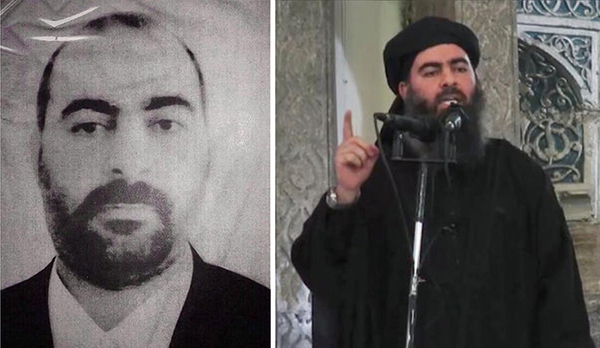

Analysis: ISIS leader al-Baghdadi is living on borrowed time

Yossi Melman/Jerusalem Post/June 17/16

Information released Wednesday on the demise of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the founder of ISIS, was premature, and not for the first time. In the past year, there have been at least three false reports that al-Baghdadi was killed during US airstrikes. Every hour that al-Baghdadi continues to live, he is essentially part of “the walking dead.” Sooner or later intelligence will lead to a successful attack by an American drone or plane and the operational cycle will be closed. Al-Baghdadi is living on borrowed time. He knows it, as do his senior commanders, who in the past weeks have been on the defensive, losing outposts, villages, cities and territories. The Caliphate understands that its territorial control is ending. The Iraqi army, along with Shi’a militias under the guidance of Iranian al-Quds force commander, General Qassam Sulimani, are besieging the city of Fallujah in Iraq and it’s just a matter of time until it falls. The Syrian army from the West is closing in on the city of Raqqa, capital of the Caliphate, and Kurdish forces are advancing from the North. As ISIS control lessens, the despair and urge to commit terror attacks is strengthened: to explode car bombs in Damascus and Baghdad, to enhance their influence and induction of young radical Muslims in the West. Sooner or later ISIS will go back to being what it was when it began: a terror organization that is an off-shoot of al-Qaida that operates as a murder machine more dangerous than the original ever was. With all the differences between them, the two attacks this past week – Orlando and Paris – indicate such a direction. The terror attacks of the past few months in Brussels and Paris, along with dozens of other such attacks that defense forces in Western Europe were successful in preventing, all carry the fingerprint of ISIS. It is difficult to pinpoint a common denominator between them all.

In some of the cases, networks of Syrian and Iraqi war ‘veterans’ were organized and directed from Raqqa. In other cases, individuals or couples declared their allegiance to ISIS and al-Baghdadi, as in Orlando, but the real motives were from family/personal distress or religious radicalization and hate for the West. Most of the Western terror attacks in the past few years, especially those in Orlando and Paris, exposed the weak points and loopholes of the intelligence and law enforcement communities. At least some of the terrorists were ‘checked and vetted,’ in other words, known to local police and authorities. Some appeared on lists of known dangerous Islamists, some were even arrested and questioned, yet eventually fell through the cracks in the system. This comes from negligence and from an absence of awareness. Even the world’s best security forces cannot always cover all potential suspects, certainly not without harming important democratic western values, such as human rights, privacy, and due process of the law. Slowly, the West is learning through a difficult path of sacrifices how to fight against murderous Islamic terrorism. Maybe it would be possible to take short cuts if there was a higher awareness and decisiveness, however just as the West succeeded in reducing the danger of al-Qaida and its leader Osama Bin Laden, it will succeed, eventually, in the struggle against ISIS and al-Baghdadi.

However, no one should deceive themselves that the idea itself – Holy Jihad against the Christian West and all infidels – will disappear from the world.

Washington’s War on the Islamic State Is Only Making It Stronger

By Hassan Hassan/Foreign Policy/June 16, 2016

The caliphate is losing territory in Iraq and Syria, but the U.S.-backed military campaign is stoking sectarian tensions that could spread global jihad.

The Islamic State’s international appeal has become untethered from its military performance on the ground. Sunday’s terror attack at a nightclub in Orlando, Florida, which left 49 people dead, could be an example of this growing disconnect.

The rampage, committed by a man who pledged allegiance to Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi before opening fire, came amid near-consensus that the Islamic State is in sharp decline.

For the first time since U.S.-led coalition operations began two years ago, almost all of the group’s vital strongholds in Syria, Iraq, and Libya have come under serious pressure.

For the first time since U.S.-led coalition operations began two years ago, almost all of the group’s vital strongholds in Syria, Iraq, and Libya have come under serious pressure. In a recent statement, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, the group’s spokesman, even alluded to the fact that followers should be prepared for losses, from Sirte to Mosul.

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Erdogan?

Slowly, but inexorably, Turkey is headed off a cliff.

But while the group’s performance has hit an all-time low, its appeal does not seem to have diminished. CIA Director John Brennan recognizes this fact: “Despite all our progress against ISIL on the battlefield … our efforts have not reduced the group’s terrorism capability and global reach,” he told the Senate Intelligence Committee on June 16, using another term for the Islamic State. “[A]s the pressure mounts on ISIL, we judge that it will intensify its global terror campaign to maintain its dominance of the global terrorism agenda.”

Brennan also confirmed that the CIA had found no “direct link” between Omar Mateen, the gunman in Orlando, and the Islamic State. This is no surprise, as Mateen does not seem to fit familiar patterns of dogmatic support for the group. In the space of three years, he had supported Hezbollah, al Qaeda, and the Islamic State. His profile suggests that he belongs in the category of sympathizers who are only superficially influenced by the organization’s ideology, but who nonetheless can be inspired to carry out attacks in its name.

Such sympathizers are not driven by the Islamic State’s military successes, such as the takeover of Mosul in the summer of 2014. The group built its narrative around Sunni victimization, an idea that both predates its establishment of a caliphate and continues to exert a strong pull on many in the Middle East. The Islamic State has also tapped into the rampant political stagnation and popular grievances to gain popular support beyond the number of people who actually joined its ranks.

Consider, for example, the ongoing offensives against the Islamic State in Fallujah, Raqqa, and Manbij. While Washington insists the onslaughts include forces that represent the Sunni Arab communities that dominate the three cities, the prominence of Iranian-backed sectarian militias and Kurdish groups has triggered outrage in groups that are otherwise hostile to the Islamic State.

Two examples stand out. As the People’s Protection Units advanced on Raqqa, the activist group Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently warned that civilians in the city were drifting toward the Islamic State due to their hatred for the Kurdish group. Meanwhile, Arabic media like al-Arabiya and al-Hayat — which last year described the offensive on the Islamic State-held city of Tikrit as a “liberation” — called the war on Fallujah a sectarian conflict, led by Iranian spymaster Qassem Suleimani.

Many observers throughout the region see Washington turning its back on Sunni civilians in order to cozy up to Tehran and Moscow. Reports in Arabic media have accused the United States of deliberately backing a sectarian war against Sunnis. This narrative invokes old patterns that could again help the Islamic State convert territorial losses into legitimacy among certain segments of the Sunni world. Even ideologically confused people like Mateen, who supported the Shiite militant group Hezbollah in 2013, might be led to support the Islamic State even as they do not follow its strict religious ideology.

U.S. officials, however, are publicly making the case that the war against the Islamic State is an unqualified success. In a news briefing two days before the attack in Orlando, Brett McGurk, the presidential special envoy to the anti-Islamic State coalition, pointed to eight indicators to argue that the group was suffering on almost every front, from its fighters’ morale to its sharply reduced finances. He credited the Iraqi government with making impressive strides in dealing with the humanitarian situation in the country, and asserted that the forces leading the attacks in Fallujah and northern Syria are Sunni locals and the Iraqi Army. There had been isolated atrocities committed by militias, he said, but “everybody is saying and doing the right thing to make sure that anyone who commits a human rights violation is held to account.”

This assessment, however, understates the political and social issues that led to the rise of the Islamic State in the first place and overstates factors that played little role in that rise. The Iraqi government today appears even more dominated by sectarian forces than the period before the Islamic State’s capture of Mosul in 2014. The narrative prevalent throughout the region that the continuing battle in Fallujah is a nakedly sectarian war belies McGurk’s hopeful — if not misleading — assessment.

Political grievances are the beating heart of the Islamic State. The way the Fallujah battle has been conducted, regardless of how American officials present it, has caused some Sunnis who would otherwise oppose the Islamic State to see it as the enemy of their enemies. More people, not fewer, might start to see the group as their champion if it is defeated by the wrong forces. Such grievances could not only fuel insurgencies in Syria and Iraq, but also inspire future lone wolves in the United States.

The appeal of the caliphate might similarly survive territorial losses. In his briefing, McGurk pointed to the idea of a caliphate as the key driver of foreign fighter recruitment. “I’ve traveled now all around the world, and the common denominator when I asked leaders in various capitals what is it that’s driving your young people to this movement — the common denominator is this notion of a historic caliphate,” he said. “So we have to shrink the core, and we’re doing that.”

But “shrinking the core” works only if the war effort simultaneously addresses the underlying grievances of communities from which the Islamic State draws support.

But “shrinking the core” works only if the war effort simultaneously addresses the underlying grievances of communities from which the Islamic State draws support. It is imperative to enable Sunni forces to fight and defeat the Islamic State, and thus portray the fight to Muslims across the world as an extremist group slaughtering its fellow Sunnis, and not a sectarian war. However, the bulk of the effort against the Islamic State so far seems to be focused on defeating the organization militarily, while the political, sectarian, and social mess created in the process is left for another day — a classic example of putting the cart before the horse.

The war against the Islamic State is heading in two directions. The group is clearly weakened on the ground, but the nature of the losses it is suffering has strengthened its legitimacy among certain segments of the Sunni world. This is a trend that should be of grave concern to U.S. officials, as the group’s continuing support could lay the groundwork for its eventual resurgence — and more lone wolf attacks like the one in Orlando.

More focus should be given to allowing the political track to catch up to military advances. But as the situation stands today, the military campaign might be creating the circumstances that will enable the group’s appeal to survive its territorial demise.