Warning signs run deep within Egyptian society

H.A. Hellyer/Al Arabiya

Tuesday, 7 October 2014

‘Knowledge is power.’

-Francis Bacon

It has become something of a cliché, but the saying ‘knowledge is power’ is a very true adage. No less so in the Arab world and the surrounding region – which is probably why so many different governmental authorities and regimes are so keen on controlling access to knowledge. Indeed, they do not stop there – information itself, the barest facts and figures, are also construed with great suspicion. Even data on public opinion itself, which ought to be the most unobtrusive type of information imaginable, can be considered a threat.

It’s easy to see why. Last week, Gallup, the polling company that essentially sets the “gold standard” in the surveying industry, released a set of data relating to Egypt. At this point in Egyptian history, the value of that kind of information is tremendous. The country’s society is polarized – between those who support the current military-backed establishment, and those who are sympathetic to the forces calling for the return of Muslim Brotherhood leader, Mohammad Mursi, to the presidency. The question of who is more popular within the country is a deeply divisive one – and, unsurprisingly, the answer will vary depending on whom you ask.

Since the military ousted the first elected president after the Jan. 25 revolutionary uprising, Egypt has seen a number of polling results released. Tahrir Trends; Gallup; and others – including a few that were remarkably disreputable, and even sectarian. The reality is that the best of polls are not only politically non-partisan, but also done face to face, nationwide – and those are remarkably rare in Egypt. Hence the attention that is given to those reputable polls that do get released regarding Egypt – which provide influence on those in power, and thus power itself is provided.

Gallup’s latest survey is not just powerful in terms of the information it provides – it’s also very easily manipulated. The “war on terror” narrative that so invigorates Egyptian society, and its political elite, at present is in desperate need of being moderated, tempered, and thoroughly reversed. For Egypt to get through this current phase of its post-Mubarak transition with any degree of health, the notion that a security solution is appropriate to all types of dissent needs to be not only discredited, but fundamentally rejected. A poll that reveals that indeed, the current administration, which has been viciously criticized by a variety of human rights organizations inside and outside of Egypt, is quite popular, can easily be abused. The more right-wing elements within the emerging political establishment can, fairly effortlessly, use that sort of information to claim that the population does not actually disagree with a hard security solution to the country’s problems.

Short-sighted and dangerous

Beyond any notion of strategic positioning, however, such a usage of the data would not only be misleading – it would be wrong. The data released last Friday does, indeed, lead to the conclusion that when it was collected, shortly after Sisi’s presidential election, a majority of Egyptians felt the economy was getting better. Moreover, the latest government of Prime Minister Mahleb is the government which more Egyptians have confidence in than any other in the last four years. Supporters of the current administration will likely look at these numbers, and smile triumphantly, figuring that the post-Mursi political dispensation is remarkably well rooted in popular support.

“Knowledge, indeed, is power. But while it can warn, there are also some things it cannot protect against”

That would be an incredibly short-sighted and dangerous assessment, however. The numbers are, actually, rather worrying. Looking at how public opinion has varied over the last few years, the main lesson to be drawn by these numbers is not that the post-Mursi political dispensation has popular support – that should have been obvious since the military ousted Mursi last year. A far more troubling issue is that of high expectations. In the past four years, expectations for governments to succeed in turning things around for more Egyptians citizens have gone up and down, dizzyingly.

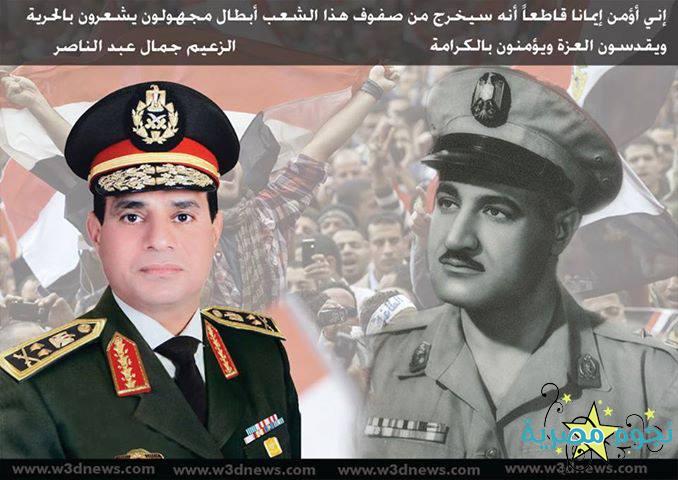

What these numbers show is that, again, Egyptian citizens have very high expectations for the current administration. Hosni Mubarak and Mursi both met their fates after varying forces instrumentalized popular discontent against them. No-one seriously ought to think that Sisi’s administration will meet a similar fate – he has not only sufficient popular support, but the backing of key institutions in the country – but that is not to say that the crashing of expectations come without a cost.

On the contrary, if anything has been clear about the last few years, it’s that the failure to meet the expectations of Egyptian citizens comes with consequences. In 2011, it eventually led to Mubarak becoming a liability, and being removed from office by the military – not the success of the revolution, but certainly an end to his political career. In 2013, Mursi’s inability to build a genuine coalition made him vulnerable to his opponents – and popular dissatisfaction made him a target.

Getting too comfortable

In both cases, however, the disgruntlement of a majority of Egyptian citizens was defused by an organised political act, carried out by the most popular state institution in the country – the military. Expectations for this new administration are high – and if it does not meet those expectations, and there is another wave of popular upheaval, it won’t be like 2011 or 2013. Because in this scenario, there does not seem to be any political force that anyone really trusts anymore. In this scenario, a chaotic bedlam, with no observable political entity, could become a reality, based on purely economic grounds. Knowledge, indeed, is power. But while it can warn, there are also some things it cannot protect against. Egypt’s new rulers should not feel comfortable due to knowing that the majority of the Egyptian population has confidence in their ability to deliver – because with that confidence comes the expectation they actually can deliver. If they do not, then that popular discontent which was temporarily defused in 2011 and 2013 could easily manifest itself again – and possibly in a far more chaotic fashion.