Syriac Epigraphy in Lebanon: Syriac inscriptions and Art on Maronite Churches

د. امين جول اسكندر: النقوش السريانية في لبنان: نقوش سريانية وفنون في الكنائس المارونية

Associations and movements like our Tur Levnon-the Syriac Maronite Union aim to preserve Syriac heritage in Lebanon and to revive the Syriac language. This project can be made achievable by reintroducing Syriac to Christian schools and to the Maronite mass. For this aspiration to become possible, it is necessary to show Maronites what they are losing when they abandon Syriac language and script by replacing them with another language and script.

Why is it fundamental to reintroduce the Syriac language and history in our teaching?

Because today our society ignores everything about its identity, its heritage, culture and spirituality. People have no idea what is being said in Syriac during the Maronite mass. Some Maronites have no idea what language they are listening to. Others think Syriac is being used because it is the language of Jesus Christ. No one suspects this is really something of our past, our literature and our living identity. No one suspects these are the last traces of our identity that need to be saved, valued and revived if we intend to remain as a living people in this part of the world. That is why in our previous researches we first intended to make people aware of their heritage and its existing traces in our contemporary environment. It was necessary to first explain our history and literature, and then expand the study to shed light on the manifestations of our Syriac identity in art and Lebanese architecture (1). In this study we want to go deeper into our past and culture and we will try to express our spirituality and the quality of our relation with the Divine.

How does Syriac culture approach the Divine, the Beyond and the concept of Existence? And what would we – Syriac Maronites – lose when we abandon the Syriac language and Syriac script developed by and for our Syriac way of thinking, philosophy and understanding?

The approach below focuses on the field of Epigraphy. This science concerns inscriptions on hard supports like stone and even rock. The study concentrates on the territory of historical Mount Lebanon, from Qebayet to Jezzine, being the homeland of the Maronites. First, it was necessary to create a repertoire of epigraphs from all over this territory and belonging to all periods because, unfortunately, nothing was ever done in this field regarding Lebanon. Several archaeological campaigns were done and published regarding the rest of the Syriac Fertile Croissant –from Edessa and Tur Abdin, up to Nineveh and Diyarbakir- covering most of Syria-Mesopotamia. These publications started as far back as 1907 with Henri Pognon (2). But the Lebanon of the Maronites never got its share of publications except very exceptional and brief approaches like Mission de Phénicie of Ernest Renan in 1860 (3). The French writer mentioned some Syriac epigraphs he found randomly while searching for Phoenician and Greek inscriptions. Authors like the Jesuits René Mouterde (4), Paul Mouterde (5), the Vicomte Philippe de Tarazi (6) and, later, Salamé-Sarkis (7) -who worked on the garshouné inscriptions of Tripoli – also mentioned only very few Epigraphs in Lebanon. Others like Pierre Chébli (8), Henri Leclercq (9) and Alain Desreumaux (10) chose to repeat in their publications the older discoveries of Ernest Renan.

This general observation proves that a fully new survey and documentation was necessary to support and base our research on. The result was a catalog of a hundred inscriptions (11) from which 36 were chosen to elaborate a theory of the expression of Syriac spirituality around this type of art. The 36 inscriptions selected are interesting because they belong to a complete environment or building. The other examples couldn’t be part of the selection because they were either isolated or seemed amputated from the architecture or ensemble to which they might have belonged. After the catalog was completed and published (12), it was finally possible to start the analysis phase. The observations made during our study were fascinating as they were very unexpected. Facts that could have sounded completely random and thoughtless appeared to be repeated in exact ways in very different places and periods. Coincidence could not explain these similitudes anymore. The elaboration of a certain number of canons and rules was imposing. Two types of configurations are described here to substantiate the idea of this phenomena. The first is about the Saint Bernard prayer, and the second is about the squarish movement.

The Saint Bernard prayer

With the creation of the Maronite College in Rome in 1584, the latinization of the Maronite Church was increased with more and more noticeable influences. One of them was the use of the prayer, or Memorare, of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux to the Virgin Mary. It was somehow modified to be adapted to garshouné, but the meaning remains the same. We read in it:

He who becomes a servant to the Virgin Mary, will never perish.

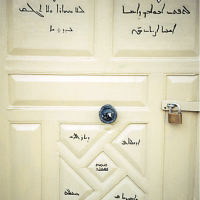

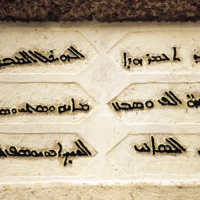

This prayer written in garshouné appears five times between the Metn Mountain and the Jezzine area in Southern Lebanon. We find it in a circular shape at Notre-Dame-du-Pré in Qornet-Hamra from 1703 (13) (fig. 1), Notre-Dame de Machmouché, dated 1732 (fig. 2) and Saint-Maron in Mazraat-Yéshou, dated 1814 (fig. 3):

We encounter it again but in strait lines in Notre-Dame de Tamish, dated 1807 (fig. 4) and Notre-Dame-des-Semences in Kphiphén, dated 1838 (fig. 5). Hence, from the Metn Mountain to the Jezzine area, the example repeats itself five times, three of which respect the same configuration: It is circular and turns around an oculus. Without the corpus provided by our catalog, no one would have ever suspected this circular garshouné inscription of Saint Bernard evolved a continuous code in the Maronite Church.

The squarish movement

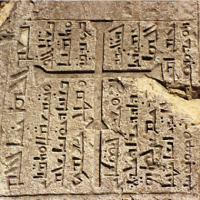

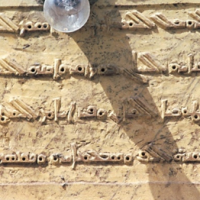

We notice that the gyratory inscriptions inside squares have a particular organization. Instead of turning in respect to a swastika shape, or equal-armed cross, the movement does not obey any sort of equality between the four sides. In fact, the top lines are the longest, using the entire width of the square. The vertical lines to the left as well as the horizontal lines in the bottom, use the 2/3 of the width of the square, and respect therefore the logic of the swastika. But the only space left for the last side (vertical lines to the right) is ½ the width of the square. The whole composition looks like a mistake and as if a lack of planning lead to this forced shrinking of the last lines. But if we consider several examples of squarish movement compositions, we notice they all follow the same rules.

Let us contemplate four examples, of which three are from Lebanon (17th-18th century) and one from Medieval Syria-Mesopotamia: Saint-Shalito in Gosta, dated 1628 (fig. 6), Saint-Antoine-le-Grand in Daraoun, dated 1656 (fig. 7), and Saint-Georges-Martyr in Néemé, dated 1756 (fig. 8) all show the identical logic described above. In Syria-Mesopotamia, the unchanged code is visible again on the Chair of Bennaoui (14) (fig. 9). The similar space organization is respected; nothing is random. It is even possible to say that this lack of balance between the lines is desired by the sculptor to emphasize the direction of the text. He clearly wants to avoid the equality between the lines. He therefore neglected the equal-armed cross composition which was very well known at the time as is shown by many swastika representations on stones and mosaics all over Phoenicia and Syria-Mesopotamia. The huge difference in time and space, is a proof that Maronite sculptors were not working randomly, but rather following a clear set of canons and conscious tradition reflecting their living identity, and going back many centuries in time.

The pyramidal composition

The most characteristic feature in the art of epigraphs appears to be the pyramidal composition “Soyumuto Piramidoyto”. It is represented by the 36 examples selected from the hundred inscriptions of our catalogue because they are part of a complete and coherent set involving architecture, art and inscriptions.

The architectural style typical of Maronite churches is very stark, simple, ascetic and severe. The atmosphere of humility and modesty reigns everywhere. There is very rarely any type of ornamentation or virtuosity of any kind; just as the Mimré of the Syriac Fathers of the Church remain humble and poetic away from Greek theological controversy. The Syriac Maronite tradition is deeply monachal. Its architecture is sometimes harsh or even troglodytic, and its art is reduced to the Crosses. All the life of the Maronites is oriented and focused on the Eucharistic. Saint Ephrem and other Syriac authors wrote in poetry. The Maronite hymns and prayers are chanted, by the clergy and the people. The concept of virtuosity was an alien in the valleys and on the slopes of Lebanon continuously covered with the smoke of incense “bésmé” rising from every cave, every church and every house. The monks, like the people, were peasants harboring the terraces of the mountains.

In this atmosphere of austerity, nothing could disturb the silence of contemplation. The churches were called sanctuaries “Hayklo”. They were sanctuaries for the Eucharist in the communion. They are the house of communion, horizontally between the worshipers and then vertically with Christ-Hosts. The Syriacs call the Eucharist Qurbono and the mass Qurobo. But the Maronites call them both Qurbono and make no difference between the two, because for them, Mass is the Eucharist.

What do we see when we look at a Maronite church that presents an epigraph? Simplicity is always there all over the facade. Then appears the entrance door “Tar‘o” emphasized by its frame consisting in megalithic stones. Above it, sits the epigraph with its simple calligraphy as austere as the architecture and the peasants’ life. There is no place for embellishment and certainly no virtuosity. Somewhere on the facade, under or above the epigraph, rules the cross “Slivo”, and sometimes it is flanked by the two circles representing the sun “Shemsho” and the moon “Sahro”. If we look above, we might find an oculus or a simple opening. And some churches even offer the representation of the Chalice “Koso” and occasionally the Paten “Pénko”. This is all that can be found on the entrance facade of a Maronite Church that has a Syriac epigraph. What is the meaning of each of these elements, what is the message conveyed by their juxtaposition?

… What do we see when we look at a Maronite church that presents an epigraph? Simplicity is always there all over the facade. Then appears the entrance door “Tar‘o” emphasized by its frame consisting in megalithic stones. Above it, sits the epigraph with its simple calligraphy as austere as the architecture and the peasants’ life. There is no place for embellishment and certainly no virtuosity. Somewhere on the facade, under or above the epigraph, rules the cross “Slivo”, and sometimes it is flanked by the two circles representing the sun “Shemsho” and the moon “Sahro”. If we look above, we might find an oculus or a simple opening. And some churches even offer the representation of the Chalice “Koso” and occasionally the Paten “Pénko”. This is all that can be found on the entrance facade of a Maronite Church that has a Syriac epigraph. What is the meaning of each of these elements, what is the message conveyed by their juxtaposition?

The Door “Tar ‘o”

The Door is the entrance to the Qurbono (Mass and Eucharist). This is the way to the horizontal communion that can lead to the vertical one with the Divine. The Door gives access to the heavenly kingdom “Malkuto da Shmayo”. It is the symbol of the gates of heaven “Tar‘é da Shmayo”. What is more revealing than the Maronite hymns and especially these chanted by the monks of Saint-Maron monastery in Annéya, while carrying the coffin of Saint Charbel on that Christmas night of 1898? Making its way through the heavy snow, the funeral procession kept on chanting: « Let your doors open » “nétpathoun tar‘ayk” (15).

If we consider the writings of the Maronite Patriarch, Mor Estéphanos Douayhi, and those on the wooden door of the church of Saint-Eutilios in Kfar-Sgab, we realize the importance of the symbolism of the doors and we understand the reason such big megaliths are used to emphasize them. Patriarch Estéphanos Douayhi wrote concerning this subject that « we mean by the opening of the doors, the pleasure that God finds in our salvation. He also quotes Isaiah to express the importance of their continuous opening:

On signifie également par l’ouverture des portes, le bon plaisir que Dieu trouve dans notre salut et son désir de voir tous les hommes accéder à sa connaissance. C’est pour cela que les portes des églises sont ouvertes au moment de la proclamation des Livres Saints pour que le peuple entende la Parole de Dieu et qu’il accède à la connaissance de la vérité, selon ce qui est dit en Isaïe:

« Tes portes seront toujours ouvertes. Ni le jour ni la nuit, elles ne seront fermées, pour t’amener les richesses des nations et leurs rois pour les conduire. Car la nation et le royaume qui ne te serviront pas périront, et les nations seront exterminées. La gloire du Liban viendra sur toi, avec le cyprès, le platane et le buis, pour embellir le lieu de mon sanctuaire, pour glorifier le lieu où je me tiens ». (16)

This same passage of Isaiah (Is, 60, 11) is inscribed in garshouné on the wood of the door, dated 1882 (fig. 10) of Saint-Eutilios in Kfar-Sgab under the epigraph, dated 1776 (fig. 11) and the chalice. Its presence here is the sign of a conscious act very aware of the symbolism and the meaning of the door.

The Word “Melto”

Above the Door, is the epigraph. Its purity and simplicity are a must. One hundred epigraphs discovered and assembled in our catalogue are here to prove that there is no place for decoration or virtuosity in the calligraphy. This Syriac script inherited the purity and sacred aspect of Hebraic inscriptions. Embellishment is rejected because it distracts from the honesty of the Truth. The Truth is God with no face and no name. It can’t be ornamented nor beautified. It is the Word in itself; it is the Logos “Melto”.

An uninformed visitor would think the inscriptions are very simple and sometimes harsh because of poverty in the Lebanese mountains. He would imagine they couldn’t do any better. Nevertheless, some of the examples we encountered show very complex frames and floral decorations, yet only outside the epigraph, without altering the purity of the inscription. Because the Maronite mentality belongs to the monastic Christianity as opposed to the imperial one. In this monastic world there is no exaggeration in the images, no flaunt wealth. It is a world of contemplation towards the beyond and towards the within. Invention is limited… only exists the Word “L’invention est limitée… seul existe le Verbe » says Pierre Francastel (17).

This respect to the purity of the Word is a direct heritage from the Old Testament. Jewish epigraphs have always been respectful of these values and the inscriptions are free from all sorts of ornamentations. Hebrew manuscripts with illuminations are only the result of Latin and Celtic influences. However, Hebrew inscriptions in the Middle East are found to be simple and with pure shapes. This reflection of the Word has been transmitted to the Christian Syriac tradition.

The fruits of the Eucharist “Piré d’Oukharistia”

If Judaism forbids the image of God, it is because His face has not been revealed. Consequently, any attempt to represent the unseen can only be a falsification of the unknown truth. With Christianity God revealed Himself through Incarnation. The first mystery of Christianity is the Incarnation of the Word “Melto étgasham”. Through His Son, God has revealed His face: “Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9).

From this moment on, figurative representations make their appearance next to the inscriptions. The Word is incarnated and the image becomes tolerated. Christianity expresses the importance of incarnation with all its power and all its meaning. Syriac language has two words to designate the body. “Gushmo” is the physical body, whereas “Pagro” is the biological one. And in their Eucharistic prayer, the Syriacs chose to make use of the word “Pagro”, insisting on the idea of flesh “Besro” and blood “Dmo” of Christ.

Next to the epigraphs and to the crosses, the most dominant figure is the representation of the fruits of the Eucharist: The Host or the Bread of life “Lahmo d Hayé” and the chalice or the wine “Hamro”. They are so clearly visible on churches like Saint-Eutilios of Kfar-Sgab, dated 1776 (fig. 11), and Saint-Shalito of Qotara, dated 1857 (fig. 12). At Notre-Dame-des-Semences in Kphiphén, dated 1838 (fig. 5), this subject of the fruits of Good, or Fruits of Life “Piré d Hayé” is represented with its opposite: the fruits of Evil, signified by the image of the two serpents “Grossé”. Like Saint Ephrem, the great master Saint Jacques of Sarug also insisted on this form of duality embodied by the snakes, when he talked about the fruit of life “Piro d’Hayé” (III 653, 13-14) and the snake “Harmono” that killed Adam (III 653, 15-16) (Note 18).

The Cross “Slivo”

The cross is undoubtedly the most widespread motif on the facades that carry an epigraph. Other than the church’s cross mounted on top of the structure, there is always a second cross carved within the facade and in relation with the inscription.

Once again, at Notre-Dame-des-Semences in Kphiphén (fig. 5), the Cross appears next to the Fruits of Good and Evil. It is represented with diagonals symbolizing the sunlight glowing from it. Because it is light and life, the Christian cross is the instrument of victory of life over death. It is the suffering of Jesus Man and the resurrection of Jesus God. The two stars are here to witness. As demonstrated by Saint Ephrem, the Sun and the Moon “Shemsho w Sahro” represent the divinity and humanity of Christ. All these elements are clearly sculpted on the facade of Notre-Dame-des-Semences in Kphiphén, dated 1838 (fig. 5). The power of the Cross is then revealed explicitly in Notre-Dame de Mayphouq, dated 1904 (fig. 13). We read on its epigraph under the cross: “There is no salvation but by the cross, and no life but through it” “lo pourqono élo ba slivo, w lo hayé élo béh”. Similar inscriptions are found on Syriac Orthodox crosses in the Tur Abdin. In one of them we read: “There is no pride but by the cross of Christ” (19).

The most reveling expression is also the most typical one found on many Syriac crosses in Lebanon and Syria-Mesopotamia. It is very usual in epigraphs as well as in manuscripts. This prayer of protection consists of the Psalm 44,5: “By You we shall wound our enemies, and because of your Name we shall tread upon those who hate us” (20). In Syriac, it appears in two similar forms: “bokh ndaqar labeéldvovayn w bashmokh ndoush lsonayn” or sometimes: “bokh ndaqar labeéldvovayn w métoul shmokh ndoush lsonayn”. We find it in many Churches, and very significantly on the most important Maronite epigraph of Notre-Dame d’Ilige, dated 1276 (fig. 14).

Conclusion

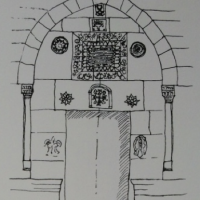

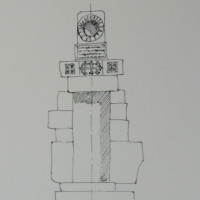

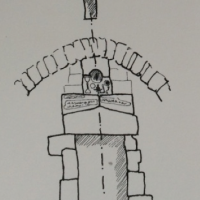

If we consider the entire composition of the facade, while bringing all together the Door, the Epigraph, the symbols of the Eucharist, and the Cross, we notice a vertical axis that organizes all these components. A form of symmetry is revealed as well as a pyramidal effect due to the positioning of the larger elements at the bottom and smaller ones at the top. The base of the pyramid is imposing because of the megaliths shaping the door like at Saint-Joseph of Daraoun, dated 1765 (fig. 15). Sometimes the lintel is over mounted by a second lintel with motifs. Then appear the epigraph, the oculus and the cross in diverse orders according to each church facade. In Epigraphie Syriaque au Liban (21) we mentioned 36 examples of this type of composition. We publish here 6 of them as sketches to provide a visual understanding: Saint-Joseph of Débiyé, dated 1753 (fig. 16), Notre-Dame-des-Champs in Dlebta, dated 1755 (fig. 17), Saint-Joseph of Daraoun, dated 1765 (fig. 18), Saint-Eutilios of Kfar-Sgab, dated 1776 (fig. 19), Saint-Abdon of Maad, dated 1797 (fig. 20), and Notre-Dame-des-Semences in Kphiphén, dated 1838 (fig. 21).

Let us now consider the meaning of each of the features constituting the composition: The door invites us to the liturgy and to the horizontal communion between men. Above it is the purpose of this liturgy that is revealed in its etymology: Leitourgia in Greek derives from leitos (public) and ergon (acheivement). This expresses the importance of the horizontal communion between worshippers. They will accomplish the Qurobo (mass) that is also Qurbono (Eucharist).

Above the door, is the epigraph. The inscription is in Syriac letters even if the language is Garshouné instead of Syriac. The observation is important and confirms that Syriac letters are sacred and are aware of their sacredness. Their purity and lack of ornamentation is a proof of that virtue. The inscription is in that matter, the reflection of the Word.

Then, the images of the Eucharist are inserted into the composition: The Paten, the Chalice, the Host or the oculus. They reveal the purpose of liturgy, but also represent the incarnation of the Word. The image became possible after being forbidden in the Old Testament. The Word is now more than just a body “Gushmo”, it is a biological body “Pagro” made of flesh “Besro”. “I am the bread of life” as we read in John 6:48. Christ is our bread, and He is felt by all our senses.

By evolving from the Word to Incarnation, we enter the mystery of Christianity divulged here by the Christic cycle. This cycle started with the Word as in John 1:1 “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (23) “Breshit itawo Melto…” Then we encounter Incarnation, again as in John 1:14 “The Word became flesh” (24) “W Melto besro hwo”.

After Incarnation, the Christic cycle guides us to Crucifixion. The cross is here to announce sacrifice but not death. Because the cross is life and it is the power of Resurrection. Next to it are the sun, sign of Christ’s humanity “Noshuto” and the moon, sign of His divinity “Alohuto”. In this theological approach chanted by Saint Ephrem, the cycle morphs from Christic to Christological, thus approaching the nature of our Lord.

Resurrection leads to the Ascension of Christ. How is this phenomenon indicated on the facade? There is no inscription nor image designating it. It is actually suggested by the entire composition whose pyramidal shape generates the vertical ascending movement. The Christic cycle is being accomplished by the return of Christ to his Father, to the Word. The church’s facade is revealing the whole cycle by centralizing it on the Mystery of incarnation based on the Word. The Maronite Bishop Simon Atallah, from the Order of the Antonins, elucidates greatly this spectacle and describes it as a descending movement at Christmas, that becomes an ascending movement at Easter. He also adds that at first, God becomes flesh, and then, flesh rises to become Word of life:

« Cet accompagnement ou ce cheminement, conduit par Jésus lui-même, et qui précède la célébration du mystère central du christianisme, la Résurrection, ou mystère de Pâques, est une introduction sérieuse dans le mystère de la Rédemption, mystère de l’illumination et de l’Épiphanie, qui était, à Noël, un mouvement descendant, et maintenant, à Pâques, un mouvement ascendant : le premier mouvement fait que Dieu devienne chair, et le second, que la chair ressuscite et devienne Parole de vie » (24).

In his approach, the bishop insists on the dimension of salvation, visible in every phase of Christ’s life, whether in Incarnation, Passion and Crucifixion, or in Resurrection and Ascension. This dimension adds to the meaning of the pyramidal composition, the concept of Redemption.

Crosses, friezes, cornices, frames, inscriptions and images are assembled to narrate the story of Jesus Salvatore. The composition is read like an icon. It has nothing to do with the art of beauty and visual delectation. Like an icon, it is meant to be read. The entire composition and elements of the Christic cycle are combined and concentrated along the vertical axis and within the pyramidal area. Outside this zone, masonry is left to its total rudeness, austerity and humility. Some stones or rocks are found to be used in their natural shape with no adjustment. The pyramidal composition is meant to be isolated on the facade, concentrating the artistic interventions inside a well defined area. This composition expresses itself in harmony with its message in Utopos (outside any tangible space) and in Uchronos (out of time). These are the characteristics of the icon and those of the Christian image. We might therefore ask ourselves: Isn’t the pyramidal composition on the Maronite facade, the equivalent of the orthodox iconostasis found inside the church?

We are facing a representation of the story of Incarnation and Resurrection, including Christology and Soteriology, in an iconographical display. It is thus significant to see what occurs when Syriac spelling is not used in the epigraph. What are the implications on the meaning and on the message conveyed by the pyramidal composition?

Some Maronite Churches have their epigraphs written in Arabic letters. Their calligraphy is a display of virtuosity in shapes and movements. The letters cover the surface of the stone in every direction showing the skills and talent of the sculptor. Nothing remains from the asceticism of the Syriac script.

The Arabic versions are also longer than the Syriac ones. The numerous praises and literary embellishments burden the text and distract from the heart of the matter. In the form and substance, the inscription is an exhibition of abilities. Richness, virtuosity and pomp replace austerity, simplicity and humility, the attributes of the Word.

The pyramid is still there on the façade, as well as the crosses and the elements of the Eucharist. But the Christic cycle is absent since it has been amputated from the Word that is at the origin of everything. In respect to these observations, it is not overstated to say that Syriac is not just a language, and that language is never just a means of communication that could be replaced by any other medium. Language is the specific expression of a very particular spirituality, special ideals, ethics, understanding of life and its purpose or Raison d’être. It expresses these values related to the civilization and culture that molded it and was molded by it. No other language can replace it without altering the quintessence of the message supposed to be transmitted to forthcoming generations.

Dr Amine-Jules Iskandar is President of Tur Levnon-Syriac Maronite Union. The association Tur Levnon-Syriac Maronite Union is based in Beirut, and aims to preserve, teach and spread the Syriac language, culture and identity.