Provinces Lead the Center in Iran’s Protests/بريندا شيفر: المحافظات تقود الوسط في احتجاجات إيران

Brenda Shaffer/The Washington Institute/January 05/2018

As ethnic minorities and poverty-stricken provincial communities assume a greater role in nationwide unrest, the regime will likely try to pit them against each other.

The recent antiregime protests in Iran emerged in the country’s peripheral provinces, which is also where the majority of reported deaths have taken place. The momentum of the demonstrations remains strongest in the border provinces rather than Tehran, especially in the northwest and southwest. The outbreak of protests in widespread locations—including rural areas and outside major cities—suggests that the regime will be much more challenged by this movement than the 2009 Green Revolution, which was centered in Tehran and had a clearly identified leadership that could be directly subdued.

Moreover, the current protests include an ethnic element that was absent from the 2009 uprising and could create extra problems for the regime. Although this factor is but one of many grievances galvanizing the demonstrators, the intensity of protests in the border provinces indicate that it might cause serious ethnic unrest. Minority grievances are amplifying economic grievances, which are worse in the provinces than in the Persian heartland. In social media footage reportedly drawn from many demonstrations, participants are using minority languages such as Kurdish and Azerbaijani to voice slogans of ethnic pride. Accordingly, foreign observers should pay more attention to the ethnic factor as they attempt to project future developments in Iran and gauge the regime’s stability.

PROVINCIAL STRUCTURE AND ETHNIC COMPOSITION

Iran is composed of thirty-one provinces (ostan), each with a governor appointed by the central government. In many cases these officials are not natives of the regions they oversee and do not speak the local language. A third of the provinces border at least one foreign country, and most of their residents share ethnic and often family ties with these states. In some provinces, direct trade with neighboring countries competes with or even surpasses trade with Iran’s center.

The majority population of most border provinces is non-Persian, while Iran’s heartland is primarily Persian (though about half the population of Tehran itself consists of minorities). In all, ethnic minorities comprise more than half of the country’s total population of 82 million, according to mainstream academic assessments. The largest group is Azerbaijanis (approximately 24 million), followed by Kurds (8 million), Lurs (3 million), Arabs (3 million), Turkmens (3 million), and Baluch (3 million).

ETHNIC AND PROVINCIAL GRIEVANCES

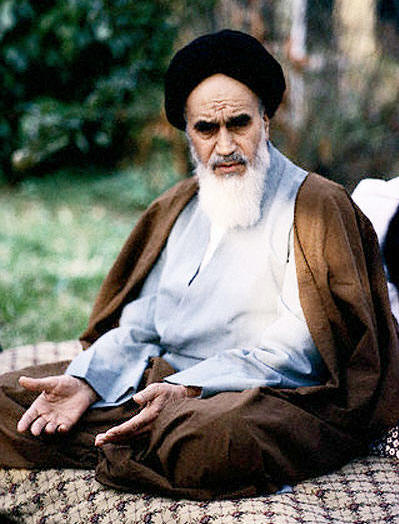

Ethnic identity can take on a wide range of roles in Iran. Many minority citizens identify completely as Iranian, and their ethnic identity has little political significance. In fact, some of the regime’s most important pillars hail from minority communities, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei himself, who is Azerbaijani. For many others, however, ethnic identity is primary, and their feelings of separation may be fueled by a host of regime policies that affect their communities at home and abroad, and by state media outlets that regularly mock minorities.

Regarding the current unrest, several signs indicate that ethnicity has become an important driver. For one, the protests first emerged in the city of Mashhad, which has a large Turkmen population and is located two hours’ drive from the border with Turkmenistan. From there, the protests spread to many small towns in the north and southwest, mostly in Kurdish and Arab areas. Only on the third day did significant protests begin in Tehran, and many demonstrations in the heartland erupted in communities populated by minorities (e.g., the Azerbaijani-dominated town of Karaj outside the capital).

In addition, dozens of social media posts have shown protestors in certain provinces blaring ethno-nationalist demands and music while chanting slogans in minority languages such as Azerbaijani, Kurdish, and Arabic. A number of foreign organizations that advocate for the rights of ethnic minorities have issued statements in support of the protests, but it is not clear how representative they are of people on the ground. Whatever the case, ethnic demands seem to be a powerful mobilizer for wide segments of the population who may not be politically active.

The provinces also face more economic hardship than the heartland. Income levels and social services in the periphery are lower, unemployment rates are higher, and many residents suffer from extensive health and livelihood challenges emanating from ecological damage. Whether justified or not, provincial communities often blame this damage on central government policies.

Furthermore, the regime does not allow ethnic minorities to use their native languages in official settings such as courts and schools, in violation of constitutional protections. Perhaps as a result of this, many minority citizens in large cities report that Persian is their stronger functional language.

The current protests are not the first sign of opposition in the border provinces. Ethnic minority operatives have carried out a number of domestic terrorist operations in recent months, including the Kurdish attacks on the parliament building and Khomeini Mausoleum in Tehran last June, as well as frequent attacks against border guards in the northwest.

Meanwhile, the number of judicial executions carried out in Kurdish and Baluch areas is far above the average seen in Iran’s center. While the regime claims that these executions are for crimes such as drug smuggling, their disproportionate frequency suggests that authorities may be using them to quash opposition activity. In addition, the head of a major diaspora organization that advocates for the rights of Arabs in Iran was assassinated last November as he was leaving his home in the Netherlands. Tehran has not claimed responsibility, and there is no hard evidence of its involvement, but no other likely suspects exist.

Iran’s foreign policy toward its neighbors also has domestic implications. For example, the regime’s efforts to punish the Kurdish independence movement in Iraq last fall created indignation among Iranian Kurds. In addition, larger numbers of Iranian Azerbaijanis have taken chartered tourism trips to the neighboring Republic of Azerbaijan over the past year, and some may have been influenced by the experience of enjoying their native language and culture free of the restrictions imposed in Iran.

HOW WILL THE REGIME RESPOND?

The regime’s usual playbook for dealing with ethnic and provincial opposition is to blame foreigners for its emergence while attempting to pit domestic groups against each other. Khamenei has already blamed the current protests on foreign enemies. In reality, however, the unrest in Iran’s provinces is clearly homegrown.

Fomenting conflict between domestic communities has worked very well for the regime in the past, so Tehran may now try to exacerbate Kurdish-Azerbaijani tensions—especially in West Azerbaijan province, where these two groups cohabitate and have grievances against each other. The regime can also appeal to Iranian nationalist sentiments among the economic and political elite. This includes opposition elites—when faced with potential ethnic conflict in the past, many such figures have been unwilling to risk their control over the provinces or the dominance of the Persian language for the sake of addressing minority issues or achieving democratic reform.

As for the prospect of international action, the West has often supported peoples’ right to protest peacefully in various countries—the challenge is how to make such support effective. On January 2, U.S. ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley made clear that Washington is pushing the Security Council to discuss potential responses to the Iran situation. Another way to support the people is through international broadcasting that gives them reliable information about what is happening in their country, counterbalancing the censorship and misinformation seen in regime news outlets. Thus far, Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty have not been very effective on that front, especially in broadcasting aimed at Iran in languages other than Persian. Given the seemingly strong ethnic drivers in the latest unrest, both outlets should consider boosting their programming in minority languages.

**Prof. Brenda Shaffer is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Eurasian, Russian, and East European Studies, and author of the book Borders and Brethren: Iran and the Challenge of Azerbaijani Identity (MIT Press, 2002).

المحافظات تقود الوسط في احتجاجات إيران

بريندا شيفر/معهد واشنطن/4 كانون الثاني/يناير 2018

اندلعت شرارة التظاهرات الأخيرة المناهضة للنظام في إيران في المحافظات الطرفية للبلاد، التي كانت بدورها مسرحاً لغالبية حالات الوفاة المعلنة. ولا يزال زخم التظاهرات على أشده في المحافظات الحدودية وليس في طهران، لا سيما في الشمال الغربي والجنوب الغربي من البلاد. ويشير اندلاع التظاهرات الواسعة الانتشار في أماكن مختلفة من البلاد – بما فيها المناطق الريفية وخارج المدن الكبرى – إلى أن هذا الحراك سيضع النظام أمام تحديات أكبر بكثير من تلك التي طرحتها احتجاجات “الحركة الخضراء” عام 2009، والتي تركّزت في طهران وتمتعت بقيادة واضحة يمكن كبتها وإخضاعها مباشرة.

وعلاوةً على ذلك، تشمل الاحتجاجات الحالية عنصراً عرقياً كان غائباً خلال انتفاضة عام 2009 ومن شأنه أن يسبب مشاكل إضافية للنظام. وعلى الرغم من أن هذا العامل ليس سوى أحد المظالم العديدة التي أججت حماسة المتظاهرين، إلّا أنّ حدة الاحتجاجات في المحافظات الحدودية تشير إلى أن ما يجري قد يطلق شرارة اضطرابات عرقية خطيرة. وتؤدي مظالم الأقليات إلى تفاقم المظالم الاقتصادية التي هي أكثر حدة في المحافظات من تلك في العمق الفارسي. وقد ظهر في مقاطع فيديو تناقلتها وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي والتي أفادت التقارير أنها مسجلة خلال العديد من التظاهرات، أن المشاركين يستخدمون لغات الأقليات على غرار اللغة الكردية والأذربيجانية ليرددوا شعارات تبجل الفخر العرقي. وانطلاقُا من هذا الواقع، على المراقبين الأجانب إيلاء المزيد من الاهتمام للعامل العرقي عند محاولتهم التنبؤ بالتطورات المستقبلية في إيران وتقييم استقرار النظام وثباته.

هيكلية المحافظات والتركيبة العرقية

تتألف إيران من 31 محافظة (بالفارسية: استان)، لكل منها محافظ تعيّنه الحكومة المركزية. وفي حالات عديدة، لا يكون هؤلاء المسؤولون من أبناء المناطق التي يتولون حكمها كما أنهم لا يتحدثون اللغة المحلية. ويقع ثلث المحافظات عند الحدود مع دولة أجنبية واحدة على الأقل، ويتشارك معظم سكانها الأصول العرقية، وغالباً ما تجمعهم روابط أسرية بهذه الدول. وفي بعض المحافظات، تنافس التعاملات التجارية المباشرة مع الدول المجاورة التجارة مع مركز إيران أو حتى تتخطاها.

إن غالبية سكان معظم المحافظات الحدودية هم من غير الفارسيين، في حين أن وسط إيران فارسي عموماً (على الرغم من أن نصف سكان طهران نفسها مكوّن من أقليات). وفي المجموع، تشكّل الأقليات العرقية أكثر من نصف إجمالي عدد سكان البلاد البالغ 82 مليون نسمة، وفقاً للتقييمات الأكاديمية الرئيسية. وأكبر مجموعة من هذه الأقليات هي تلك المكونة من الأذربيجانيين (حوالي 24 مليون)، تليها الأكراد (8 ملايين)، واللور [أو لُر أو الأكرد الفيلية] (3 ملايين)، والعرب (3 ملايين)، والتركمان (3 ملايين)، والبلوش (3 ملايين).

مظالم الأعراق والمحافظات

يمكن للهوية العرقية أن تضطلع بمجموعة واسعة من الأدوار في إيران. فالعديد من المواطنين المنتمين إلى الأقليات يعرّفون أنفسهم تعريفاً تاماً على أنهم إيرانيون، وأن هويتهم العرقية هي ذات أهمية سياسية ضئيلة. وفي الواقع، تنحدر بعض أهم ركائز النظام من مجتمعات الأقليات بمن فيهم المرشد الأعلى علي خامنئي نفسه، الذي هو من أصول أذربيجانية. غير أنه بالنسبة للكثيرين غيرهم، تُعتبر الهوية العرقية أساسية، وربما تتنامى رغبتهم في الانفصال بسبب مجموعة من سياسات النظام التي تؤثر على مجتمعاتهم على الصعيد المحلي والخارجي، وبسبب وسائل الإعلام الحكومية التي لا تنفك تعامل الأقليات بازدراء.

وفيما يخص الاضطرابات المندلعة حالياً، تدلّ مؤشرات عديدة على أن الانتماء العرقي أصبح عاملاً مهماً. فعلى سبيل المثال، انطلقت الاحتجاجات في الأساس من مدينة مشهد، التي تضمّ شريحة واسعة من التركمان وتقع على بعد ساعتين بالسيارة من الحدود مع تركمانستان. ومن هناك امتدت الاحتجاجات إلى العديد من المدن الصغيرة في الشمال الغربي والجنوب الغربي من البلاد، ومعظمها في المناطق الكردية والعربية. ولم تبدأ الاحتجاجات الكبيرة في طهران إلا في اليوم الثالث، كما اندلعت مظاهرات كثيرة في وسط البلاد في مجتمعات تسكنها الأقليات (مثلاً مدينة كرج التي يهيمن عليها الأذربيجانيون خارج العاصمة).

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن عشرات التعليقات عبر وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي قد أظهرت المحتجين في بعض المحافظات وهم يطلقون مطالب عرقية – قومية مترافقة مع موسيقى في الوقت الذي يرددون فيه شعارات بلغات الأقليات مثل اللغة الأذربيجانية والكردية والعربية. وقد أصدرت عدد من المنظمات الأجنبية التي تنادي بحقوق الأقليات العرقية تصريحات مؤيدة للاحتجاجات، ولكن ليس من الواضح إلى أي مدى تمثل هذه المنظمات المواطنين فعلياً على الأرض. ومهما كانت الحالة، يبدو أن مطالب [الجماعات] العرقية تمثّل محركاً قوياً لشرائح واسعة من السكان التي قد لا تكون ناشطة سياسياً.

كما تواجه المحافظات صعوبات اقتصادية أكثر من تلك في وسط البلاد. فمعدلات الدخل والخدمات الاجتماعية في المناطق المحيطة هي في مستويات أدنى، ومعدلات البطالة في مستويات أعلى، ويعاني العديد من السكان تحديات صحية ومعيشية باهظة ناجمة عن الأضرار البيئية. وسواء كان هناك ما يبرر ذلك أم لا، غالباً ما تحمّل مجتمعات المحافظات مسؤولية هذا الضرر على سياسات الحكومة المركزية.

فضلاً عن ذلك، لا يسمح النظام للأقليات العرقية باستخدام لغاتهم الأصلية في الأماكن الرسمية مثل المحاكم والمدارس، في انتهاك للحماية الدستورية. وربما نتيجةً لذلك، يقول العديد من مواطني الأقليات في المدن الكبرى إن الفارسية هي لغتهم الوظيفية الأقوى.

يُذكر أن الاحتجاجات الحالية ليست الإشارة الأولى إلى المعارضة في المحافظات الحدودية. فقد نَفذت عناصر من الاقليات العرقية عدداً من العمليات الإرهابية المحلية خلال الأشهر القليلة الماضية، بما فيها الهجمات الكردية على مبنى البرلمان وضريح الخميني في طهران خلال حزيران/يونيو الماضي، فضلاً عن الهجمات المتكررة ضد حرس الحدود في الشمال الغربي.

وفي غضون ذلك، يتجاوز عدد الإعدامات القضائية التي نُفذت في المناطق الكردية والبلوشستانية إلى حدّ كبير المتوسط الذين يشهده وسط إيران. وبينما يدّعي النظام أن هذه الإعدامات تتعلق بجرائم مثل تهريب المخدرات، إلّا أنّ وتيرتها غير المتناسبة تشير إلى أن السلطات ربما تلجأ إليها من أجل قمع نشاط المعارضة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، اغتيل رئيس منظمة شتات كبرى تدافع عن حقوق العرب في إيران في تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر الماضي، بينما كان يغادر منزله في هولندا. ولم تتبنَ طهران المسؤولية عن تلك العملية، ولا يوجد دليل دامغ على تورطها فيها، ولكن ليس هناك أي مشتبه بهم آخرين.

كما هناك تداعيات محلية لسياسة إيران الخارجية تجاه الدول المجاورة. فعلى سبيل المثال، أدّت مساعي النظام لمعاقبة حركة الاستقلال الكردية في العراق في الخريف الماضي إلى إثارة السخط والاستياء في أوساط الأكراد الإيرانيين. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قامتعاد أعداد أكبر من الأذربيجانيين الإيرانيين برحلات سياحية مستأجرة إلى جمهورية أذربيجان المجاورة خلال العام الماضي، وقد يكون بعضهم قد تأثر بتجربة الاستمتاع بلغتهم وثقافتهم الأم بعيداً عن القيود المفروضة عليهم في إيران.

كيف سيرد النظام؟

تتمثل قواعد اللعبة الاعتيادية التي يمارسها النظام للتعامل مع المعارضة العرقية وفي المحافظات في تحميل الأجانب مسؤولية بروزها في الوقت الذي يسعى فيه إلى تحريض المجموعات المحلية ضدّ بعضها البعض. وقد سبق أن ألقى خامنئي اللوم على الأعداء الخارجيين في اندلاع الاحتجاجات الحالية. غير أنه في الحقيقة، يبدو جلياً أن الاضطرابات في المحافظات الإيرانية ناشئة من الداخل.

وكانت إثارة النزاع بين المجتمعات المحلية قد عادت بفائدة كبيرة على النظام الإيراني في الماضي، لذلك قد تحاول طهران الآن مفاقمة التوترات الكردية – الأذربيجانية – لا سيما في محافظة أذربيجان الغربية حيث تعيش هاتان المجموعتان معاً ولديهما شكاوى ضدّ بعضهما البعض. كما يمكن للنظام استمالة المشاعر القومية الإيرانية في أوساط النخبة الاقتصادية والسياسية. ويشمل ذلك نخب المعارضة – التي عندما واجهت احتمال اندلاع نزاع عرقي في الماضي، لم تكن العديد من هذه الشخصيات مستعدة للمخاطرة بسيطرتها على المحافظات أو هيمنة اللغة الفارسية لصالح معالجة مشاكل الأقليات أو تحقيق الإصلاح الديمقراطي.

أما بالنسبة لآفاق التحرك الدولي، فلطالما دعم الغرب حق الشعوب في التظاهر بشكل سلمي في بلدان مختلفة – ويكمن التحدي في كيفية جعل هذا الدعم فعالاً. وفي الثاني من كانون الثاني/يناير، أوضحت سفيرة الولايات المتحدة لدى الأمم المتحدة نيكي هالي أن واشنطن تحض مجلس الأمن الدولي على مناقشة الردود المحتملة إزاء الوضع في إيران. وتتمثل طريقة أخرى لدعم الشعب الإيراني في البث الدولي الذي يمنحهم معلومات موثوقة عما يجري في بلدهم، لموازنة الرقابة والتضليل في المحطات الإخبارية التابعة للنظام. وحتى الآن، لم تكن أي من “صوت أمريكا” و”إذاعة أوروبا الحرة”/”راديو ليبرتي” فعالة بشكل كبير في هذا الصدد، وخاصةٍ في بث أخبار تستهدف إيران بلغات غير الفارسية. ونظراً إلى المحفزات العرقية القوية على ما يبدو خلال الاضطرابات الأخيرة، يجب أن تدرس هاتان المحطتان زيادة برامجهما بلغات الأقليات.

البروفيسور بريندا شيفر هي زميلة أقدم في “مركز الطاقة العالمي” التابع لـ “المجلس الأطلسي”، وأستاذة مساعدة في “مركز الدراسات الأوروبية الأوراسية والروسية وأوروبا الشرقية” في “جامعة جورج تاون”، ومؤلفة كتاب “الحدود والإخوة: إيران وتحدّي الهوية الأذربيجانية” ( “إم آي تي بريس”، 2002).