Why the U.S. program for Syrian rebels will likely fail

Sunday, 10 May 2015

Sharif Nashashibi/Al Arabiya

A U.S.-led program to train and arm Syrian rebels, which has just begun, will at best be ineffective, and at worst a total failure that could inflame the situation on the ground, increase opposition infighting, and play into the hands of President Bashar al-Assad. Before it had even begun, American officials were “already scaling back expectations of its impact,” Reuters reported last week.

A fundamental issue is the program’s scope, which is limited to targeting the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), not the Assad regime, despite the latter committing war crimes and crimes against humanity against its own people long before the rise of ISIS. “Nothing has changed about the policy that there is not going to be a U.S. military solution to Assad,” Rear Admiral John Kirby, the Pentagon press secretary, said in late February.

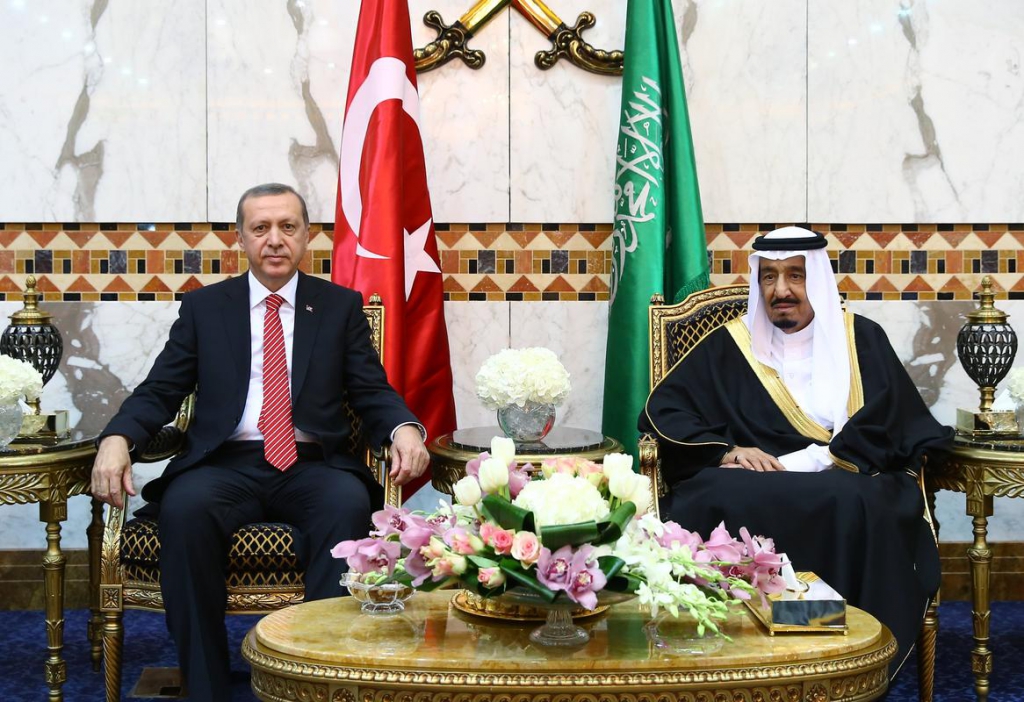

This jars with the insistence of Syrian opposition groups and important U.S. allies in the region – such as Turkey and Gulf states – that there should be no place for Assad in a post-conflict Syria.

Assad may rest assured that such a force will pose little if any threat to his grip on power, and may even help cement it. U.S.-led airstrikes against ISIS have allowed him to intensify attacks against other opposition groups (including those that have been at the forefront of the fight against ISIS from the start). Even American officials have acknowledged the benefit to the Syrian regime.

The new program will have much the same outcome. Washington has been accused of effectively supplementing Assad’s air force – now the accusation will be that it is bolstering his ground forces as well.

Assad’s calculus

Assad has said his army will fight the “illegal” U.S.-backed rebels. Given that the program poses no threat to him, this might just be bluster designed to galvanise his support base by being seen as standing up to the West. Certainly, his initial condemnation of the U.S.-led airstrikes against ISIS has given way to his calls for cooperation and intelligence-sharing with the West.

Assad could well sit back and watch the U.S.-backed Syrian rebels and ISIS wear each other out, and gain ground when either or both sides are weakened. Though some may be puzzled by his hostility to a program that will not target his forces, it can be seen as an extension of his long-held policy of using the lion’s share of his military resources against rebel groups fighting ISIS, rather than against the jihadist group itself.

Assad may be calculating that targeting the U.S.-backed rebels will not result in direct American retaliation. After all, despite months of planning, Washington has still not decided how extensively and under what circumstances it will back the force militarily. Defense Secretary Ash Carter said in March that the United States did not have clear-cut legal authority to protect Syrian rebels against regime attack.

When one also factors in paltry American support thus far – certainly compared to foreign support for Assad – and President Barack Obama’s reluctance to do more than talk tough against the regime – allowing, for example, the latter to cross his “red line” over the use of chemical weapons – none of this bodes well for the kind of cover that rebels in the program will need.

Obstacles

They could thereby end up simultaneously fighting two superior forces, or perhaps even more. They may well be viewed with suspicion or resentment by opposition factions outside the program, and outright hostility by powerful Islamist groups that are expressly excluded from it. The result could be increased fighting and division among rebel groups, at a time when greater coordination recently has resulted in significant gains against the regime.