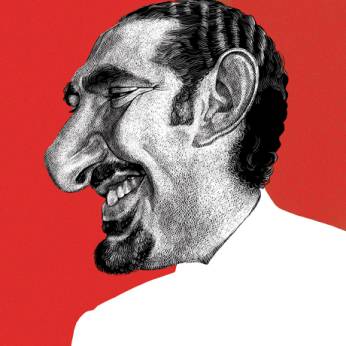

Filling his father’s big shoes

Joseph A. Kechichian/Gulf News/November 04/16

While his more recent Machiavellian steps to back former rival Michel Aoun for presidency illustrate a new acumen for strategising, the Lebanese prime minister’s task is cut out.

As Deputy Oqab Saqr claimed on Thursday evening during his LBC television interview, “Sa’ad Hariri sought to prevent the collapse of the Ta’if Accords, which is the real heritage of Rafiq Hariri,” he for sure went about it the wrong way — backing a leader who actually had a visceral dislike for the agreement that ended the 1975-1990 Civil War and which defines his political legacy.

On Thursday, the newly-elected President of Lebanon, Michel Aoun, nominated Hariri as the Prime Minister to head a new Cabinet, after the Future Movement official secured 112 parliamentary votes. Sa’ad “accepted this commission with gratitude … and the trust of the parliamentary colleagues who honoured” him through this nomination. He chose to ignore the octogenarian’s August 11, 2011 boast to give him a “one-way ticket” out of the country after the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) and Hezbollah ministers withdrew from the Cabinet in January 2011, which prompted a collapse of the government.

In helping elect a former political enemy to the largely symbolic office of the presidency, Sa’ad is, by his own admission, making a huge sacrifice “to save the state from total collapse”. He now faces the gargantuan task of forming a “national unity Cabinet” before November 22, nominally Lebanon’s Independence Day, to benefit from the renewal zeal that most Lebanese expect after what was a two-and-a-half years of political vacuum. Whether he will be able to do so is the heart of the matter, given that the government is not even able to clear out garbage overflowing on streets of Beirut.

That Sa’ad worked in earnest to return to power certainly confirms his innate ability to cope with Lebanon’s shifting political environment, although he surely knows that neither he nor Aoun controls his fate. That honour lies with Hezbollah, the leading group that still refuses to back him, ostensibly because party leaders cannot tolerate the return of the prodigal son. Sa’ad repeated that Hezbollah was behind the suspected assassins of his father and that the party was wrong to be in Syria, fighting on behalf of the Baath regime, which he loathed.

His clear anti-Iranian declarations, which reflected Sa’ad’s strong ties with Saudi Arabia, and which Aoun was dismissive of, highlighted impenetrable contradictions. Moreover, and unlike his assassinated father who knew how to balance conflicting interests on a thin rope, Sa’ad was bound to be at odds with Hezbollah over the latter’s insistence that the ministerial declaration — a proforma utterance that is supposed to act as a guide — include the wooden triptych of the “army-people-resistance” formula to defend the country. Aoun hinted that he could live with the resistance in his lacklustre inaugural speech.

At 46, Sa’ad, who has already served as prime minister once before, will now have to ignore Hezbollah’s claims that it is innocent of the February 14, 2005, assassination of Rafiq. Unlike the father, who was a leading proponent of the departure of Syrian forces from Lebanon, and which occurred in 2005 after the Cedar Revolution broke Damascus’ will-to-power over Lebanon, the young Hariri accepted an official visit to Syria in December 2009, when he met with President Bashar Al Assad.

Ironically, Sa’ad swallowed his pride in a September 6, 2010, interview with the Saudi-owned Al Sharq Al Awsat daily, when he apologised to Syria for having charged it with murdering his father. “Accusing Damascus of the assassination was a mistake,” he said at the time, adding: “The false witnesses misled the investigation and they have caused harm to Syria and Lebanon. [They] … ruined the relationship between the two countries and politicised the assassination.”

Much has changed since then, however, and Sa’ad’s concessions, painful as they were, did not seem to satisfy Al Assad, who secured a full capitulation in January 2011. There was no reason to believe that circumstances have changed ever since, especially in the light of Sa’ad’s more recent pronouncements that backed Syrian opposition figures. In this respect, Sa’ad reflected Gulf Cooperation Council positions — which is crucial, now that he is the Prime Minister.

It remains to be determined whether Sa’ad will learn how to manage some of the most vicious political opponents roaming the planet. Lest he forget, most of those who back him today were lobbing insults just a few weeks ago, even if chameleon-like behaviour meant that everyone was ready to cut lucrative deals with the premier.

Indeed, Sa’ad may have accepted unprincipled conditions as a way to salvage his dwindling reputation among Lebanon’s Sunni community — in the light of Ashraf Rifi’s significant challenge after the June 2016 municipal elections that placed the Minister of Justice in much better light among Lebanon’s Sunnis.

It is also worth noting that while Sa’ad was running the family’s Oger construction firm in Saudi Arabia when his father was murdered, severe financial crises followed, with many employees complaining that they were not paid for months at a time. In June 2016, Sa’ad announced his permanent return to Lebanon, though he continues to spend time in Saudi Arabia — both to look after the shrinking business empire and also to visit his wife, Lama Bashir-Azm (who is of Syrian origin), and their three children.

A business graduate from Georgetown University in Washington DC, Sa’ad will now have to fill his father’s large political shoes, and while his more recent Machiavellian steps to back a former rival for the presidency illustrate a new acumen for strategising, his work is cut out. Of course, there are many in Lebanon who conclude that his intentions to embark on this initiative are honourable and genuine, though most interpret his reconciliation with Aoun as little more than expediency. His greatest challenges ahead are to preserve the political and industrial empires that his father bequeathed upon him and, equally important, the ability to rule alongside his Hezbollah nemesis.

**Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Iffat Al Thunayan: An Arabian Queen, London: Sussex Academic Press, 2015.