Ali.

This week, facing down two thick rows of Lebanese army and riot police on pavement littered with rocks and sticks, some demonstrators complained that Hezbollah’s agenda is not really about building up Lebanon; instead, it goes through Damascus to Baghdad and on to Tehran. Like some of the rising protests in neighboring Iraq, the often youthful demonstrators are intent on calling out Iranian influence in particular.

“Here is Lebanon, not Iran,” some protesters chanted on Monday.

When Nasrallah insisted the Lebanese government should not step down, amid the early demonstrations in October, to many protesters it felt like he was part of the problem.

“It was a ‘reality bites’ moment,” Carnegie’s Hage Ali said. “For Lebanese Shiites who joined the protest movement, it was a shock—why is Hezbollah standing on guard for the status quo that is extremely corrupt and taking the country to a financial and economic crisis?”

Nasrallah attempted to discredit the protesters, implying they were funded by foreign embassies. The protesters laughed it off, and several journalists resigned from Al-Akhbar, a publication usually supportive of Hezbollah’s position.

“They are just trying to keep the system,” said a protester named Baha Yahya, as he waited on a side road for a barrage of tear gas, fired by the army, to clear. “And all we want is to remove the system. That’s what this is all about.”

In the past Hezbollah has managed to avoid most direct criticism of its ties to Tehran and Syria. For decades, Lebanon’s warlords, then political elite, have been propped up by regional and international powers, and the protesters have railed against this foreign meddling in their country. But the protesters have been careful not to single out any one group, and until recently there has been scarce mention of Hezbollah’s Iranian-supplied weapons, which outgun the country’s national army—ironically now holding back the group’s supporters.

Last week, as thousands of people took to the streets of Iran after a hike in the price of fuel there, protesters in downtown Beirut sought some common cause with them, chanting: “From Tehran to Beirut, one revolution that won’t die.”

And Hezbollah supporters are fighting back. Hoisting the flags of Hezbollah and Amal, counterprotesters this week shouted sectarian slogans like “Shiite, Shiite, Shiite” and affirmed allegiance to Nasrallah and Nabih Berri, the head of the Amal Movement and speaker of the Lebanese Parliament.

The anti-government protesters responded with chants of “the people are one”—and then broke into the national anthem.

It’s not exactly clear how the confrontation started on Sunday night, but what is clear is that it has raised fears of a violent escalation to Lebanon’s 6-week-old rebellion against poor sectarian governance and put a further stain on Hezbollah’s image as the country’s defender.

This same bit of road was the front line for much of Lebanon’s civil war. Everyone here knows that, but most of the protesters are too young to personally remember the snipers and checkpoints that controlled it.

Some of the Hezbollah and Amal supporters managed to break through the line, charging the protesters and sending them running down side streets, past buildings still pockmarked from civil war fighting.

“They can reach us if they want,” Yahya said of the Hezbollah and Amal supporters as he waited on a side road. “But they don’t want that. They just want to scare us.”

The mostly male protesters returned with tree branches and sticks. Both sides tried to lob rocks across the no man’s land created by rows of security forces.

Hezbollah blamed a car accident early Monday morning on the protesters’ roadblocks. A video of the incident shows a car hitting an obstacle in the middle of seemingly empty road. There is not a protester in sight. Some saw it as an attempt to portray the protests as a security threat. Hundreds of people turned out for a vigil on Monday evening hoisting Hezbollah and Amal flags and chanting party and sectarian slogans. Thousands of other supporters came out in more overt political rallies. Some sped around scooters honking and again shouting “Shiite, Shiite, Shiite” as they passed anti-government protesters.

“The more Hezbollah attacks them using these sectarian tactics, the more Hezbollah is exposed, and the more Hezbollah will lose,” said Hage Ali, adding that part of the strategy of the counter-revolution is turning it into a sectarian conflict.

If Nasrallah or other Hezbollah or Amal leaders thought a gentle show of force would scare protesters off the street and restore calm, it may have been dangerous miscalculation.

On Monday night, things escalated further with gunfire and clashes, this time with supporters of the Future Movement of the Sunni caretaker Prime Minister Saad Hariri. In the southern city of Tyre, party supporters attacked and burned down a protest camp. Attacks and clashes continued Tuesday.

Many of the anti-government protesters call the party-supporting counterprotesters “brainwashed”—referring not just to Hezbollah and Amal supporters but also to those who have come out in less confrontational shows of support for the country’s president, Michel Aoun, and other parties in recent weeks.

Another protester, Yahya’s friend Nader Issrawi, said he believes that in the end, they all want the same thing.

“What they want is like what we want,” Issrawi said. “We are living a life that is such a shit. We all just want to live in freedom, to eat and build our future.”

But it seems they see different paths to that goal. Issrawi and Yahya were home when the clashes started late Sunday night. “I called him and said, ‘Baha, let’s get to the [street]. Our revolution is in danger,’” Issrawi recalled.

Like many here, Yahya is becoming fearful about where the unrest is heading but says he agrees with Issrawi and that it’s a matter of changing the minds of those standing on the other side of the road. “One day,” Yahya said, “everyone will be convinced.”

*Rebecca Collard is a broadcast journalist and writer covering the Middle East.

Lebanese teachers bring the revolution to class

Nessryn Khalaf/Annahar/November 29/2019

Students believe that the process of learning is enhanced when they can apply theories to realistic scenarios like protest sites.

BEIRUT: Students and teachers were among the first groups to join the Lebanese protests when the revolution erupted and the uproar of dissent became thunderous, and now that classes have resumed, many educators are incorporating the events of the demonstrations into their academic syllabi to express their support.The purpose of this academic shift is to help students gain a deeper understanding of Lebanon’s current political ambiance while supporting their desire to keep attending the demonstrations.

“I always allow my students to voice their opinions as I guide them to do so constructively. I want them to not necessarily accept what others say, but definitely respect it,” expressed Nabilah Haraty, assistant professor of oral communication and English at the Lebanese American University.

She also added that each of her sessions starts with 10-15 minutes of discussion so that her students can share their feelings and points of view in a judgment-free environment.

Shireen Kasamani, one of Haraty’s students, told Annahar: “I admire my professor because she’s been very supportive of students who are protesting. She even asked what we desire to see as an outcome of this revolution and has allowed us to base our speeches on the events observed on the Lebanese streets.”

Rana Younis, another student, highlighted how her ethics professor stopped using the book and instead asked his students to present a research paper describing how different ethical approaches would be used to evaluate the revolution.

Students believe that the process of learning is enhanced when they can apply theories to realistic scenarios like protest sites. This initiative has allowed them to turn the protests into their libraries where knowledge and activism meet.

A literature professor at the American University of Beirut also decided to alter the course syllabus to include some classic political novels like George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

“I want my students to understand that literature is not about reading boring books; it’s rather a manifestation of events observed in their daily lives, and what could be better than dystopian novels to make them comprehend their country’s political turmoil?” the professor said.

Zeinab Ibrahim, an AUB student, said that “the changes made by some professors have enabled the students to keep protesting without worrying about dense course material and accumulating assignments.”

She then explained to Annahar that by being able to link a course’s content to the events of the revolution, she has become more engrossed in the lessons and more inquisitive as both a student and an activist.

*Laura-Joy Boulos, a psychology professor at USJ, mentioned that she has engaged in several classroom discussions with her students to examine the protests and their psychological effects on individuals, for it’s essential to understand how intense emotions like fear, uncertainty, and hope can impact the human

هالة القدسية سقطت».. فورين بوليسي: هكذا خسر «حزب الله» الكثير من رصيده في الشارع اللبناني

فورين بوليسي/29 تشرين الثاني/2019

منذ شهرين مضيا أو ما يزيد، كان لا يُتصوَر أن يخطر هذا النوع من الهتافات أبداً على بال أي شخص في لبنان. لكن في صباح الإثنين، 25 نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني، علا صوت البعض من مئات المحتجين ضد الحكومة، الذين احتشدوا في شارع رئيسي في العاصمة بيروت، قائلين: «إرهابي.. إرهابي.. حزب الله إرهابي»، في مواجهة مشحونة مع مؤيدي حزب الله و «حركة أمل». وأخبر محتجون آخرون أصحاب الهتافات بالتوقف، لكن مع اتساع دائرة السخط من الأوضاع الاقتصادية واجتياح الغضب شوارع لبنان، واستمرار زعيم حزب الله، حسن نصرالله في الدفاع عن الحكومة، بات من الواضح أنَّ هالة القدسية المحيطة بسمعة حزب الله آخذة في التلاشي، كما تقول مجلة Foreign Policy الأمريكية.

«حزب الله جزء من الأزمة في لبنان»

وفي هذا السياق، قال مهند الحاج علي، الباحث في مركز كارنيغي لدراسات الشرق الأوسط للمجلة الأمريكية: «حزب الله يُرى أنه جزء لا يتجزأ من العقبة الأساسية أمام التغيير في لبنان». وغلب على المظاهرات اللبنانية طابعٌ سلمي، ووقوفها بمفردها في مواجهة الطبقة الحاكمة بأكملها بجميع أحزابها وأطيافها. وحتى وقت قريب، كان نصرالله، الذي لا يشغل منصباً رسمياً في الدولة، يُرى على أنه بعيد عن الفساد المستشري في الدولة الذي دفعها نحو الانهيار، وتحديداً وسط قاعدة دعم حزب الله الشيعية، التي اكتسبها من نجاحه في طرد القوات الإسرائيلية من الأراضي اللبنانية المحتلة في عام 2000 بين اللبنانيين من جميع الانتماءات السياسية والطائفية. وحتى عقب حرب 2006، التي ألحقت الدمار بمساحات شاسعة من لبنان، حشدت الجماعة دعماً جماهيرياً لما اعتبره الكثيرون انتصار حماة الدولة على العدوان الإسرائيلي. وفي مايو/أيار 2008، سيطر مقاتلو حزب الله على وسط بيروت بعد أن هددت الحكومة بوقف شبكة اتصالات الجماعة، وإقالة حليفها المسؤول عن أمن المطارات، ولأول مرة حينها صوبت الجماعة أسلحتها نحو الداخل وليس عبر الحدود.

التدخل في سوريا.. محطة مفصلية

وفي الوقت الذي أرسل فيه حزب الله الآلاف من عناصره عبر الحدود للقتال في سوريا لدعم بشار الأسد في عام 2013، بدأ المزيد من الناس يتساءلون عمّن يدافع حزب الله بالضبط. إضافة إلى ذلك، لَحِق مزيدٌ من الضرر بسمعة الجماعة منذ الأيام الأولى للاحتجاجات في منتصف شهر أكتوبر/تشرين الأول، التي شهدت خروج حشود هائلة إلى الشوارع في مناطق تمركز الشيعة، مثل مدينتي صور والنبطية. وفجأة، وبينما يردد المتظاهرون هناك شعارات مناهضة للحكومة على غرار محتجي بيروت -الذين يريدون رحيل جميع القادة السياسيين الطائفيين الحاليين وإجراء انتخابات جديدة في ظل نظام جديد- وجد حزب الله نفسه جزءاً من المؤسسة المُستهدفة. وقال الحاج علي إنَّ الاحتجاجات شكَّلت تحدياً مباشراً للمكاسب التي حققها حزب الله في انتخابات 2018 وتهديداً لأجندة السياسة الخارجية للتنظيم. وخلال الأسبوع الجاري، وفي مواجهة فرقتين كبيرتين من الجيش اللبناني وقوات مكافحة الشغب الشرطية على أرصفة تتناثر عليها الحجارة والعُصي، اشتكى بعض المتظاهرين أنَّ أجندة حزب الله لا تتعلق في الحقيقة ببناء لبنان، بل تمتد إلى دمشق وبغداد وصولاً إلى طهران. وعلى غرار بعض الاحتجاجات المشتعلة في الدولة المجاورة العراق، يصر المتظاهرون الشباب على التنديد بالنفوذ الإيراني على لبنان. إذ هتف بعضهم يوم الإثنين، 25 نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني: «هذا لبنان وليس إيران».

«هذا لبنان، وليس إيران»

حين أصر نصرالله على ألا تتنحى الحكومة اللبنانية، خلال بداية انطلاق المظاهرات في أكتوبر/تشرين الأول، شعر كثيرٌ من المحتجين أنه جزء من المشكلة. وقال الحاج علي: «لقد كانت إحدى تلك اللحظات التي (يصدمك فيها الواقع)؛ إذ شكَّل انضمام الشيعة اللبنانيين إلى حركة الاحتجاج صدمة؛ فلماذا يدافع حزب الله عن الوضع الراهن الذي يشوبه فساد شديد، ويدفع البلاد نحو أزمة مالية واقتصادية؟». وحاول نصرالله تشويه سمعة المحتجين، مشيراً إلى أنهم مموَّلون من حكومات أجنبية. وهي الاتهامات التي قابلها المحتجون بسخرية، بل واستقال العديد من الصحفيين من صحيفة «الأخبار»، التي تؤيد عادةً موقف حزب الله. وقال أحد المتظاهرين، ويُدعى بهاء يحيى، بينما كان ينتظر على طريق جانبي إلى أن يتبدد سيل الغاز المسيل للدموع الذي أطلقه الجيش: «هم يحاولون فقط الحفاظ على النظام. وكل ما نريده هو إزالة النظام. هذه هي حقيقة ما يحدث». في الماضي، نجح حزب الله في تجنب معظم الانتقادات المباشرة حول علاقاته بإيران وسوريا. وعلى مدار عقود من الزمن، تمتع أمراء الحرب في لبنان، وكانوا حينها من النخبة السياسية، بدعم من القوى الإقليمية والدولية، وقد هاجم المتظاهرون هذا التدخل الأجنبي في بلادهم. لكن المحتجين حرصوا على عدم الإشارة لجماعة بعينها، وحتى وقت قريب نَدَر ذكر أسلحة حزب الله التي زودته إيران بها، والتي تفوقت على أسلحة الجيش الوطني للبلاد، ومن المفارقة أنه يتصدى الآن لمؤيدي حزب الله.

أنصار حزب الله يقاومون الاحتجاجات

خلال الأسبوع الماضي، عندما خرج الآلاف من الناس إلى شوارع إيران احتجاجاً على ارتفاع أسعار الوقود هناك، وجد المتظاهرون في وسط بيروت سبباً مشتركاً معهم، وهم يهتفون: «من طهران إلى بيروت.. ثورة واحدة لن تموت». لكن أنصار حزب الله يقاومون؛ إذ رفعت الاحتجاجات المضادة أعلام حزب الله وحركة أمل هذا الأسبوع، ورددت شعارات طائفية مثل «شيعة.. شيعة.. شيعة»، وأكدوا ولاءهم لنصر الله ونبيه بري، زعيم حركة أمل ورئيس البرلمان اللبناني. وفي المقابل، ردَّ المحتجون المعارضون للحكومة بهتافات «الشعب واحد»، ثم علت أصواتهم بغناء النشيد الوطني. وليس واضحاً تماماً كيف اندلعت المواجهة ليل الأحد، 24 نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني، لكن ما هو واضح هو أنها أثارت مخاوف من تصعيد عنيف لتمرد لبنان المستمر منذ ستة أسابيع ضد الحكم الطائفي الرديء، وأضافت «وصمة عار» أخرى إلى صورة حزب الله بأنه المدافع عن البلاد. كان هذا الطريق نفسه هو الجبهة الأمامية لمعظم الحرب الأهلية في لبنان. والجميع هنا يعلم هذا، لكن معظم المحتجين أصغر من أن يتذكروا القناصة ونقاط التفتيش التي سيطرت على الشارع. وتمكن بعض من أنصار حزب الله وحركة أمل من اختراق هذه الجبهة، ومهاجمة المتظاهرين ومطاردتهم إلى الشوارع الجانبية، حيث المباني لا تزال تحمل آثار معارك الحرب الأهلية.

«يريدون تخويفنا»

وقال يحيى، بينما يقف في الطريق الجانبي: «يمكنهم (داعمو حزب الله وحركة أمل) الوصول إلينا إذا أرادوا، لكنهم لا يرغبون في ذلك. هم فقط يريدون إخافتنا». وعاد معظم المتظاهرين الذكور للشارع مرة أخرى حاملين أغصان الأشجار والعُصي. وحاول الجانبان التراشق بالحجارة عبر المنطقة المحرمة التي حددتها صفوف قوات الأمن. وألقى حزب الله باللوم في حادث سيارة وقع في ساعة مبكرة من صباح الإثنين الماضي على الحواجز التي شيَّدها المتظاهرون. ويظهر في شريط فيديو للحادث، سيارة تضرب عقبة في وسط طريق يبدو فارغاً، ولم يظهر فيه أي محتج في الأفق. واعتبر البعض أنها محاولة لتصوير الاحتجاجات على أنها تهديد أمني. وشارك المئات مساء ذلك اليوم في وقفة احتجاجية، ورفعوا أعلام حزب الله وأمل وهم يهتفون بشعارات حزبية وطائفية. فيما خرج آلاف المؤيدين الآخرين في مسيرات سياسية أكثر صراحة؛ إذ جال بعضهم الشوارع بدراجات بخارية وهم يطلقون أبواقها ويهتفون «شيعة.. شيعة.. شيعة» أثناء مرورهم أمام المتظاهرين المناهضين للحكومة. وقال حاج علي: «كلما هاجمهم حزب الله باستخدام هذه التكتيكات الطائفية، ينفضح أكثر، ويخسر المزيد»، مضيفاً أنَّ جزءاً من استراتيجية الثورة المضادة هو تحويل الاحتجاجات إلى صراع طائفي. وإذا ظن نصرالله أو غيره من قادة حزب الله أو حركة أمل أنَّ استعراضاً بسيطاً للقوة سيخيف المحتجين ويبعدهم عن شوارع لبنان ويعيد الهدوء إليها، فهذا سوء تقدير خطير.

«ثورتنا في خطر»

ومساء الإثنين، تصاعدت وتيرة الاحتجاجات بإطلاق نيران واندلاع اشتباكات، لكن هذه المرة مع أنصار «تيار المستقبل» لرئيس حكومة تصريف الأعمال السُني سعد الحريري. ففي مدينة صور الجنوبية، هاجم أنصار الحزب خيمة للمحتجين وأحرقوها. واستمرت الهجمات والاشتباكات حتى يوم الثلاثاء، 26 نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني. ويصف العديد من المتظاهرين المناهضين للحكومة منظمي الاحتجاجات المضادة بأنهم «تعرضوا لغسيل دماغ»، مشيرين ليس فقط لمؤيدي حزب الله وحركة أمل، بل أيضاً لكل الذين خرجوا في استعراض أقل صدامية للتعبير عن دعمهم لرئيس البلاد ميشال عون، وأحزاب أخرى في الأسابيع الماضية. من جانبه، أعرب متظاهر آخر صديق ليحيى، يُدعَى نادر يسراوي، عن اعتقاده بأنه في نهاية المطاف جميع اللبنانيين يريدون نفس الشيء. وقال يسراوي: «ما يريدونه هو نفسه ما نريده. نحن نعيش في ظروف متردية. وما نريده جميعنا هو أن ننعم بالحرية وأن نأكل ونؤسس لمستقبلنا».

لكن يبدو أنَّ كل فريق يرى سبيلاً مختلفاً لتحقيق هذا الهدف. وكان يسراوي ويحيى في المنزل عندما بدأت الاشتباكات في وقت متأخر من ليل الأحد. ويسترجع يسراوي ما حدث قائلاً: «اتصلت به وقلت: بهاء، دعنا نذهب إلى [الشارع]. ثورتنا في خطر». وعلى غرار الكثير هنا، بدأ الخوف ينمو بداخل يحيى حول تطور الاضطرابات، لكنه يقول إنه يتفق مع يسراوي في أنَّ الأمر يتعلق بتغيير عقول أولئك الذين يقفون على الجانب الآخر من الطريق، وقال يحيى: «يوماً ما، سيقتنع الجميع».