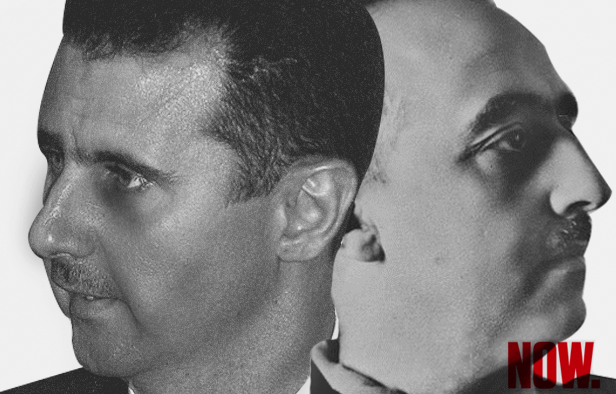

Everybody’s wars: The similarities between Syria and Spain

Micheal Young/Now Lebanon/April 21/16

Paul Preston’s monumental biography of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco provides very useful insights into the Spanish civil war, and by extension into the current war in Syria. It has often been observed that the Syrian conflict, like the one in Spain between 1936 and 1939, began as an internal struggle before expanding into a regional proxy war. Franco, who had been one of the top generals revolting against the Republic, led by President Manuel Azana, was supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, while the Republican side was backed, most prominently, by the Soviet Union.

While the Syrian and Spanish civil wars were different in many regards, the similarities are instructive. For one thing, Franco, like Bashar al-Assad, was not particularly liked by his foreign allies, who nevertheless viewed his triumph as of vital interest to them. Indeed, the war began as Germany and Italy were preparing to expand their power in Europe through war, so a Franco defeat would have represented a major reversal. While Franco could hardly be compared to those who rose up against Assad rule, like them he became highly dependent on outside supporters. Franco, no less than the foes of the Syrian president, showed that uprisings can begin as impulses only partly thought through, requiring rapid outside assistance to stay on track. The Syrians, in contrast to Franco, had to rely on themselves at the start of their rebellion, but as the regime hit back hard, their dependence on regional actors grew.

This soon gave the foreign actors great leverage over the Syrian participants, as it had in Spain. Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler sent their military specialists to assist Franco, just as Vladimir Putin and the Iranian regime have done theirs. With help comes arrogance, and just as the Italians and Germans were soon dismissive of Franco’s plodding tactics, better for a war of attrition, Assad’s allies were soon mocking his army. But at the same time both Assad and Franco showed that there is much strength in weakness. Because the two enjoyed decisive patronage from outside states, their loss simply became unacceptable. Franco’s forces were doubtless stronger for a longer time than were Assad’s, but early on the Spanish general feared that his forces would bog down, and he redoubled his request for military aid from Germany and Italy.

The aid came, just as Russia and Iran made sure that Assad always had what he needed to remain in power. It’s true that Franco was looking to triumph, while Assad has mainly hoped to survive, but for all practical purposes the calculations of the allies were the same: to prevent the defeat of their man.

The Spanish civil war has often been called a prelude to World War II. It’s not clear whether Syria is a prelude to anything, but so destructive has the war been that one can only hope that it will usher in a long period of peace born of fear. In light of this, Spain proved that whoever wins, war is often the anteroom to a long period of retrenchment. An important theme developed by Preston is that Franco, despite Spain’s civil war, would have liked to participate in World War II on the side of the Axis powers.

His ambition was to sit at the table of the victors, or so he thought, and gain territory in North Africa from France. But because the Spain that emerged from the civil war was devastated and its people starving, this proved impossible. When Franco tried to get a German commitment to hand over territory in Morocco, as well as supply him with needed food and weapons, the Germans dithered, leaving the dictator increasingly disillusioned. He and his army soon admitted that Spain was in no real condition to go to war. Ultimately the vulnerabilities of their state served the dual purpose of making the Germans hesitate to commit to Franco so he would enter the war, persuading Franco to maintain Spanish neutrality.

That may not have a great deal to do with Syria today, but it does, perhaps, tell us something about its future. Civil war kills the life of a country, as does dictatorship. So what can it mean when a dictator wins a war against his own people, particularly an exceptionally savage one? Franco surely had his supporters, but he will forever be remembered for the violence he unleashed on his countrymen. When King Juan Carlos took Spain toward democracy in 1976, he was only removing it from the sordid time warp in which Franco had placed . Assad may survive politically, but it’s hard to imagine him ever putting Syria back together again. Like Franco he committed an original sin, and for as long as he’s around he will represent an indelible stain on his country. Few look back with longing on the Spanish caudillo, on that stain in Spain’s modern history. There’s no reason why Assad should fare any better.

**Michael Young is a writer and editor in Beirut. He tweets @BeirutCalling