The Rummenigge (Amin al-Hajj) file opens: Mossad’s top agent in Lebanon speaks for the first time

He grew up with Imad Mughniyeh in Beirut; family members hold key positions in Hezbollah, and no less than nine death sentences await him in Lebanon – but for three decades, Amin al-Hajj (codename Rummenigge) was one of the most significant, sophisticated and audacious agents working for Israel in the Middle East. So why does he now say in an exclusive interview that Israel ‘threw me to the dogs’?

Ronen Bergman

Published: 11.14.14, 13:40 / Israel News

In the mid-1980s, senior Israeli intelligence officials began monitoring a new and dangerous development in the Middle East: Palestine Liberation Organization operatives, who just a few years earlier had been chased out of Beirut to Tunisia under Israel Defense Forces fire, were slowly but surely returning to Lebanon. For the intelligence officials this meant only one thing: The PLO was clearly rebuilding, and one of the few significant achievements of the First Lebanon War was about to be wiped out.

Follow Ynetnews on Facebook and Twitter

Israel’s intelligence systems began monitoring the PLO infiltration routes and soon learned that many of the terrorists were leaving their training camps in Tunisia and Libya and choosing to enter Lebanon via Cyprus, to which they would fly. Once in Cyprus, the PLO members would board yachts and small boats and head for Lebanese shores. The busy maritime lines between Lebanon and Cyprus, however, made it impossible for Israel to stop and check all of the many vessels in the area.

Israeli intelligence officials sought a solution – and then someone offered a suggestion: “Call Rummenigge.”

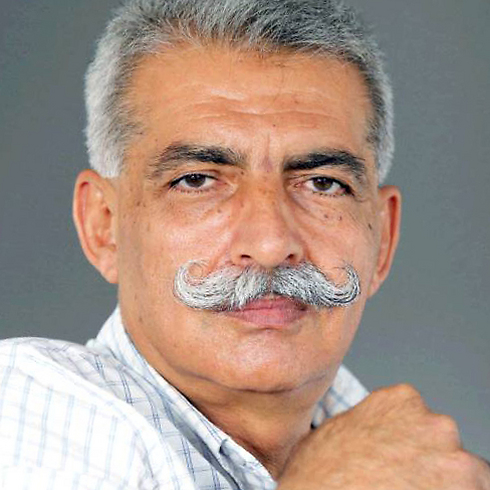

Rummenigge was the nickname the Israeli intelligence community had assigned to Amin al-Hajj, who was then one of Israel’s key agents in the region and thought of as a highly significant intelligence asset. A Shia Muslim of immense proportions, sharp-witted and unscrupulous, whose spectacular mustache made him a true legend in the espionage community, Rummenigge listened studiously to the problem posed to him and then he proposed his solution – prostitutes.

“I went out and recruited several high-class prostitutes who worked at a number of nightclubs in Limassol where PLO members used to hang out,” Rummenigge says of the network he set up in an exclusive interview with Yedioth Ahronoth. “Under the influence of alcohol and the pampering of these women, they would talk about what was happening – who’s coming, who’s going, and how he’s getting there.”

Rummenigge was the recipient of the information flowing from hotel bedrooms in and around Limassol; and to this intelligence provided by the prostitutes, he added information collected from Cypriot cab drivers, customs officials and elsewhere, and passed everything on to his handlers. From that point on, it usually went something like this: An Israel Navy missile boat, with prisoner interrogators from Unit 504 Military Intelligence on board too, would wait for vessels singled out by Rummenigge’s network.

“Our explicit objective was to capture them and not to kill them,” says a former Military Intelligence officer, “because we knew a proper and intensive interrogation would yield much more than a corpse floating at sea. It was easy to make them talk. The problem remained of course how to locate the ships from among the thousands of yachts and boats coming and going from Cyprus, and Rummenigge solved this problem for us.”

* * *

This wasn’t the only problem that Rummenigge solved.

For three decades, Amin al-Hajj served as one of the Israeli intelligence community’s most senior agents in the Middle East. He was at the center of a long list of hair-raising operations, most of which remain highly classified and not for publication. His efforts led to the capture of hundreds of terrorists, helped to uncover numerous tons of arms, and put his life at risk on more than one occasion.

Listening to al-Hajj’s monologues, one is immediately drawn into a dark world, seeped in intrigue, which sometimes sounds fantastical. But conversations I have held over the past months with senior officials in the intelligence community reveal that Rummenigge was indeed involved in numerous important intelligence affairs and operations. While some of these intelligence officials may remember him as an unruly agent, prone to extravagant and ostentatious behavior, there’s no disputing the bottom line: For years on end, Rummenigge was a huge intelligence asset for Israel, and his actions saved the lives of a great many Israelis and contributed significantly to the country’s security.

And now he’s going to war – not against the Palestinians, who tried so often to kill him; not against his Lebanese family, many of whom have joined Hezbollah and ostracized him; not against his Dahiyeh neighborhood friends, who have imposed nine death sentences on him; but in fact against the people who were his handlers and worked alongside him all those years.

“Israel’s security establishment has thrown me the dogs,” al-Hajj says in anger. “I’m living in Israel under an expired travel pass, without rights, without medical insurance, with only a few good friends who help me now and then and come to my rescue. They used me, extracted all they could from me, and I gave my heart and soul – and now they’ve tossed me aside like some kind of a rag.”

Hide-and-seek with Mughniyeh

Born in 1955 in al-Dahiyeh al-Janubiyeh (the southern suburb) in Beirut, Amin Abbas al-Hajj comes from one of the richest and most important families in Lebanon’s Shia community, the country’s largest and most influential ethnic group. In Dahiyeh, al-Hajj and his family lived on streets named after renowned family members – his father, grandfather and uncle; and a well-known Beirut printing house once printed a copy of the Koran that bore a picture on the front page of his father, Abbas al-Hajj – a very unusual step designed to demonstrate the tremendous respect for the man in the Lebanese capital.

Amin, the boy, was raised in a very religious home, a home that identified strongly with Lebanese nationalism, a home that hosted the country’s leaders, leading business executives, religious clerics and other people of influence; and saved on his cell phone are photographs of his father with presidents and prime ministers. His father had a special and close relationship with Lebanon’s pro-West president, Camille Chamoun, who was destined to play a crucial role in Rummenigge’s future.

Amin’s grandmother lived on the same street in Dahiyeh and he used to visit her almost daily. Armed with the candy she would give him, he’d go out onto the streets to play with the other neighborhood children. On one such day, he met a kid who would one day drench the Middle East in blood. “A group of children a little younger than me were playing outside my grandmother’s house, on Abbas al-Hajj Street,” Rummenigge recalls. “They knew that I candy from my grandmother and asked me to share some with them too. That’s when I met him – Imad.”

Imad is Imad Mughniyeh, who went on to become Hezbollah’s military commander and one of the most notorious terrorists to come out of the Middle East. Mughniyeh, too, came from a traditional Shia family, albeit far less respectable and wealthy than Amin’s. “His father was a worker at the Jabar sweets and biscuits factory in Beirut – a simple man. We were in contact as children,” al-Hajj says. “He was very naughty. Then I heard he had joined the Force 17 training camps and we lost contact.”

It wasn’t long before the young al-Hajj saw his country slide into a bloody civil war. In 1978, Rummenigge recounts, he got caught up in a street battle in Beirut with PLO fighters and killed a number of Palestinians. Ever since, the mere mention of the word, Palestinians, is enough to spark a burning hatred in his eyes; he won’t even speak Yasser Arafat’s name, and instead uses a series of epithets and curses, the most low-key of which even is not fit to print.

In the wake of the street battle, the Palestinians and the Syrian forces, that supported them, put a price on Rummenigge’s head and the danger to his life was palpable. While no longer president, Chamoun remained a central figure in the complex web of Lebanese politics, and he smuggled al-Hajj out to the Christian sector of the city.

The young Rummenigge was appointed initially as Chamoun’s aide, and then went on to serve as head of the former president’s team of bodyguards. He was trained in close-quarters combat and VIP protection techniques by then-Jordanian King Hussein’s personal security guards. On one occasion, he sustained injuries in a car-bomb attack aimed at taking out Chamoun. The assassination attempt would become one of many that Rummenigge would survive. The injuries he sustained left their mark: He needs to get out of his chair every few minutes to straighten his back – a reminder of the piece of shrapnel that pierced his body in one of the attempts to kill him. Most of these attempts resulted in the death of the assassins, or as Rummenigge customarily puts it when describing the elimination of his enemies: “We sent them to their mothers.”

And he sent quite a few people to quite a few mothers.

Meanwhile, throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, Rummenigge became more and more involved with Camille Chamoun, and was exposed, too, to the clandestine ties between Lebanon’s Christians and Israel. “The Chamoun family had absolute faith in Amin and they entrusted him with some of the logistics of the ties with Israel,” says a source who was serving in 504, the Israeli Military Intelligence unit dealing with the requirements of live agent, at the time. “We saw it as an excellent opportunity to get close to this wild man.”

The fact that Rummenigge was sitting slap-bang in the middle of a critical intelligence crossroads, was no fan of the Palestinians to say the least, and was well connected within a torn-apart Lebanon made him a prime candidate for recruitment as an agent for Israel. Unit 504 officials decided to make the move and slowly began using the meetings Rummenigge would come to on behalf of Chamoun to get close to him, until he was recruited.

Rummenigge became an Israeli agent; and at the time, no one – not even al-Hajj himself – could have imagined where the young man from Dahiyeh in the south of Beirut would end up.

Not even one dollar

“Initially I simply told them (the Israelis) what I knew – a piece of gossip from here, a story from there, and some other information we received about the PLO,” Rummenigge says of the beginnings of his ties with Israeli intelligence. “From meeting to meeting, they wanted to know more and more. They would always come to me with a long list of questions and tasks.”

Shortly thereafter, he acquired the nickname that would stick with him throughout the years. The issue of the nickname is an essential component in the recruitment and handling of a source. The idea is to create a divide between the true identity of the source, his name and particulars, and the person who gets to read the material the source provides, all for the sake of guarding his safety and keeping his ties with Israel under wraps. For this very reason, a source may have several nicknames, in keeping with the type of intelligence he provides, the identity of the consumers, or the organization for which he is working on a particular operation.

According to one of Al-Hajj’s handlers early on, “After it was clear that he was collaborating with us, we needed to record him as a source and assign him a nickname. Usually, headquarters (of Unit 504) determines the nicknames, something that’s supposed to be random. But I wanted to do something different this time. I was a big fan of Bayern Munich at the time, as I am today. Back then, supporting a German soccer team wasn’t the done thing. Many of my friends, soccer fans from within the unit, were very angry with me for daring to show such fondness and support for something German.

“So I decided to rub it in a little, and to pay a little respect to the player I admired most – Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, who was the league’s top scorer that year, 1979; I think he scored 25 goals. They were also born in the same year, and in the same month, too, I think – Amin and Rummenigge.

“I requested special permission from headquarters to select the nickname myself, and they agreed. Only then, they asked me what I had chosen. And I said: Rummenigge. They were a little shocked, but accepted it. I told everyone that day at lunch, at the Unit 504 base in Nahariya; and just to annoy them, I said: I hope Rummenigge the agent provides the same amount of intelligence as Rummenigge the footballer scores goals for Bayern.”

And so, with the unusual nickname ascribed to him, al-Hajj relayed intelligence to Israel.

“With time, the information I had was no longer sufficient, and I began deploying an entire network of informants throughout Lebanon,” he recounts. “I’d pay a little money to some young boys and they’d run errands for me based on the tasks the guys from 504 would ask me to carry out.

“We had a special communications arrangement: They’d call from a certain number in Cyprus to a telephone in Camille Chamoun’s office and say they wanted to see me, seemingly to pass on a particular item or message to Camille. When I wanted to get in touch with them, I’d call the number in Cyprus and says it’s Old Fox on the line. Then I’d board a yacht that belonged to the Chamoun family, sail out to sea, and meet there with the 504 people on an Israel Navy missile boat or Dabur (patrol boat).”

At that time, before the 1982 War between Israel and Lebanon, Unit 504 was dealing primarily with PLO activity in Lebanon and collecting data on the organization’s deployment, the size of its forces, the location of its headquarters, and anything else that could be of assistance to Israel.

“They wanted information about the apparatus in the western sector under the command of Abu Jihad, and about his senior commanders in Lebanon” Rummenigge recalls. “They wanted to know the location of the headquarters of Nadim Matraji, Awna al-Hilo, Naim Juma’a from Force 17…”

And from here, al-Hajj goes into a detailed description of the various objectives presented to him by his handlers, making extensive use of the excellent memory for detail with which he is blessed. “At some of the meetings that concerned the location of headquarters and forces,” he says, “they would produce updated aerial photographs, lay them out on a large table on the missile boat, and I’d point out the various sites.”

Over time, the network Rummenigge wove grew and developed. Within Fatah, he had two very senior sources (named Rummenigge 3 and Rummenigge 4) who passed on information to him in return for money. Al-Hajj claims the money came from his own pocket and that he never once asked to be reimbursed or for any payment for his services.

“We were ready to pay him a lot of money,” confirms one of his handlers from Unit 504. “But Rummenigge adamantly refused. On one occasion, during a meeting on an Israel Navy gunboat, he slammed his fist on the table with tremendous force and made a huge scene, saying that if we try one more time to push money on him, he will cease all ties with us. ‘I’m a Lebanese patriot,’ he said to us. ‘And I’m helping you to help us get rid of those fucking dogs (the Palestinians). I don’t need your money and don’t taint the work we are doing here with bribery.'”

According to Rummenigge in our interview, “I helped Israel because I thought it would be the only force that could fight the Palestinians.”

What did you think would happen?

“Very simple: I wanted Israel to enter Lebanon and wipe out the PLO.”

‘He’s a dead man’

At one point, the network Rummenigge set up for Israeli intelligence numbered no fewer than 15 secondary agents. And the information provided by the network served to aid many bombing operations and ground raids carried out against PLO forces in the years leading up to the First Lebanon War.

One of the primary targets about which the network gathered intelligence was Ali Hassan Salameh, whom the Mossad dubbed Burner, in keeping perhaps with Israel’s wish to see him go up in flames. Salameh, one of Arafat’s closest associates and chief of operations of Black September, was the man Israel held chiefly responsible for the massacre of the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics.

“It was clear to me that as far as Israel was concerned, he was a dead man, and as soon as they manage to get to him, they’ll put a bullet in his head,” Rummenigge says. “They wanted information about his office, about his home and about the routes he takes every day between these, and the gym where he used to train, and sometimes the family of his second wife, Miss Universe Georgina Rizk.”

In 1978, the information provided by Rummenigge prompted Caesarea, the Mossad’s special-ops unit, to dispatch its so-called “Warriors” to try to meet up with Salameh at the gym, where they initially thought to assassinate him. Salameh was eventually killed by a car bomb planted by the Mossad in January 1979.

Another principal objective at the time was the pro-Syria as-Sa’iqa faction of the PLO, and its leader, Zuheir Mohsen. Thanks to intelligence relayed by Rummenigge, as well as other sources on Mohsen, Israel knew that Mohsen had left Lebanon and had traveled in early July 1979 to the south of France. On July 25, Mossad assassins shot and killed him. Following the assassination, his faction lost most of its power.

In June 1982, with the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Rummenigge’s network was a principal component of Israel’s intelligence efforts. Rummenigge at the time was running a small vegetable market in Achrafieh, a Christian neighborhood of Beirut; and with the market serving as his cover, surrounded by crates of indigenous cucumbers and juicy oranges from Sidon, he operated his sources. Unit 504 officials, for example, asked him for as much information as possible about the leaders of the Palestinian organizations, in an effort to carry out strikes against them from the air or the ground. “They were interested primarily in Abu Jihad and Abu al-Hol (who was responsible for internal security in the PLO),” Rummenigge says.

During the time leading up to the outbreak of the war, the Mossad also strengthened its ties with another significant force in Lebanon – the Christian Phalange, under the command of the Jumail family. Rummenigge wasn’t too fond of them, but his collaboration continued.

“On a number of occasions, Bashir Jumail came with us on a yacht to meetings in Haifa and puked his guts out all the way from seasickness,” he mockingly relates. “Once, I was present at the start of the meeting between him and Prime Minister Menachem Begin, in Room 214 at the Carlton Nahariya. Joining forces with Bashir and his people was your biggest mistake. They were truly devoid of boundaries, morals or loyalty, and got us all into trouble in the end. Take, for example, what happened when Israel invaded Lebanon – the Phalange entered Sidon and started looting the businesses of Palestinians and raping their women. You shouldn’t have let that happen.”

‘Arrogant show-off’

Towards the end of 1982, with most of the PLO forces out of Beirut and in Tunisia, and the Israel Defense Forces withdrawing in the direction of southern Lebanon, the nature of Israel’s intelligence operations against the Palestinian organizations underwent a major adjustment – and Rummenigge’s life changed significantly too. He left the service of Camille Chamoun and began operating as a private businessman, involved in the transportation of goods by land and by sea throughout the Middle East. Rummenigge transported cars, beverages, cigarettes, and even salt from Israel – and accumulated significant wealth.

There was talk at the time that his import-export network was actually a cover for drug trafficking – allegations that Rummenigge adamantly denies. “I have never dealt in drugs; it’s all a myth. Charges have never been filed against me. No one has ever produced a shred of evidence to support this lie,” he says.

The rumors, of course, didn’t stop Israeli intelligence from continuing to employ Rummenigge, despite the fact he had a tendency to brush off his new supervisor and failed to behave modestly and discreetly, as might have been expected from someone who was collaborating with Israel.

“He put on the whole Lebanese arrogant show-off act,” says a Unit 504 member, “and made sure everyone knew he was filthy rich, driving the fanciest cars, and hanging out with the most beautiful women. Whenever he’d go to a restaurant, Rummenigge would only wait to be told there’s no room – and then he’d shove a few hundred-dollar bills that he’d peel off from a thick wad in his pocket into the hand of the maitre d’. And suddenly, lo and behold, there was room.

“We were really scared to go out to eat with him in public places because he immediately drew so much attention.

“He’d come to the meetings with his handler from 504 at the Rosh HaNnikra base in a new and shiny black Mercedes SEL-500 black. The poor handler would arrive in his trashy Renault 4. The entire scenario story sparked antagonism that Amin didn’t really try to dispel.”

Antagonism or not – Israeli intelligence still had much to do with Rummenigge; and the shipping enterprise he had set up became a wire service of sorts in part too: Rummenigge hired captains and sailors who added eyes and ears in ports to which Israel had no access; and some of Rummenigge’s ships were used by his arch enemies in the PLO to transport equipment and people from place to place. Rummenigge would then relay all this information to his Israeli handlers.

One of the captains who worked for Rummenigge was Samir Asharfi (Rummenigge 13), who turned out to be a particularly useful source of information. “Many terrorists at that time would go for training in Libya and Tunisia,” Rummenigge recounts. “Samir would send us all the details. A number of these boats fell into the hands of the Israel Navy.”

This part of the story ended very badly. The PLO began to suspect Captain Asharfi, and he was abducted in Beirut in August 1985. “They called me from the ship and I realized that Samir had been made,” Rummenigge recalls. “I had someone at the port, who followed the vehicle in which he was taken. He told me they got to the Ein el-Hilweh camp and took him into a certain house, where, as I understood, they were going to interrogate him.

“It was a difficult time. Samir knew a great deal – not only about what he was doing, but also about me and very many other people and our ties with Israel. I realized that if he were to speak, it would lead to the exposure and capture, and surely the death, of many others.”

What did you do?

“I placed an urgent call to 504 and told them what had happened. I gave them the exact coordinates of the location where he was interrogated. A few hours later, the air force dispatched an aircraft that bombed the house and killed everyone, including poor Samir, may Allah have mercy on him. I was very sorry about it. Samir was my good friend – but there was no alternative.”

Hated but feared

Sophisticated and complex operations like these became Rummenigge’s natural environment. The operation in Cyprus that was mentioned at the beginning of the article and in which Rummenigge recruited prostitutes and taxi drivers to report on PLO terrorists returning to Lebanon didn’t end in the bedroom.

At some point, through a firm he owned, Rummenigge purchased a shipping company that had two passenger ships that worked the Larnaca-Beirut line. “I knew that the PLO used these ships to transport people. After taking control of the company, I told them to load one of the two ships, the Maria R, with as many people as they could the next time. I instructed them to give those son-of-a-bitch terrorists blankets and plenty of water and provisions for the journey – anything to make them feel at ease about putting as many as possible on the ship.”

That night in February 6, 1987, around 50 PLO operatives boarded the ship, which set sail in the dead of night with Rummenigge tracking it from afar, from a lookout point on the shore, accompanied by an Israeli intelligence official. Some 50 kilometers off the coast of Beirut, the Maria R was surrounded by Israel Navy vessels – and all those on board were unceremoniously transferred to Unit 504’s underground interrogation facility. The ship’s crew was subsequently released. The PLO members were jailed in Israeli prisons for many years.

This time, too, however, the operation wasn’t an entirely smooth one.

The capture of the Maria R set off alarm bells in the PLO’s offices in Larnaca. Their investigation revealed Rummenigge’s secret ownership of the shipping company. Two PLO assassins tried to kill him outside the hotel at which he was staying in Limassol. Al-Hajj and his wife fled on a cruise ship from Larnaca to Haifa, from where they were then quietly taken to the Tel Aviv Hilton.

A party attended by several of Israel’s intelligence elite and the commander of the Israel Navy was held that same week at a restricted security installation. Everyone was there to pay their respects to the star attraction, the man of the hour – Rummenigge.

But with all due respect to Rummenigge, the fact that his shipping enterprise had been burned didn’t of course stop the wave of PLO terrorists who wanted to return to Lebanon. Israel revealed that the PLO had approached a Cypriot shipping agent by the name of Naoum in an effort to coordinate the smuggling of its people through him. Initially, Shin Bet security service officials tried to recruit Naoum – but to no avail. Rummenigge got word of the matter and asked to be entrusted with the recruitment task.

Naoum was summoned by al-Hajj to a meeting at the Intercontinental Hotel in Athens. To his surprise, Israeli intelligence officials were waiting there for him too. Rummenigge did the talking and made Naoum an offer he couldn’t refuse.

“He came to the meeting with a briefcase,” Rummenigge recounts. “I asked him: ‘What’s that? Where’s your suitcase?’ He replied: ‘I didn’t bring one because I’m not staying. I’m going back to Cyprus in the evening.’ I said: ‘You’ll stay here for as long as these people tell you to stay. And from now on, you give everything you have to these people – otherwise I’ll get you a ticket for a cruise without a ship.’ He knew I was serious and that he wouldn’t want to mess with me.”

According to an intelligence official who was in the know about the operation at the time, “Naoum was always telling me how much he hates Rummenigge, really despises him, but that he’s scared to death of him, and that he has no choice but to obey him.”

Rummenigge confirms the story. “I know he hated me – like many did; but he was afraid. He knew that if he didn’t do what I said, I’d send him to his mother.”

The flow of information from Cyprus resumed. On one occasion, Naoum came through with information that the PLO’s commander of the Beirut sector would be arriving in Lebanon from Cyprus on a small boat. The intelligence came in late, and there were concerns that the navy wouldn’t have enough time to capture the prime target.

A special ops unit that was rushed to Cyprus arranged a “fault” with the PLO commander’s car and he was forced to remain on the island for another 24 hours. The delay gave the navy time to mount an operation to capture the commander, who spent the following years in an Israeli jail and was only released after the signing of the Oslo Accords.

Meanwhile, Rummenigge’s Cypriot network continued to grow, and yielded huge quantities of high-quality intelligence. A relative of one of the network’s members owned an Athenian restaurant frequented by senior PLO officials, and the dining establishment became a hub of extensive activity on behalf of Israeli intelligence.

It emerged later that the son of one of the network’s members was involved in a stormy homosexual affair with a senior Fatah money man. The ensuing pillow talk led to the exposure of the organization’s convoluted and corrupt funding operations. On the advice of Rummenigge, Israeli intelligence officials decided not to tell the network member about his son’s sexual orientation, “because he would have killed him on the spot, no qualms,” Rummenigge says.

And Naoum? What happened to him meanwhile? He served Israeli intelligence loyally until August 1997. Then, during a meeting in Limassol with his Israeli handler, he suffered a heart attack and died.

‘No problem’

Throughout all these years, al-Hajj didn’t budge from his adamant refusal to accept payment from Israel, and wouldn’t even accept money for air tickets. As far as he was concerned, it was a matter of honor. Truth be told, Rummenigge didn’t really need the money. He reaped the benefits of his ties with Israel elsewhere entirely. Following the Maria R affair, al-Hajj became less secretive about his ties with Israel. He built a luxury and ostentatious office block at the border crossing between Israel and Lebanon; and from there, from the heart of an IDF base, he coordinated his booming trade operations. So as not to live too far from his office, Rummenigge leased an entire floor in an apartment building in Nahariya, a cost city, few kilometers south to border, broke down the interior walls, and created a huge living space where he resided with his extended family.

As a cub reporter in 1998, I heard rumors of a strange Lebanese man, boasting a spectacular mustache, who was doing as he pleased in the north of Israel; and I went to Nahariya to meet Rummenigge. From the heart of the huge apartment, surrounded by various means of communication, including a direct link to the naval base in Haifa, Rummenigge would navigate his ships around the Mediterranean, with the room full of fawning companions and beautiful women.

At the time, Rummenigge was in the habit of traveling in a convoy of luxury Mercedes vehicles adorned with diplomatic plates, which he received, according to his version – or stole, according to another – from the Swiss Embassy in Beirut. Late one night, after a few hours during which he refused to say much at all, I got into his car with him. He was going out for a night on the town in Haifa, and I had asked for a ride home.

“Are you ready?” he asked me, his hands gripping the steering wheel of the Mercedes. “Ready for what?” I asked. “For this,” he replied – and slammed his foot down hard on the gas. The Mercedes sped wildly forward. A note to all: The State of Israel has traffic laws; Rummenigge has his own.

Shortly after we passed Acre, a police car with flashing lights appeared suddenly behind us. “No problem,” Rummenigge said with a smile and brought the Mercedes to a screeching halt. The policeman who approached out of the darkness appeared extremely agitated. “Good Evening, Mr. Police,” Rummenigge said with a smile as he lowered his window.

“Ah, it’s you,” the policeman said, clearly disappointed. “Good evening, good evening” – and on his way he went.

“For years, he ran wild in the north like he owned the place,” says a senior Northern District police officer from the period. “But we couldn’t touch him. He had the broad and impenetrable backing of the intelligence community.”

Rummenigge’s relationships with the women in his life were complex affairs. He claims to have been married to no less than 22 women who bore him a total of eight children (one was killed in 1987). One of his wives was a beautiful Lebanese model. Rummenigge convinced her to join him in Israel and the two were involved in a troublesome relationship.

Once, when he was being treated at Ichilov Hospital for complications stemming from one of his injuries, he heard that she was about to return to Lebanon. He lost his cool at the hospital in front of the doctors and his Mosssad handlers, who had shown up just then to visit him, ripped out his IV tubes, and set off on foot with the intention of apprehending his beloved before she escaped. He managed to catch up with her, but she returned to Lebanon in the end.

Rummenigge, however, didn’t remain alone for very long. The same wife returned to Israel, lived in Nahariya and gave Amin a son and a daughter. In 2012, she returned to Lebanon with their daughter, while their son remained her with Amin. She wasn’t the last.

Some of his relatives who remained in Lebanon paid a price for his choice. One of his brothers was arrested by Syrian intelligence officials and died following his interrogation, which probably included severe torture; another brother was thrown to his death from a high floor of a Cairo hotel; “and I have no doubt that it was because of my ties with Israel,” al-Hajj sadly concludes.

All of this took place after Hezbollah had already become a key player in the Lebanon arena. Rummenigge claims that Israel played a significant role in the rise of the terrorist organization.

“The Israelis decided to invest everything in the relationship with the Christians,” he says. “But look, when you they invaded Lebanon, the Shias welcomed the Israeli troops with flowers and rice. Thereafter, you they treated the Shias like dogs. They meddled in their lives and allowed the Christians to meddle in their lives. This gave rise to the platform from which Hezbollah subsequently sprouted.”

Many members of Amin’s family have occupied senior positions in Hezbollah, and many still do including the director of Hezbollah’s legal department, brigade commanders in the organization and one of leaders of Hezbollah’s operational wing. In an opinion piece that appeared in one of the organization’s publications, a group of Rummenigge’s relatives announced his expulsion from the family and his absolute excommunication. He knows he’ll never be able to return to Lebanon.

Like a used rag

At the end of the 1980s, Rummenigge had a falling out with the intelligence community. The backdrop, he says, was an order made for vehicles for Unit 504 and for which he claims he didn’t get the money. Rummenigge took the matter up with the Israeli courts – and failed.

Since then, things for him have gone from bad to worse. First, he was suspected of forging his passport. “I had a Lebanese passport that I’d keep extending for myself, and all with the consent of the guys from 504,” Rummenigge says. “And then what happened? Just because 504 is angry with me now, it’s become illegal?”

Rummenigge was arrested and detained for a few days, but was subsequently released after representatives of the intelligence community came forward to confirm their consent for his actions.

Then, one of his ships was caught in Israel with 3.85 tons of hashish on board. In his defense, al-Hajj claims that corrupt elements in the South Lebanon Army were responsible for loading the hashish onto the ship, and that he was the one who reported the drugs. “They conducted a search of the ship only because of my report,” he says.

To support his claims, Rummenigge points out that no charges were ever filed against him in the case.

Thereafter, he ran into trouble over his purchase of a new fishing vessel, which was confiscated by the Egyptian authorities. Rummenigge went to Egypt to fight the decision, won his case in an Egyptian court, but then discovered that someone had sunk the ship. The Egyptians, for their part, apprehended him and threatened to deport him to Lebanon. Rummenigge took the matter up with Knesset members who had served previously in the intelligence community and knew him from there, and with defense establishment officials; he also placed a tearful call to yours truly with a request for help. Just moments before he was due to be deported to Lebanon, and following intervention on his behalf by a high-ranking member of the intelligence community, he was returned to Israel.

And al-Hajj has been stuck in Israel ever since. He’s here under a temporary residence permit that has expired, without medical insurance, without a livelihood, barely able to support himself, bitter and angry at the whole world. A few months ago, he suffered a stroke from which he barely recovered. And six weeks ago, after the series of conversations we had ahead of the publication of this article, he suffered another stroke, more severe this time – and he was admitted again to hospital, where he still remains today. He’s receiving treatment thanks only to a number of doctors who know him from the past, know of his contribution to the country, and instructed that he be hospitalized despite not having medical insurance.

“It’s a little hard for me to understand why I’m being treated like this, why, after everything I did, everything I provided, all those who were caught thanks to me, they’re tossing me aside like a used rag,” Rummenigge says from his bed.

“People have plenty gripes about Rummenigge, there’s no doubt about that,” says one of his former handlers. “But then again, if he was a saint or a priest or rabbi, he wouldn’t have been able to help us. We look for people just like him. The things he did – and I say this to you based on years of experience – are not the norm; they’re on another level, in a different league, a totally different volume of activity. This man of all people, cannot be left to spin around like a UFO (that) doesn’t exist anywhere. We need to put an end to this shame of treating someone who helped us for so long and saved the lives of so many Israelis in such a way.”

The official response

In response to the claims raised by Amin al-Hajj (Rummenigge), the Prime Minister’s Office, in charge of the Mossad, issued the following statement: “In 1995, Amin al-Hajj was deemed entitled to the services of the Security Assistance Administration. Due to the actions of the individual in question and the fact that he has cut ties with Administration officials, the resolution of his status in Israel could not be completed. Assuming the individual in question submits an approach to us on the matter of resolving his status in Israel, we will again review it.”

As for the quarrel with Military Intelligence’s Unit 504, the IDF Spokesman’s Office stated: “For obvious reasons, and in light of the sensitivity of the entities mentioned in the article, we are unable to elaborate and respond to the heart of the matter. Nevertheless, we must stress that we are unaware of claims against the unit regarding his rehabilitation, and that other claims raised in the past against the unit were rejected by the various legal instances.”

Responding to these statements, Rummenigge says that contrary to the claims made by the Prime Minister’s Office, the process of recognizing him as a rehabilitated agent has even yet to begin, and thus he never stopped it.