◾Erdogan is not happy with the powers the Turkish constitution grants him. He wants more.

◾Once he has given orders, there should not be judicial, constitutional or parliamentary checks and balances. He will become the first ballot-box Sultan of the Turkish Empire of his dreams.

◾367 parliamentary votes are required to pass a constitutional amendment in parliament without a referendum, and at least 330 to make Erdogan an elected Sultan. But if he wins, he will be the president of less than half of the Turks, with the other half hating him more than ever.

It is election time in Turkey. On June 7, the Turks will go to the ballot box to elect a government and a prime minister who will rule the country for four years. In reality, they will go to the ballot box to decide whether they want an elected Sultan or not. Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, wants more than just to win a parliamentary majority for his Justice and Development Party (AKP). He wants a two-thirds majority, so that the constitution can be amended to introduce an executive presidential system and the Sultan can once again officially rule.

In 2013, Burhan Kuzu, the AKP’s chairman of the parliament’s Constitution Commission, compared the U.S. presidency to the broad powers of Turkey’s prime minister (who at the time was Erdogan), saying, “Obama is a poor man, the Prime Minister is powerful.”

More recently, during a press briefing after a state visit to Kazakhstan, Erdogan told a group of Turkish journalists on April 18: “Look now. Obama cannot get decisions done.”

It was just another line with which he expressed his obsession to transform Turkey’s parliamentary democracy into an executive presidential system “a la Turca,” in which an elected man runs a one-man show with no checks and balances. The powers the Turkish president has do not satisfy Erdogan. He is the strongman, but he wants more. He wants almost unlimited powers: He wants to be the democratically elected Sultan of a supposed emerging Turkish empire.

Despite constitutional articles that require the president to be non-partisan in domestic politics, Erdogan has been running from one public rally to another bashing opposition parties and praising the ruling AKP’s “success stories” since the party came to power over 12 years ago. Erdogan constantly says that he wants 400 MPs. He does not say for which party he wants 400 MPs. He does not have to — everybody knows. It is the first time a Turkish president, supposedly non-partisan according to the constitution, tours the whole country in support of a political party.

Turkey has a 550-seat legislature. Any party (or parties in coalition) that wins 276 seats can form a government. But 330 votes are required to bring a constitutional amendment to referendum, and 367 to pass a constitutional amendment in parliament without a referendum. The AKP is fighting not for 276 seats to form a single-party government but, under the shadow of Erdogan, for at least 330 to make him an elected Sultan.

All opinion polls, including the opposition’s, put the AKP into the lead. Although it is almost certain that the AKP will be the winner, it may yet be the loser. If a pro-Kurdish party, the People’s Democracy Party (HDP) can pass the 10% electoral threshold to enter parliament, the AKP’s 40% to 45% majority will only win anywhere from 280 to 310 seats, thus unable to change the constitution in line with the Sultan’s wishes. Therefore, the key to understanding the aftermath of the June 7 election is to watch the HDP’s performance. If it fails to win 10% of the national vote, it will get no seats in parliament, and most of the seats it would have won will be AKP’s – courtesy of the Turkish electoral system.

With the same percentage of votes, the AKP can win 280 or 330 seats depending on whether the Kurdish party makes it into parliament or not, and thus fail or succeed in amending the constitution for an “a la Turca” presidency. Unfair? Not in a country where justice is mere triviality. Erdogan has won nine elections since 2002 – three parliamentary, three municipal, two referenda and one presidential. But he is not happy with the powers the Turkish constitution grants him. He wants more. He wants to be Turkey’s elected Sultan. He does not want to be a “poor Obama.” He wants, as he says, “to get decisions done.” Once he has given orders, there should not be judicial, constitutional or parliamentary checks and balances. His decisions should get done — just like a Sultan’s.

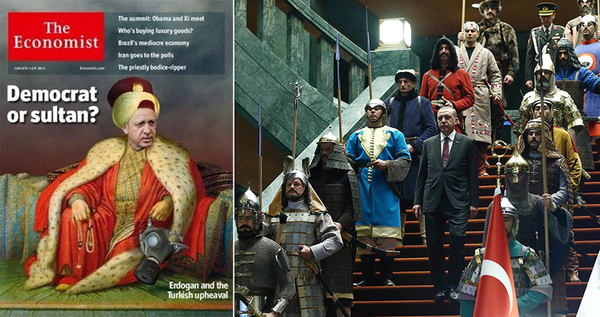

In 2013, The Economist published on its cover a photomontage of Ottoman Sultan Selim III and Turkey’s then Prime Minister (now President) Recep Tayyip Erdogan, to illustrate Erdogan’s growing autocratic tendencies (left). In 2015, Erdogan himself posed in his palace with the costumed “16 warriors” that guard him, who are meant to represent the 16 polities in Turkic history, including the Mughal empire, Timurid empire and Ottoman empire (right).

Ottoman sultans did not get elected. If Erdogan wins, Turkey will be even more polarized and increasingly less manageable: he will be the president not of the whole country, but less than half of the Turks, with the other half hating him more than ever. If he fails, an in-house fight within AKP will probably break out, with many unhappy but so far silent AKP political figures starting to fire in every direction. June 7 is all or nothing for Erdogan. He will either be the solitary man living in an isolated presidential palace in Ankara, hands tied by constitutional restrictions, still dreaming of a ballot-box sultanate, or he will become the first ballot-box Sultan of the Turkish Empire of his dreams.

**Burak Bekdil, based in Ankara, is a Turkish columnist for the Hürriyet Daily and a Fellow at the Middle East Forum.