Young Lebanese Armenians fervent about history and heritage

Apr. 24, 2015 /Ghinwa Obeid/The Daily Star

BEIRUT: “The Turks killed our people,” was the refrain repeated by Lebanese-Armenian students this week. Friday marks the 100th anniversary of the American Genocide, and the young students discussed with The Daily Star how the event shaped their history.“In 1915, when World War I began, when people where busy with the war, the Turks benefited from the situation so that they attacked us,” 14-year-old student Vartan Nechanian explained. At the Ecole Sainte Agnes in the heart of Beirut’s northeastern suburb of Burj Hammoud, Nechanian explained that the Turks wanted Armenians to belong to the museums only. “But they didn’t succeed,” he said proudly. “Now, we proliferated. We are everywhere. Everyone knows us and they’re recognizing the genocide.”

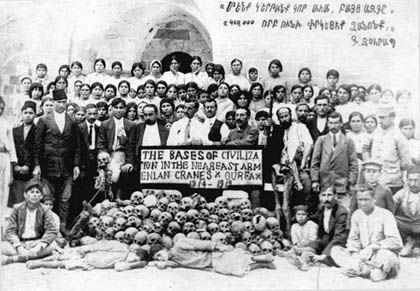

When Nechanian spoke, using the first-person plural, he reflected the sense of nationalism shared by Lebanese Armenians. On April 24, Armenians around the world will commemorate the centenary of the Armenian genocide. Turkish authorities killed 1.5 million people between 1915 and 1917, Armenians say, to eradicate Armenians from then-Anatolia. Those who survived fled and sought refuge in neighboring countries. With a couple of prompts from his academic adviser, the grade 8 Nechanian continued saying that the Turks were targeting Armenians “because they had lands and because they are smart.” “They took the smart ones first … they killed them, smashed their heads … they took the elite because they didn’t want them to direct people,” he said. “Then the youth were asked to join the war [World War I], but it was a trick and a similar fate awaited them,” Nechanian explained.

The children recount how ordinary citizens such as women, children and elderly people were asked to leave their homes and told they would be joining their husbands and other family members. They left and didn’t return as they were sent on marches without food or water. Many died along the way. “If the Turks saw that someone was carrying with them gold or money they used to take it,” Hagop Apanian, 10, said. “The Turks also used to tell beautiful [Armenian] women that they would marry them. But women refused and threw themselves in the sea,” he said from his grade 4 classroom at the Ecole Sainte Agnes. Armenians are a minority in Lebanon. Their relative closeness and historical struggles have kept the memory of the genocide alive among younger generations, many of whom were born in Lebanon and have gathered information about the genocide from what has been taught to them by families and schools. “During the war my grandmother was with her father and siblings,” said Mario Saboudjian, a student at the Lebanese National School in Burj Hammoud. “The Turks, she used to tell me, massacred her father in front of her. My grandmother along with her siblings hid for a week before Arabs, most probably Syrians, then saved them,” the 15-year-old added.

Up until now Turkey vehemently refuses to recognize the genocide, an issue that left strong feelings of resentment among Armenians across the world, including the young students. “Our lands are in the hands of the Turks,” said Johnny Torossian, 14, also an LNS student. “There’s the right of our ancestors that were massacred. There’s a people that was mascaraed. This is a crime that they [Turks] should pay the price for,” Torossian said emotionally. “I want them to give us back our country, our homes,” said Nechanian, the Ecole Sainte Agnes student. “I want them to give the 1.5 million martyrs that died during the war their right, and that’s recognition [of the genocide].”

MP: Armenians united in their demand for reparations

Ned Whalley/The Daily Star/Apr. 24, 2015/BEIRUT: Tashnag leader MP Hagop Pakradounian characterized the centenary of the Armenian genocide as both a memorial service and a call for justice, saying Armenians would never surrender to the ongoing assault on their presence in the region. “The mere fact that the Armenians are [still] present, that we are still talking about the Armenian question, that we are exerting pressure, that we are remembering and demanding, it means that the Turks couldn’t succeed in their plans.” Pakradounian said remembrance is particularly important to the Armenians in Lebanon, “because the diaspora is constituted of those who were subject to the genocide. My grandfather was killed in 1915. It’s very logical that I will have this grievance more, and this ‘fight against Turkey’ more, so I can take back my rights.”He said there would be a new emphasis this year on the universality of the tragedy, and a focus on how to prevent its repetition. “We are talking about collective remembrance, not only for the Armenians, but also for our Lebanese compatriots [who died in] the famine.”

Under Ottoman rule, nearly a third of the Mount Lebanon’s population perished from starvation and disease during World War I. Lebanon’s Armenian parties are split between the March 14 and March 8 alliances, but Pakradounian said they are united in gaining recognition of the genocide. “We had a united delegation to meet Prime Minister Tammam Salam and demanded that the 24th of April should be declared an official holiday.” He said one the largest issues facing the Armenian community is the influx of refugees from Syria. The community needs more assistance from the government and international organizations, he added. “We now have now around 12,000 Armenian refugees from Syria living here in Lebanon … hosted by Armenian families. The Armenian parties, the church, we take the [responsibility] of helping them.” Pakradounian sees the destruction of Armenian communities in Syria as part of a continued attack by Turkey, which he claims is trying to rid the Middle East of Armenians by supporting “terrorist” groups. “In March last year, they opened their borders to [the] Nusra [Front] and Daesh [ISIS], and they helped them logistically when they entered the Armenian town of Kassab … all the Armenians were deported from the town,” he added. But Pakradounian expressed optimism that Armenians would one day receive recognition, reparations and territorial concessions from Turkey, and pointed to Pope Francis’ recent recognition of the genocide as a sign of hope. “I am sure that after the pope’s declaration that most of the Catholic states will take further steps to recognize the genocide, and put pressure on Turkey to recognize it.” Talk of reparations is controversial in Turkey, and the restoration of ‘Western Armenia’ remains a dream, but one that Pakradounian insists Armenians have not given up on. “It’s true that politics is the art of possible, but there is nothing impossible in politics.”

Armenian elders tell tales of survival

Ned Whalley/The Daily Star/ Apr. 24, 2015/BEIRUT: As Burj Hammoud commemorates the centenary of the Armenian genocide, some of the neighborhood’s older residents recall the tragic stories from their parents and grandparents who were forced to flee in 1915. Vahram Karagouzian, an 83-year-old who runs a clothing shop just off the main street in Burj Hammoud, told a harrowing story of the death of his mother’s father at the hands of Ottoman soldiers. “One day he got married, and after getting married his wife was pregnant. The Turks came in the massacre of Adana at that time, and they cut [off] his arm. My grandmother [put her arms around him], and told them, ‘Leave him alone, you cut [off] his arm but don’t kill him.’ When she told them to not [kill him], they cut off the other arm. At that moment he died, his body couldn’t take it anymore.”

Around 20,000 to 30,000 Armenians were killed in the 1909 Adana massacre, a harbinger of the even larger disaster to come. Both of Karagouzian’s grandfathers were killed. “When my father’s mother was pregnant with him, they killed my grandfather. When they [deported] them to Jordan, he lost his mother [on the march]. So he didn’t know either his mother or his father.”He said his father spent time in orphanages in Jordan and Greece before traveling to his uncle’s family in Iskenderoun, in French mandate Syria. When the French soldiers left in 1939, the city reverted to Turkish rule. Fearing further persecution, his parents left with them. “When the French left they were obliged to leave. They left and came here. My mother, she used not to talk about [any of] this, but when she got old, in her last years, she began to talk about it and would cry.” Hripsime Der Bedrossian Balion, 70, owns an Armenian arts and crafts shop just around the corner. “My grandfather, my father’s father, died in deportation. They [were deported] to Syria and they suffered on the road … In the desert, he died,” she recalled. “[He had left with] his wife and two boys and one girl, the smallest one was 3 years old. In that region they had money, so they put the money in their clothes so no one could steal it. When she [arrived] in Syria, she used the [money] to educate and feed them.”

The stories of the Armenian diaspora are all marked with tragedy, but by virtue of being told by the families of survivors, they are sometimes also stories of resilience and escape. In a cafeteria on the second floor of his clothing shop, 67-year-old Haygazoun Zeytlian recounts the dramatic tale of his parents’ village of Musa Dagh, and their resistance to the Ottoman army. “My grandmother’s father, they took him [for the] Turkish army and when … they got to the army and saw what was happening, they fled, and came back to say that there is a genocide that is going to happen, there is something that is getting organized,” Zeytlian recalled. “So they all decided to get to the top of the village where there is a mountain, so they can be there and don’t get massacred, and they tried to [fend] off the army of Turkish army,” Zeytlian said. “On the top of that mountain they put a cross, and as they were trying to protect themselves … the French armies came with a ship, and they told them we are getting massacred. And the [French] told them give us one week so that we can manage to take you off this place and, after a week they came.”More than 4,000 people were evacuated from Musa Dagh by French and British ships. The villagers reportedly held out on Musa Mountain for 53 days. Zeytlian said the French transported them to Iskanderoun. Like the Karagouzians, his family left with the French forces in 1939 rather than come under Turkish rule. “Now all the Musa Degh people live in [the Bekaa Valley village of] Anjar. It’s an Armenian village.”“That’s how they survived. My father was 10 years old. They all told me the story: my mother, my father, my grandmother. The people who ran and came to tell them – if it wasn’t for those people, all of them would have been massacred.”