An Anatomy of Sisi’s Liberals

Nervana Mahmoud/Washington Institute

October 31/ 2014

Many self-proclaimed liberals in Egypt supported the military’s intervention in July 2013 that led to President Muhammad Morsi’s ouster. Their stance has baffled many Western observers, who wonder how anyone with liberal values can support an oppressive coup that removed a democratically elected president. There is no easy answer to this question, but an examination of Egypt’s contemporary evolution may explain the state of mind and perplexing behavior of the liberals who have coalesced around Egypt’s new president, Abdul Fattah al-Sisi.

The concept of the Egyptian military as a “liberal force” originated during the rule of Muhammad Ali Pasha, the founder of contemporary Egypt. Historically, themilitary was always run by foreign warriors, known as the Mamluks. They continued to exist under the Ottoman Empire. However, they posed a threat to Muhammad Ali, the ambitious ruler of Egypt. Ali declared independence from the Ottomans, got rid of the Mamluks, and strategically decided to incorporate native Egyptian peasants into the ranks of his modern and professional military force. For Egyptians, the idea that our loyal men are fighting for our country prompted a deep trust in the military as the savior of Egypt that remains to this day.

On the civilian side, although Egypt experienced an enlightenment movement in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was not entirely successful. Not only did it face strong opposition from conservatives, but it was also marred by cowardice and ideological incoherence. For example, prominent nationalists and strong advocates for a modern, independent country opposed feminism. For them, the views of Egyptian feminists such as Qassim Amin regarding women’s rights were unsuitable for Egypt. In other words, they wanted an Egypt free of colonialism, but tolerant of oppressive attitudes toward women. This cherry-picking of modernity was the first step in creating a deformed liberal movement in Egypt.

Furthermore, these liberals failed to support one another in times of crisis. Very few stood by iconic Egyptian writer Taha Hussein after he wrote On Pre-Islamic Poetry, in which he challenged the authenticity of some of the stories in the Quran. Hussein was virtually left alone to defend himself against a barrage of criticism. Although no legal action was taken against him, he lost his position at Cairo University; other liberal intellectuals faced similar experiences later on.

Hussein’s experience taught liberals to embrace a softer approach to publicize their ideas, favoring mediums such as fiction, cinema, and the arts. The aim was to change society’s subconscious rather than conscious behavior, while avoiding confrontation with traditionalists and religious scholars. It worked, but only just. While Egyptians enjoyed their liberal movies, they were not necessarily happy to reciprocate them in real life. The gap between the cinema and ordinary Egyptian life in the 1930s and 1940s, therefore, was very wide.

While liberals focused on forging a progressive Egyptian identity as a pillar of the state, the Muslim Brotherhood aimed to undermine their mission. By claiming to defend Islam from a “liberal assault,” the Muslim Brotherhood succeeded in gaining empathy and sympathy from certain sections of Egyptian society. Although some analysts argue that the Muslim Brotherhood did contribute significantly to Egypt’s overall identity, I believe that Egyptians share only some of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Islamist values. The volatile dynamics of Egypt’s political and social arenas have prevented many Egyptians from reflecting deeply on this unharmonious, perhaps even contradictory, mix of conservatism and liberalism.

The 1952 revolution was a crucial milestone in the liberal-conservative standoff. On the one hand, President Gamal Abdul Nasser needed the liberals to help forge his political ideology that blended elements of classic liberalism with basic Islamic ones. On the other hand, the liberals needed Nasser’s authoritarianism in their battle against the Muslim Brotherhood, as they lacked the intellectual prowess to confront the ills of political Islam. Nasser therefore served as a patron who could help them evade an intellectual confrontation with the Islamists, while subtly fighting the Islamists at the same time.

Nasser’s reign was crucial in marginalizing the Muslim Brotherhood, while allowing a newly engineered identity to dominate Egyptian politics and society. Many Egyptians welcomed this new identity; the liberals embraced the concept of the “liberal military” and it seeped into the nation’s collective psyche. The cinematic productions of the 1950s and 1960s are glaring examples of this glorification of the military and its soldiers.

Unlike Nasser, President Hosni Mubarak drew scant affection from Egyptian liberals. Mubarak had abandoned Nasser’s contract with the liberals as part of his survival strategy. He uprooted many of them from various positions, particularly in the Ministry of Culture, a move that greatly minimized their influence on the younger generations. Moreover, Mubarak reduced the military into a shadowy, albeit rich, institution that was remembered in the context of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War.

Mubarak also allowed the Muslim Brotherhood to empty the liberal core of Egypt’s identity and expand their shadowy, conservative one instead. They were allowed to import the social mores and customs from other Islamic countries into the fabric of Egyptian society. Mubarak nonetheless set a clear directive to the Brothers: they were not to pierce the liberal veneer of the state. But it was finally penetrated after the 2011 uprising and Morsi’s subsequent election, a move that rattled both the liberals and the generals alike.

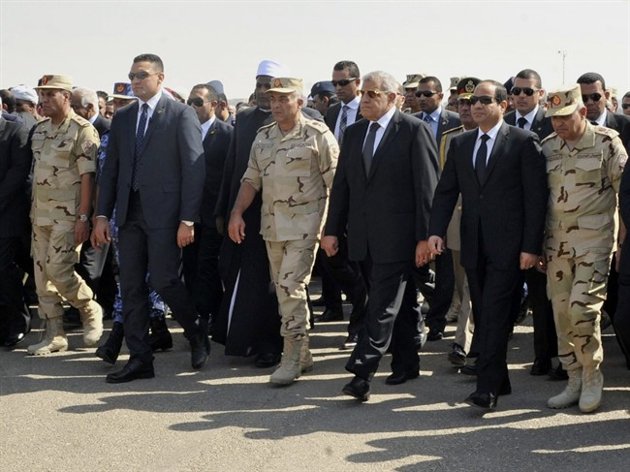

It is hard to identify Egyptian liberals’ true feelings about the military. They probably feel an eclectic mix of genuine respect and trust tied to dystopian thoughts. The marriage between the liberals and the generals grew weak under Mubarak, but was rekindled by Morsi’s overt Islamism. Inadvertently, Morsi made both understand the need to join together to survive. After the 2013 coup, the military succeeded in restoring its image as the patron of Egypt’s classical liberal values, allowing the liberals to defeat the Islamists without exposing the discrepancies in their beliefs.

Sisi’s liberals are the inevitable product of Egypt’s incomplete, contemporary evolution. Their manners, behaviors, and beliefs are stark examples of what has gone wrong in Egypt over the past 150 years. It is true that the military establishment is less conservative and more authentically Egyptian than the Muslim Brotherhood. But to define the military as a liberal force is wrong. There are plenty of ways to explain Sisi’s popularity among the public, but liberalism is certainly not one of them.

**Nervana Mahmoud is a blogger and writer on Middle East issues.