Sharia Law or One Law for All?

Denis MacEoin/Gatestone Institute/March 12, 2016

Here is the fulcrum around which so much of the problem turns: the belief that Islamic law has every right to be put into practice in non-Muslim countries, and the insistence that a parallel, if unequal, legal system can function alongside civil and criminal law codes adhered to by a majority of a country’s citizens.

Salafism is a form of Islam that insists on the application of whatever was said or done by Muhammad or his companions, brooking no adaptation to changing times, no recognition of democracy or man-made laws.

The greatest expression of this failure to integrate, indeed a determined refusal to do so, may be found in the roughly 750 Muslim-dominated no-go zones in France, which the police, fire brigades, and other representatives of the social order dare not visit for fear of sparking off riots and attacks. Similar zones now exist in other European countries, notably Sweden and Germany. According to the 2011 British census there are over 100 Muslim enclaves in the country.

As millions of Muslims flow into Europe, some from Syria, others from as far away as Afghanistan or sub-Saharan Africa, several countries are already experiencing high levels of social breakdown. Several articles have chronicled the challenges posed in countries such as Sweden and Germany. Such challenges are socio-economic in nature: how to accommodate such a large influx of migrants; the rising costs of providing then with housing, food, and benefits, and the expenses incurred by increased levels of policing in the face of growing lawlessness in some areas. If migrants continue to enter European Union countries at the current rate, these costs are likely to rise steeply; some countries, such as Hungary, have already seen how greatly counterproductive and self-destructive Europe’s reception of almost anyone who reaches its borders has been.

The immediate impact, however, of these new arrivals is not likely to be a simple challenge, something that may be remedied by increasing restrictions on numbers, deportations of illegal migrants, or building fences. During the past several decades, some European countries – notably Britain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark — have received large numbers of Muslim immigrants, most of them through legal channels. According to a Pew report in 2010, there were over 44 million Muslims in Europe overall, a figure expected to rise to over 58 million by 2030.

The migration wave from Muslims countries that began in 2015 is likely to increase these figures by a large margin. In France, citizens of former French colonies in Morocco, Algeria, and some sub-Saharan states, together with migrants from several other Muslim countries in the Middle East and Asia, form a population estimated at several million, but reckoned to be the largest Muslim population in Europe. France is closely followed by Germany – a country now taking in very large numbers of immigrants. There are currently some 5.8 million Muslims in Germany, but this figure is widely expected to rise exponentially over the next five years or more.

The United Kingdom, at around 3 million, has the third largest Muslim population in Europe. Islam today is the second-largest religion in the country. The majority of British Muslims originally came from rural areas in Pakistan (such as Mirpur and Bangladesh’s Sylhet), starting in the 1950s. Over time, many British Muslims have integrated well into the wider population. But in general, integration has proven a serious problem, especially in cities such as Bradford, or parts of London such as Tower Hamlets; and there are signs that, as time passes, assimilation is becoming harder, not easier. A 2007 report by British think tank Policy Exchange, Living Apart Together, revealed that members of the younger generation were more radical and orthodox than their fathers and grandfathers – a reversal almost certainly unprecedented within an immigrant population over three or more generations. The same pattern may be found across Europe and the United States. A visible sign of this desire to stand out from mainstream society is the steady growth in the numbers of young Muslim women wearing niqabs, burqas, and hijabs – formerly merely a tradition, but now apparently seen as an obligatory assertion of Muslim identity.

In Germany, the number of Salafists rose by 25% in the first half of 2015, according to a report from The Clarion Project. Salafism is a form of Islam that insists on the application of whatever was said or done by Muhammad or his companions, brooking no adaptation to changing times, no recognition of democracy or man-made laws. This refusal to adapt has been very well expressed by Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini:

“Islam is not constrained by time or space, for it is eternal… what Muhammad permitted is permissible until the Day of Resurrection; what he forbade is forbidden until the Day of Resurrection. It is not permissible that his ordinances be superseded, or that his teachings fall into disuse, or that the punishments [he set] be abandoned, or that the taxes he levied be discontinued, or that the defense of Muslims and their lands cease.”

The greatest expression of this failure to integrate, indeed a determined refusal to do so, may be found in the roughly 750 zones urbaines sensibles in France, Muslim-dominated no-go zones, which the police, fire brigades, and other representatives of the social order dare not visit for fear of sparking off riots and attacks. Similar zones now exist in other European countries, notably Sweden and Germany.

In the UK, matters have not reached the pitch where the police and others dare not enter. But in some Muslim-dominated areas, non-Muslims may not be made welcome, especially women dressed “inappropriately.” According to the 2011 British census there are over 100 Muslim enclaves in the country. “The Muslim population exceeds 85% in some parts of Blackburn,” notes the scholar Soeren Kern, “and 70% in a half-dozen wards in Birmingham and Bradford.” There are similarly high figures for many other British cities.

Maajid Nawaz of the anti-extremist Quilliam Foundation has spoken of the growing trend for some radical young Muslims to patrol their streets to impose a strict application of Islamic sharia law on Muslims and non-Muslims alike, in direct breach of British legal standards.

In Britain “Muslims Against the Crusaders” have recently declared an Islamic Emirates Project, in which they are seeking to enforce their brand of sharia in 12 British cities. They have named two London boroughs, Waltham Forest and Tower Hamlets, among their targets. Little surprise then that in these two boroughs hooded “Muslim patrols” have taken to the streets and begun enforcing a strict view of sharia over unsuspecting locals. The “Muslim Patrols” warn that alcohol, “immodest” dress and homosexuality are now banned. To add to these threats, all this is filmed and uploaded onto the internet. Now, in East London, some shops no longer feel free to employ uncovered women or sell alcohol without fear of violent payback.

Nawaz goes on to write: “[T]he Muslim patrols could become a lot more dangerous and, perhaps willing to maim or kill if they are joined by battle-hardened jihadis.” Muslims have been beaten up for smoking during Ramadan; non-Muslims have been forced to leave for carrying alcohol on British streets.

A recent report by Raheem Kassam cites British police officers who admit that they often have to ask permission from Muslim leaders to enter certain areas, and that they are instructed not to travel to work or go into certain places wearing their uniforms.

Here is the fulcrum around which so much of the problem turns: the belief that Islamic law has every right to be put into practice in non-Muslim countries, and the insistence that a parallel, if unequal, legal system can function alongside civil and criminal law codes adhered to by a majority of a country’s citizens. More than one non-Muslim has been ordered to leave “Islamic territory,” and some radicals have attempted to set up “Shariah Controlled Zones,” where only Islamic rules are enforced. Stickers placed on lampposts and other structures declare: “You are entering a Shariah Controlled Zone,” where there can be no alcohol, no gambling, no drugs or smoking, no porn or prostitution, and even no music or concerts.

And that is not all. Soeren Kern wrote in 2011:

A Muslim group in the United Kingdom has launched a campaign to turn twelve British cities – including what it calls “Londonistan” – into independent Islamic states. The so-called Islamic Emirates would function as autonomous enclaves ruled by Islamic Sharia law and operate entirely outside British jurisprudence.

The Islamic Emirates Project, launched by the Muslims Against the Crusades group, names the British cities of Birmingham, Bradford, Derby, Dewsbury, Leeds, Leicester, Liverpool, Luton, Manchester, Sheffield, as well as Waltham Forest in northeast London and Tower Hamlets in East London as territories to be targeted for blanket Sharia rule.

All of this is, of course, illegal. The illegality could not be clearer. Here we see self-appointed disaffected Muslim entities, who take action to exercise the power of imposing law on the streets of European cities, and in practice the writ of Islamic law runs in many towns and cities. Not long ago, considerable numbers of Muslims from Paris and the surrounding region would enter the city and take over entire streets in order to perform the noon Friday prayer. Traffic was blocked, residents could neither enter or leave their homes, businesses had to close because customers could not reach them; and all the while, the police stood by, watching but not interfering, knowing that, if they acted to preserve the law a riot would ensue. Videos of these incidents are available online. In places where gangs of radicals operate as if they are a mafia, crimes such as honor killings, female genital mutilation (FGM), expulsion or worse of individuals considered apostates, and more, are known to take place. More commonly, many Western states are powerless to prevent forced and underage marriages, compulsory veiling, polygamy, and more.

The police, afraid of charges of racism and “Islamophobia,” are reluctant to take action: In 2014 and 2015, the police and social workers turned a blind eye for years to Muslim gangs grooming, prostituting, and raping young white British teenagers in cities such as Oxford, Birmingham, Rochdale and Rotherham. Professor Alexis Jay’s report on the situation in Rotherham alone showed serious failings on the part of several bodies from the police to social services. The offenses in these cases were, of course, a breach of sharia law, not an enforcement of it.[1] Yet there seems to have been an attitude, too, that Muslims are entitled to behave as they wish, and that British law enforcement is irrelevant. In the trial of nine men in Rochdale, Judge Gerald Clifton states in his sentencing that “All of you treated the victims as though they were worthless and beyond any respect – they were not part of your community or religion.” This statement alone seems to illustrate the heart of this problem.

But the clash between Islamic law and national law in several European countries has focussed more than anything on the establishment of sharia councils or sharia courts. These have provoked a wider debate than even Islamic finance, now well situated within the international banking system even though it is as if Germany under the Third Reich had its own banking system in which all transactions would go exclusively to strengthening the Third Reich. In the UK this year, it has been revealed that, in order to finance extensive repairs to the House of Lords and the House of Commons, a deal has been done to use Islamic bonds. One result of this is that peers and MPs will not be allowed to have bars or to consume alcohol on their own premises.

The Sharia court debate has been particularly intense in the United Kingdom, where attempts (some successful) to introduce sharia within the legal system have been made since 2008. Speaking to the London Muslim Council in July of that year, Britain’s leading judge, Lord Chief Justice Phillips, declared that he believed the introduction of sharia into the UK would be beneficial to society, provided it did not breach British law. It is that stipulation which has not been adhered to. Not many months earlier, in February, Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Britain’s leading churchman — also, as Phillips, with a seat in the House of Lords — expressed the view that it would be appropriate for British Muslims to use sharia. He argued that “giving Islamic law official status in the UK would help achieve social cohesion because some Muslims did not relate to the British legal system.” He went on to say,

“It’s not as if we’re bringing in an alien and rival system; we already have in this country a number of situations in which the internal law of religious communities is recognised by the law of the land … There is a place for finding what would be a constructive accommodation with some aspects of Muslim law, as we already do with some kinds of aspects of other religious law.”

That is where the debate began. Williams’s call for the introduction of sharia was rejected at once by the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, and by the Conservative peer and shadow minister for community cohesion and social action, Sayeeda Warsi. Warsi, herself a Muslim, argued as follows:

“The archbishop’s comments are unhelpful and may add to the confusion that already exists in our communities … We must ensure that people of all backgrounds and religions are treated equally before the law. Freedom under the law allows respect for some religious practices. But let’s be absolutely clear: all British citizens must be subject to British laws developed through parliament and the courts.”

One year before, however, sharia had already entered the country. An organization called the Muslim Arbitration Tribunal had set itself up on the basis of the 1996 Arbitration Act. It allows individuals and businesses to enter into mutually agreed consultation in which a third party decides between their competing arguments. Mutual agreement is, of course, the central plank on which the legislation is based. Muslim tribunals are limited to financial and property issues. They use sharia standards for intervention, not just between Muslims, but even between non-Muslims who wish to settle disputes using sharia standards. Since 2007, the MAT has opened tribunals in Nuneaton, London, Birmingham, Bradford, and Manchester. They are all considered legal, and their rulings can be confirmed by county courts and the High Court.

Acquiescence to the regularization of sharia within UK legal processes received a major boost for a short time when, in March 2014, the Law Society issued guidance to permit high street solicitors to draw up “sharia compliant” wills, even though these might discriminate against widows, non-Muslims, female heirs, adopted children and others. When the debate grew more heated and the Law Society was severely criticized, some months later it withdrew the guidelines and apologized for having introduced them at all. It was a healthy expression of the way open debate in democratic societies achieves results.

By that time, however, there were around 85 sharia councils operating — most of them openly, some behind the scenes, across the UK. They had all been granted recognition by the establishment. These councils are often confused with the arbitration tribunals, but are, in fact, quite different. A council (sometimes termed a court) functions as a mediation service — also legal in British law. However, the decisions of these councils have no standing under British law. They are usually composed of a small number of elderly men with varying degrees of qualification in Islamic law, and they generally issue advice or fatwas [religious opinions] based on the rulings of one or another of the main schools of Muslim law.

It is these councils that are the greatest cause for concern, especially the limited range of matters on which they issue judgements: marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance. In all of these areas, the concerns rest principally on the treatment of Muslim women. Among the leading critics of Sharia on these grounds is one of the most visionary members of Britain’s House of Lords, Baroness Caroline Cox.[2] The first thing she did after her elevation to the peerage was to set off in a 32-ton truck for Communist Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union, to bring medical supplies behind the Iron Curtain. She was one of the first Western politicians to take the threat of Islamism seriously, setting out her arguments in a 2003 book, The ‘West’, Islam and Islamism. Is ideological Islam compatible with liberal democracy? .

This concern with Islamism and its incompatibility with secular democratic norms focuses especially on the application of sharia law within countries such as the UK, where all citizens are considered to be equal under the law. Speaking about sharia courts in 2011, Baroness Cox declared,

“We cannot sit here complacently in our red and green benches while women are suffering a system which is utterly incompatible with the legal principles upon which this country is founded… If we don’t do something, we are condoning it.”

Recently, she authored a report entitled, A Parallel World: Confronting the abuse of many Muslim women in Britain today, published by the Bow Group. In it, she not only describes the problems faced by many Muslim women before Sharia councils, but provides extensive testimony from women who have been discriminated against and abused by these “courts.”[3]

In May 2012, Baroness Cox introduced her first Arbitration and Mediation Services (Equality) Bill in the House of Lords. The bill had its second reading in October that year, but went no farther. It was backed, however, by a considerable body of evidence presented in a document, Equal and Free?, from the National Secular Society. In June, 2015, Cox introduced a modified version of the bill. It had its second reading in October, and in November it reached the committee stage. It still has to pass a few stages before it may possibly move to the House of Commons, one day perhaps to receive Royal Assent and become law. It received a very warm reception from members of the Lords, with only one dissenting opinion, that of Lord Sheikh, a Muslim peer who sees little or no fault in anything Muslims say or do. However, the government minister, Lord Faulks, argued that current civil legislation is all that is needed to guarantee justice for Muslim women.

Matters are far from as simple as the government would like them to be. Sharia law is not a cut -and-dried system that can be easily blended with Western values and statutes. There is no problem when imams or councils hand out advice on the regulations governing obligatory prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, alms-giving, the appropriateness or inappropriateness of following this or that spiritual tradition, or even whether men and women may sit together in a hall or meet without a chaperone. For pious Muslims, those are things they need to know, and although the advice they may receive on some rulings will differ according to the school of law or the cultural practices of their specific community, that has no bearing whatever on British law.

But much more goes on beneath the surface. One problem is that it is difficult if not impossible to reform sharia. Legal rulings are fossilized within one tradition or another and given permanency because they are deemed to derive from a combination of verses from the Qur’an, the sacred Traditions, or the standard books of fiqh or jurisprudence. It is, therefore, hard to restate laws on just about anything in order to accommodate a need to bring things up-to-date within terms of modern Western human rights values. Many Muslims today may be uncomfortable about the use of jihad as a rallying cry for terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State, but no single scholar or group of scholars is entitled to abolish the long-standing law of jihad. Innovation (bid’a) is tantamount to heresy, and heresy leads to excommunication and hellfire, as has been stated for centuries. The growing influence of Salafi Islam is based precisely on the grounds that any revival of the faith means going back to the practices and words of Muhammad and his companions, not forwards via reform.

In the sharia councils there appears to be no formal method for keeping records of what is said and decided on. There is next to no room for non-Muslims to sit in on proceedings, and, as a result, neither the government nor the legal fraternity has any regular means of monitoring proceedings. Even Machteld Zee, whose forthcoming book, Choosing Sharia? Multiculturalism, Islamic Fundamentalism and British Sharia Councils, will be the first academic analysis of what happens in the councils, only spent two afternoons at a council in Leyton and an afternoon at one in Birmingham. Unannounced spot checks by qualified government-appointed personnel are not permitted. There is nothing remotely like the government schools inspection body, Ofsted, which has periodically (albeit not always correctly) gone into Muslim schools. So there is really no way of knowing just what happens, apart from the testimonies of women who have reported abusive or illegal practices.

Magistrates’ courts, county courts, and crown courts are all entirely transparent (except for matters dealt with in camera), full records are kept, and members of the public are free to visit and observe. The risks of allowing councils to pass judgements without there being an inspectorate to observe them are obvious. And if full records of proceedings are not kept, it will always be difficult to go back to examine a case in full should legal issues arise at a later date.

Furthermore, the British legal system has no say in the appointment of sharia council panels. There appears to be no agreed mechanism for appointments, and the source and identity of candidates remain causes for concern in several ways. There is no single range of qualifications for Muslim scholars (‘ulama) or jurisprudents (fuqaha’). Most will attend some sort of madrassa [Islamic religious school], and many will sit at the feet of a particular sheikh to obtain an ijaza from him: usually this means he is given permission to teach from a book written by that sheikh. Some will finish a course of study, but there may be little coherence. Growing numbers have qualifications from UK-based madrassas, notably from the Darul-Uloom in Bury or the higher standard equivalent in Dewsbury, although there are other Darul-Ulooms in the UK. In London, the junior classes are inspected by Ofsted, others not. Bury and other madrassas belong to the radical Deobandi form of Islam (based in northern India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan). The Pakistani madrassas from which the Taliban emerged were and are Deobandi in belief. Many Saudi-funded madrassas in Pakistan have been used to recruit for jihad.

The Wahhabi-influenced Deobandis control a majority of mosques in Britain, but they are far from the only group with mosques and other institutions.[4] There are also smaller numbers of Salafi imams and scholars, many of whom come from Saudi-funded madrassas.[5]

This situation grows more complicated when one adds the larger numbers of scholars and jurisprudents emerging from colleges in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. These tend to be very conservative and still play a major role providing imams and members of Sharia councils.

In sum, these variations in training, qualifications, linguistic abilities, and so on mean that there is no level playing field for expertise, but that there is considerable latitude with regard to the interpretation of sharia law. Very often, scholars with adherence to one branch of Islam will violently disagree with others. It is generally reckoned that sharia councils and Muslim Arbitration Tribunals are conservative, with few advocates for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in sight.

Finally, there is a less-known feature of modern sharia theory that impacts on Europe, North America, and elsewhere in the West. In classical Islamic theory, the world is divided between the Realm of Islam (Dar al-Islam), territories ruled by Islamic governments, and the Realm of War (Dar al-Harb), regions under non-Muslim control. Strictly speaking, a Muslim who finds himself living in a non-Muslim country is obliged to leave it and return to a Muslim state, usually somewhere within a Muslim empire. Strictly speaking, it is proper, even obligatory, for Muslims to live in non-Muslim countries when those countries are under Muslim rule, regardless of the size of the two populations. All the early Islamic empires had a majority of non-Muslims. Muslim expansion and imperialism meant that Muslims controlled territories where, at first, they were not in a majority. These territories were considered as Dar al-Islam. Later, when Muslims were expelled from places such as Portugal and Spain, those countries became Dar al-Harb and in the view of many Muslims, it became necessary to fight them in order to return them to Islam, as is happening with regard to Israel today.

When, in the 19th and 20th centuries, non-Muslim forces took control of Muslim lands, compromises became necessary. However, during the late 20th century and increasingly in the current one, large numbers of Muslims came to live in Western countries. With the 2015 influx of refugees into Europe, Muslims living outside Islamic territories have been faced with dilemmas about the application of sharia, especially where it conflicts with the civil laws of their host countries.

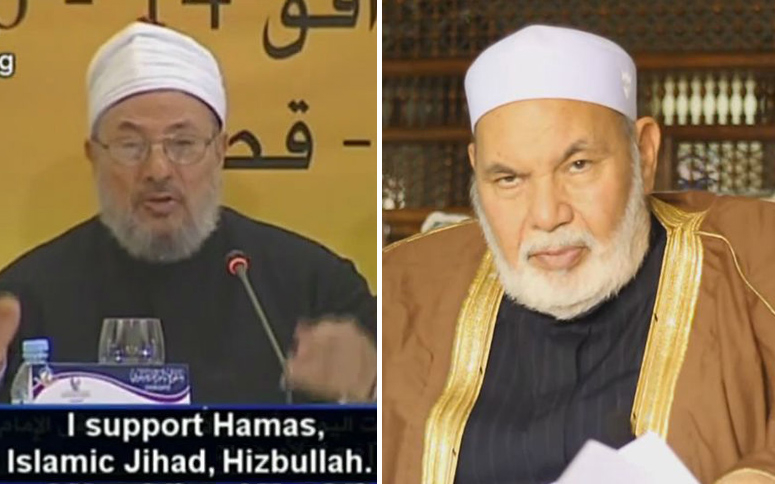

The response of many Muslim scholars has been to develop a new form of Islamic jurisprudence, fiqh al-‘aqaliyyat, “jurisprudence of the minorities.” This began in the 1990s, mostly through the efforts of two Muslim scholars, Shaykh Taha Jabir al-Alwani and Shaykh Yusuf al-Qaradawi. Alwani is president of the Graduate School of Islamic and Social Sciences in Ashburn, Virginia (now part of the Cordoba University), and is the founder and former president of the Fiqh Council of North America, an affiliate of the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA). ISNA itself has, of course, long been identified as a front organization for the hardline Muslim Brotherhood. That connection becomes more visible when one looks at Qatar-based Yusuf al-Qaradawi, one of the leading ideologues of the Muslim Brotherhood. Qaradawi’s television program, al-Sharīʿa wa al-Ḥayāh, attracts an international following of some 60 million, and his comprehensive online fatwa site, Islam Online is consulted by millions.

The Muslim scholars Yusuf al-Qaradawi (left) and Taha Jabir al-Alwani (right) developed a new form of Islamic “jurisprudence of the minorities,” which partly concerns whether non-Muslim countries with large Muslim minorities are still considered the “Realm of War.”

The principles under which the jurisprudence for minorities operates are somewhat complex. Part of the debate concerns whether non-Muslim countries with large Muslim minorities are still the “Realm of War;” the notion is generally rejected. If Western states are not in a state of war with Islam, then Muslims are not obliged to leave them to seek refuge in an Islamic country. In that event, it is necessary to interpret sharia rulings to make it possible for Muslims to live in territories to which they have migrated, or in which they find themselves for limited periods, as in staying abroad to study. However, adjustments to Western ways do not permit actual change to sharia.

In 1997, the government of Qatar provided funding to establish an institution known as the European Council for Fatwa and Research, based in Dublin, Ireland. The council, whose president is Qaradawi himself, was set up under the auspices of the Federation of Islamic Organizations in Europe, another front for the Muslim Brotherhood, with close associations to the Muslim Brotherhood’s Palestinian branch, Hamas. The ECFR has 32 members, roughly half from European states, the rest from North America, North Africa, and the Gulf. Its fatwas do little to integrate sharia norms within European societies. One fatwa declares:

“Sharia cannot be amended to conform to changing human values and standards; rather, it is the absolute norm to which all human values and conduct must conform; it is the frame to which they must be referred; it is the scale on which they must be weighed.”

The true significance of the ECFR and its international cast of member jurists is that it is an extra-territorial body that passes judgements, provides legal solutions, and adjudicates on all aspects of Islamic law. Its impact on national sharia courts, such as the British Muslim Arbitration Tribunal and the UK Islamic Sharia Council, cannot be calculated easily, but is certain to play an important role. If one reads the fatwas of the ECFR and the many online fatwa sites, it is clear that national sharia bodies in Western countries are operating outside the confines of British, French, and other legal systems. No European or American state can exercise full control over who serves on such councils, who influences them, and which rulings inspire their judgements.

Although the ECFR is the leading fatwa body in Europe, several other national organizations — in France, Germany, and Norway, for example — issue fatwas in other languages. Everywhere, the approach is much the same. Whether through conventional jurisprudence or the jurisprudence of minorities, there seems no clear path to improved assimilation of Muslims into European societies, and no accommodation of sharia law alongside Western, man-made law.

Unless reform enters the thinking of the Muslim clergy, Salafi Islam will continue to beckon Muslims to the past. Under strict sharia, the question remains: what is to become of the growing millions of newcomers for whom Western law codes are of secondary value — for whom they are, perhaps, just an obstacle in the path towards an ultimate goal of total separation from host societies?

In Sharia Law or One Law for All, I drew attention to another level of sharia rulings that provide fatwas for numbers of British Muslims, in particular of the younger generation. These are online sites: “fatwa banks.” Individuals or couples send questions to the muftis who run the sites, and receive answers in the form of fatwas that are considered authoritative. The questions and answers are preserved in galleries of rulings, which can be browsed by anyone seeking advice. The sites are by no means consistent, differing from one scholar to another. But they do provide an insight into the kinds of rulings that may be given in the sharia councils.

For example:

a Muslim woman may not marry a non-Muslim man unless he converts to Islam (such a woman’s children will be separated from her until she marries a Muslim man)

polygamous marriage (two to four wives) is legal

a man may divorce his wife without telling her about it, provided he does not seek to sleep with her

a husband has conjugal rights over his wife, and she should normally answer his summons to have sex (but she cannot summon him for that)

a woman may not stay with her husband if he leaves Islam

non-Muslims may be deprived of their share in an inheritance

a divorce does not require witnesses (a man may divorce his wife and send her away even if no one else knows about it)

re-marriage requires the wife to marry, have sex with, and be divorced by another man

a wife has no property rights in the event of divorce (which may be initiated arbitrarily by her husband)

sharia law must override the judgements of British courts

rights of child custody may differ from those in UK law

taking up residence in a non-Muslim country except for limited reasons is forbidden

taking out insurance is prohibited, even if required by law

there is no requirement to register a marriage according to the law of the country

it is undesirable to rent an apartment belonging to a Christian church

a Muslim lawyer has to act contrary to UK law where it contradicts sharia

employment by driving a taxi is prohibited

it is allowable to be a police officer, provided one is not called upon to do anything contrary to the sharia

women are restricted in leaving their homes and driving cars

an adult woman may not marry anyone she chooses

sharia law of legitimacy contradicts the Legitimacy Act 1976

a woman may not leave her home without her husband’s consent (a restriction that may constitute false imprisonment)

legal adoption is forbidden

a man may coerce his wife to have sex

a woman may not retain custody of her child after seven (for a boy) or nine (for a girl)

a civil marriage may be considered invalid

sharia law takes priority over secular law (for example, a wife may not divorce her husband in a civil court)

fighting the Americans and British is a religious duty

recommendation of severe punishments for homosexuals

a woman’s recourse to fertility treatment is discouraged

a woman cannot marry without the presence and permission of a male guardian (wali)

if a woman’s ‘idda (three months, to determine whether or not she is pregnant) has expired and she no longer has marital relations with her husband, he is excused alimony payments

an illegitimate child may not inherit from his/her father.

Some of these fatwas advise illegal actions and others transgress human rights standards as they are applied by British courts. They show vividly just how questionable it is to permit a parallel system of law within a single national system.

**Denis MacEoin is the author of “Sharia Law or One Law for All” (London, Civitas, 2009).

[1] See Ahmad ibn Naqib al-Misri, Umdat al-salik, trans. Nuh Ha Mim Keller as Reliance of the Traveller, Beltsville MD, 1991 and 1994, p. 595, o7.3: “As for when an aggressor is raping someone whom it is illegal for him to have sexual intercourse with, it is permissible to kill him forthwith,” based on a statement from Abu’l-Hasan al-Mawardi, the famous Shafi’i jurist (972-1058).

[2] Baroness Cox was made a peer in 1982, and since then has made an astonishing contribution to humanitarian causes worldwide, travelling to far-flung zones of conflict and human rights abuse, even at great personal risk.

[3] Similar views had been expressed two years earlier, in a 2010 report by Maryam Namazie’s One Law for All organization, Sharia Law for Britain: A Threat to One Law for All and Equal Rights. That report, in turn, had been preceded by a book, entitled Sharia Law or ‘One Law for All’?, written by the present author for the independent think tank, Civitas (the institute for the study of civil society).

[4] Other Muslims of Pakistani origin have a Sufi-influenced Barelwi orientation, which, although it adheres to the same Hanafi law school, is constantly in conflict with the Deobandis. There are certainly more young Muslims training in the UK, and many of these experience difficulty with courses taught in Urdu, as at Bury.

[5] For fuller details, see Innes Bowen, Medina in Birmingham, Najaf in Brent: Inside British Islam, London, 2014.

© 2016 Gatestone Institute. All rights reserved. No part of the Gatestone website or any of its contents may be reproduced, copied or modified, without the prior written consent of Gatestone Institute.