Two Potential Safe Zones in Northern Syria

Fabrice Balanche/Washington Institute/February 24/16

Both Idlib province and eastern Aleppo province have been relatively spared from the fighting, and their rural communities remain strong.

Read more articles from the TWI series on Syrian safe zones.The major battle taking place around Aleppo may ultimately result in two million Syrians attempting to enter Turkey from northwestern Syria

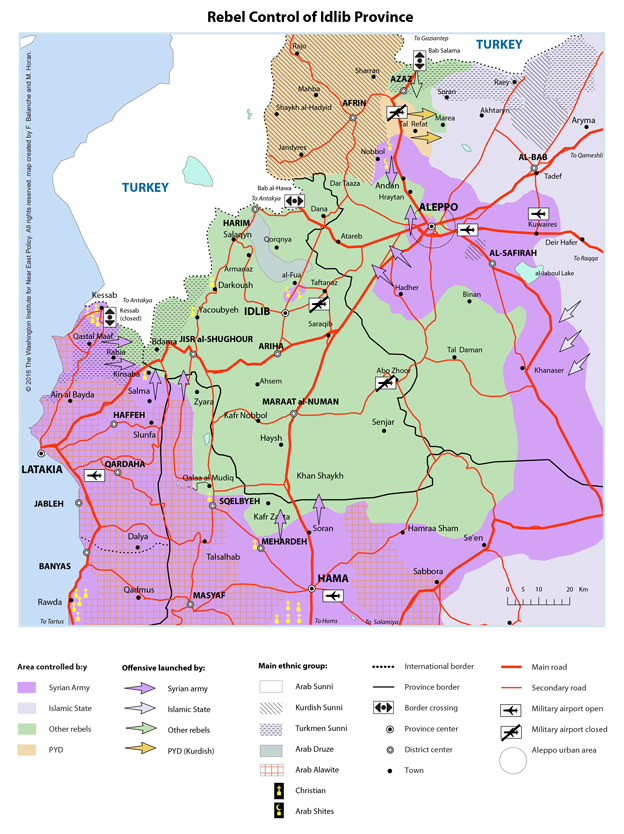

This is because the Syrian army’s counterinsurgency strategy — and that of its allies — is founded on expelling civilians first, which allows for easier clearing out of the rebels. In northwestern Syria, however, two potential safe zones exist outside the Kurdish and government-held areas. The first is centered in the rebel-held Idlib province, the second in the eastern part of Aleppo province, currently under Islamic State control. A description of these areas can help elucidate their potential as safe zones.

IDLIB PROVINCEAfter Raqqa, Idlib became the second provincial capital lost by Damascus, falling in spring 2015 to Jaish al-Fatah (Army of Conquest) along with the province’s two other major cities, Jisr al-Shughour and Ariha. Damascus had lost control of the countryside in winter 2011-2012.With a prewar population of about two million, Idlib province now has no more than 1.2 million inhabitants, with the balance having moved to other provinces or having sought refuge in Turkey. In its most recent evaluation, in August 2014, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimated that Idlib province had 708,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs).

The province, meanwhile, has a fairly homogeneous ethno-religious population consisting of 95 percent Sunni Arabs. During the countryside fighting of 2011-2012, and in Idlib city in March 2015, Christians fled as rebels took control. In particular, former residents of the Armenian village of Yacoubiyah transplanted themselves en masse to the Karabakh-Nagorno region, which straddles eastern Armenia and southwestern Azerbaijan. The towns of al-Fua and Kefraya host large Shiite communities, surrounded by rebels since Idlib’s fall, and ten Druze villages are scattered in Jabal al-Summaq.

Although proponents of the Shiite principle of taqqiya (dissimulation) proclaimed their support for the Syrian revolution early on, they are unsurprisingly suspected of munafiq (insincerity) by Jabhat al-Nusra. To the north of Jisr al-Shughour, a Turkmen population lives close to the Turkish border.

CLICK ON MAP TO VIEW HIGH-RESOLUTION VERSION.

Before the Syrian crisis began, 70 percent of Idlib’s population lived in the countryside, a fertile agricultural area that produces grains, olives, and winter vegetables, with individual irrigation allowing for additional crops in summer. For those who have remained, agriculture has provided a means to survive the turmoil. Even before the war, the area had very little industrial activity, and Idlib was known as an administrative city. Also, whereas in the prewar years Idlib province depended heavily on Aleppo for manufactured products, today everything comes from Turkey. Yet even supplies from Turkey are severely limited, with humanitarian convoys only able to reach Bab al-Hawa. Strict Syrian control of this border can be traced to the lingering Syrian claim on the “Sanjak of Alexandretta” — today’s Hatay province of Turkey. Indeed, barbed wire, no-man’s-land, and minefields mark the border between Syria and Turkey. Whereas today the Bab al-Hawa border cannot be crossed except in very select humanitarian cases, this was not the reality before 2015 and the huge migration to Turkey. In the earlier war years, Syrians could make return trips to Turkey or take refuge when fighting surged.

EASTERN ALEPPO PROVINCE

Like Idlib province, eastern Aleppo province quickly fell from state control and was relatively untouched by fighting between the Syrian army and rebels. However, during winter 2013-2014, rebels and the Islamic State clashed violently, as throughout northern Syria, with IS holding the area even as the group was expelled from Aleppo city and the province’s western section. In the Azaz corridor, the Islamic State and the rebels continue to face each other down and sometimes fight (see PolicyWatch 2532, “

But overall, the area has been fairly quiet and free of bombardment, with the Islamic State imposing its laws but at the same time providing relative safety to the population. Now, however, developments suggest the calm may not last. The Syrian army launched an offensive from the southwest (al-Safira) to lift the IS siege of the Kuwaires military airport before stopping ten kilometers south of al-Bab. To the east, the Kurds crossed the Euphrates River in late December 2015 by seizing Tishrin Dam. The People’s Defense Units (YPG), the Syrian Kurdish group, are stationed ten kilometers from IS-controlled Manbij, with plans to eventually launch an offensive against the city. To the north, the Turkmen brigade Sultan Murad, which has seized several villages along the Turkish border, enjoys Turkish artillery support. This pro-Turkish militia appears to be eying Jarabulus as its next target to prevent the YPG from seizing it from its Kobane position.

CLICK ON MAP TO VIEW HIGH-RESOLUTION VERSION.

Eastern Aleppo province is highly coveted and could quickly erupt into widespread violence. Distinct from rebel-held Idlib, this territory — because under IS control — will likely be conquered by either pro-Russian or pro-Western forces. Like with Idlib province, however, the difficult question remains of how to protect civilians once the Islamic State is ousted.Similar to the 2010 figure, eastern Aleppo province now has some 700,000 inhabitants. This stability owes in part to the limited fighting, with refugees to Turkey being replaced by IDPs from Aleppo city. OCHA’s 2014 estimate cites 600,000 IDPs in eastern Aleppo province, but this figure may well have been exaggerated by the Syrian opposition to obtain more humanitarian aid. As in Idlib, eastern Aleppo’s main economic activity is agricultural, so the population’s basic needs remain largely satisfied. Manufactured goods, medicines, and other items are transported from Turkey without difficulty.

This transit of goods has remained steady, with Syrian oil flowing in the other direction, even as civilian visits to Turkey have been restricted since the November 13, 2015, Paris attacks.Eastern Aleppo’s population is now 100 percent Sunni. Christians were rare even before 2010, but the last of the Christian families fled with Alawite civil servants in 2012. However, ethnic diversity is stronger than religious diversity, with Kurdish and Turkmen minorities holding a position that is difficult to estimate. Many villages are mixed, and these ethnic groups’ representation is unknown in the urban areas of Manbij, al-Bab, and Jarabulus. This demographic ambiguity is meaningful, especially among the Kurds, who claim the area is historically Kurdish. A major confrontation could therefore occur once the Islamic State leaves, unless precautions are taken to fill the political vacuum.

SAFE ZONES AND RURAL RESILIENCE

Both Idlib province and eastern Aleppo province have been relatively spared from the Syrian fighting. Rural communities remain strong and generally benefit from effective basic services and distribution of humanitarian aid provided through their local governments. Although these two areas are virtually self-sufficient when it comes to food, maintaining an open gate to Turkey is essential, especially for medication and health services. A safe zone in either region, therefore, could promote the return of refugees and IDPs to the villages and small towns even absent full public services. Indeed, former rural inhabitants of these areas will be more accustomed to enduring spartan living than urban dwellers would be. And establishing decent conditions for return is far more complicated in large cities, where infrastructure was destroyed, than in villages and small towns. As part of a general ceasefire, economic relations are likely to resume quickly between the regime zone and the rebel zone, which could facilitate economic development and the return of the refugees and IDPs.

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.