What Turkey’s Election Results Mean

Soner Cagaptay/Washington Institute

June 09, 2015

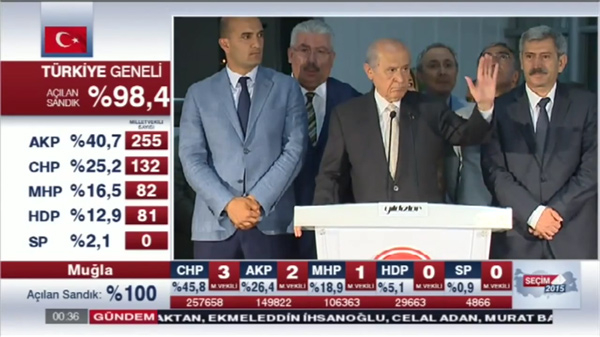

The outcome has dealt a blow to the AKP’s longstanding dominance and Erdogan’s goal of implementing a presidential system, with potential implications for the economy, Syria policy, and the Kurdish movement. This weekend, Turkey’s governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost its thirteen-year parliamentary majority. According to unofficial results from the June 7 elections, its vote tally dropped to 41 percent, down from 50 percent in 2007.

Elsewhere, the main opposition faction — the leftist Republican People’s Party (CHP) — saw its support drop from 26 percent to 25 percent, while the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) boosted its tally from 13 percent to over 16 percent. And the smaller Kurdish nationalist Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) more than doubled its support, winning 13 percent on a liberal platform that reached out to women as well as political and ethnic minorities.

Preliminary results indicate that the AKP will hold 258 seats in the 550-seat legislature, CHP 132, MHP 80, and HDP 80. Since no party holds a majority, the next government will be either a coalition or minority government. The AKP can form a coalition with just one partner, whereas the other parties need at least two partners to muster a majority. In theory, many coalition permutations exist, but in reality the options are limited because the MHP and HDP have, at least for the moment, ruled out coalition with the AKP, and the MHP has ruled out coalition with the HDP. Left-right coalitions are unlikely in Turkey, suggesting that an AKP-CHP government may not be in the offing, though such an alliance could deliver much-needed stability and social harmony by bringing the country’s disparate halves together. A left-left CHP-HDP coalition is not possible because their total seat tally would not be enough to secure a vote of confidence. The political alignment points in the direction of a minority government, unless the two right-wing parties, the AKP and MHP, can form a government in which President Recep Tayyip Erdogan agrees to take a step back — a highly implausible scenario.

Alternatively, the country could face early elections. The Turkish constitution dictates that a government must be formed within forty-five days after elections. If no government has received a vote of confidence in the legislature by this deadline, new elections have to be called.

OTHER IMPLICATIONS

For Erdogan: His ambitions to become Turkey’s first executive-style president have been vetoed by the electorate. The MHP, CHP, and HDP have all ruled out the status quo — whereby Erdogan effectively runs the country behind the scenes — as a precondition for entering a coalition government with the AKP. His party may still form a government or come back as the majority party in likely early elections, but Erdogan’s presidential ambitions are now exhausted. Nevertheless, he will continue his efforts to run the AKP and pursue an executive-style presidency, albeit with different tactics — especially if early elections usher in a more pro-Erdogan alignment.

For short-term Turkish politics: No coalition or minority government in Turkey has ever finished its term, and the country usually witnesses political and economic crises when such governments fail as a result of bickering between coalition partners. Should Turkey enter a period of political or economic instability under a coalition government or during the forty-five-day formation process, the public may be swayed to support a single-party AKP government again in early elections. Conversely, the opposition could paint the AKP as the problem, increasing its own support in such elections.

For long-term Turkish politics: The results have proven that Turkey is too big and diverse for President Erdogan, the AKP, or any other party to control singlehandedly. The economic miracle that Erdogan ushered in over the past decade has become his nemesis. He helped make Turkey a middle-class society, but that constituency has now found a voice in the parliament through the Kurdish-liberal alliance and the CHP. The liberals are Erdogan’s greatest long-term challenge. With a record number of women (who now constitute nearly 20 percent of the legislature), young members, and ethnic, religious, and political minorities (e.g., Armenians), this will be the most diverse Turkish parliament ever.

For Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu: This was an awkward election for him because he essentially ran a campaign to eliminate his position, telling the electorate, “Vote for me so you can get rid of me, and then make Erdogan the formal head of government.” This gambit failed, but he had no other choice — Erdogan ran the AKP’s campaign.

For the Kurds: This is a chance for the pro-democracy wing of the Kurdish nationalist movement to finally take over its violent wing. The HDP has entered the parliament thanks to support from liberal Turks, showing that democracy is the solution to Kurdish grievances — and, more important, that the movement’s future is intertwined with that of liberal, democratic Turkey.

For Syria policy and U.S.-Turkish ties: The AKP has been nearly obsessed with ousting the Assad regime in Damascus and has used most any means to achieve this end, such as allowing radical fighters to flow across Turkey’s borders. Now that the party has lost its legislative majority, this policy will come under greater parliamentary, media, and public scrutiny. As a result, Ankara may come down a notch to a policy that involves taking smaller steps toward removing Assad, akin to Washington’s policy.

**Soner Cagaptay is the Beyer Family Fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute, and author of The Rise of Turkey: The Twenty-First Century’s First Muslim Power, named by the Foreign Policy Association as one of the ten most important books of 2014.