Nasser’s populist rhetoric still affects region

Dr. Simon Waldman/The National/June 05/17

Everywhere you look, populism is on the rise. In the UK, there’s Brexit; in the United States, there’s Donald J Trump; in Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan keeps winning elections.

The Australian academic Benjamin Moffitt explains that populism is a political style, a kind of repertoire, a performance if you will. Indeed, one could certainly add that it’s a form of political theatre where social media is the stage and soundbites within 140 characters are the actors’ lines. The populist leader likes to simplify policy and groups political life into “us” and “them” with appeals to “the people” against a particular group, nation or outsider.

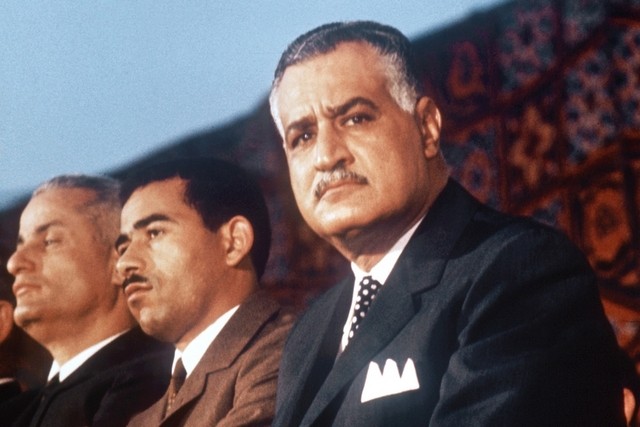

Such displays of a political performance are not new. There are plenty of past examples. But, it was in the Middle East that the populist leader par excellence emerged. His name was Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Rising through the ranks of the military during turbulent 1930s and 1940s Egypt, Nasser was aware of the widespread anti-British sentiment across the country. Confined to the barracks, Nasser established the Free Officer movement. He used the loss of Palestine to the nascent state of Israel during the 1948 war to rally more officers to his cause, blaming the British-backed King Farouk for giving Egyptian troops defective weaponry.

The Free Officers staged a coup in July 1952. First it was General Naguib who claimed leadership. But with the support of the Liberation Rally, an organisation formed by Nasser to create the appearance of popular street support, not unlike fake Twitter and Facebook accounts used by some political campaigns today, Nasser took over as president in 1954, a position he held until his death in 1970.

Nasser used the social media of his day, the radio station Voice of the Arabs, to spread his message across the Arab world. Using colloquial language, he styled himself a man of the people standing up to imperial powers while promoting Arab unity and decrying “reactionary” Arab regimes. Meanwhile, in Egypt, Nasser initiated land reforms and other popular domestic policies. Although they did little to change inequality, they helped his claim to represent the ordinary man.

Nasser’s popularity reached unprecedented heights after he nationalised the Suez Canal in 1956. It was an act of defiance against the colonial powers of Britain and France and a means to fund the Aswan Dam, a huge project Nasser said was for the benefit of the common Egyptian. London and Paris conspired to depose Nasser: Israel would attack Egypt, prompting Britain and France to intervene and remove him. But Nasser was defiant and held his ground against Britain, France and Israel, who bungled their operation.

Nasser’s popularity was now so great that it was by the invitation of Syria’s nationalists that, in 1958, the United Arab Republic was formed, unifying Egypt and Syria and making Pan-Arabism appear a reality and not just a dream.

But Nasser’s undoing was his disastrous attempt to lead the Arab world to liberate Palestine in 1967.

Perhaps this was a bid to rekindle his light which was waning after Syria left the UAR in 1961, complaining of Egyptian colonialisation of all things. Perhaps Nasser wanted to reverse Egypt’s losses following its intervention in the Yemen civil war to support the republicans against Saudi-backed royalists. The long and bloody war became known as Egypt’s Vietnam. Or perhaps Nasser was disturbed by accusations that he was doing nothing to support Jordan or Syria in military skirmishes and conflagrations with Israel. “Nasser is hiding behind the skirts of the UN,” quipped King Hussein of Jordan, referring to the UN forces stationed in the Sinai separating Israeli and Egyptian troops.

Nasser expelled the UN forces from Sinai, closed the straights of Tiran to Israeli shipping and, to the cheers of the masses, proclaimed his intention to destroy Israel. On June 5, 1967, Israel launched a pre-emptive strike. After six days of fighting, Egypt lost Sinai while Israel controlled the West Bank, Golan Heights and East Jerusalem, which it has held on to ever since. Nasser accused Britain and the US of colluding with the Israelis. But he had been defeated.

Nasser resigned. In one last populist performance, crowds gathered in a stage-managed call from the street for he to remain president. he died three years later. His goals of defeating Israel and seeing through pan-Arab unity lay in tatters.

As the fate of Nasser shows, without substance populists are merely performers facing a possible final curtain call of failure.